“Who should decide what is the common good for a city? Is smart technology an ideal platform where dialogues on the common good can be pursued?”. Dr Suraya Ismail, Director of Research, Khazanah Research Institute, Kuala Lumpur, writes on the complexities of smart urbanism in the context of the Greater Kuala Lumpur conurbation.

_______________________________________________

Why invest in smart cities?

Cities and urban environments are inherently diverse in terms of population densities and economic agglomerations as well as variations in institutional frameworks and governance structures. In this sense problems encountered might follow common themes such as infrastructural (congested roads and flash floods) or socio-economic in nature (social displacements and gentrification). However, the emergence and scale of these problems vary between one city and another.

If we accept the premise that smart city initiatives possess the capabilities of making lives better for its occupants, then ‘smart’ solutions can range from alleviating collective structural ailments such as improving safety and security, better health care and adequate provision of affordable housing; to delivering more ‘efficient’ individual choices of securing parking spaces or reservations for dinner. Some smart solutions are a matter of technological progress, especially in solving the problems of congestion or public safety and security. However, when it comes to delivering positive socio-economic outcomes such as adequate provision of affordable housing or better health care for the poor, it is unclear whether smart city technologies are relevant. This is especially true in some smart cities’ propriety systems that designed universal urban solutions bearing no resemblance to the different realities and problems faced by cities.

What is a good life or ‘the common good’ in a City?

Unfortunately for economists, a city is not made up with homogeneous people. Therefore, the discussion of what a good life might mean to heterogeneous groups, across different cultural and religious beliefs, income distribution- poor, middle-income or the rich, can elicit vastly different responses. There are three inter-related issues in this discussion process; 1) determining which ‘common good’ should be prioritised and pursued; b) implementing the smart technologies for achieving that common good in a timely manner, and c) assuming a city is dynamic and ever-evolving, will there be avenues of debating the priorities of an area once it has been improved?

From Aristotle and Aquinas, a good life is orientated to goods shared with others; the common good of the larger society of which one is part. Even if a good is the same for the individual and the city, the good of the city clearly is a greater and more perfecting one to attain and safeguard. The attainment of the good for one person is a source of satisfaction, yet to secure it for a nation (or cities) is a nobler achievement. It is a virtuous cycle, implying that if this shared vision of a common good is attained, then all inhabitants will be better off, since the ‘small parts’ of society produce the ‘total sum’ of society.

However, according to Rawls, pluralism of the contemporary landscape makes it impossible to envision a common good on which all can agree. Therefore, the intellectual challenge to the common good today is the diversity of visions of the good life. Such a shared vision cannot survive as an intellectual goal if all ideas of the good are acknowledged as partial, incomplete and incompatible.

Who should decide what is the common good for a city? Is smart technology an ideal platform where dialogues on the common good can be pursued?

What is a Dialogue with the Public?

A dialogue with the general public on the common good assumes city inhabitants to be well-versed in the higher purpose of the common good, rather than prioritising their own individual or neighbourhood’s problems. Who will have a better description of the problems we face as a society today? It is assumed that this would comprise mostly of researchers, think tanks and NGOs. Who will have a solution to these problems? Possibly the same group, and presumably adding residents, traders and the local councils. What is the spatial scale of the problem? Does it exist at the neighbourhood, district or city scale?

However, the questions being posed for the adoption of smart platforms currently are as follows: did it translate into a higher return on capital for your city? Which economic strata of society benefitted the most? Have your citizens’ costs of living improved? When smart technology enhanced ‘efficiency’, did it improve liveability? Did it create more spatial inequities? From the outset, these might appear as important questions. However, once we frame the problems faced by society within the dialogue of a common good, questions over the efficacy of delivery might not be as important as determining the right kind of development agenda we would want. Are we doing the right initiatives to begin with? Were cities’ inhabitants given a choice as to whether a smart platform is in their collective or individual interests? Were these issues engaged with in an honest, balanced and open dialogue?

Furthermore, questions posed on outcomes or impacts only after several years of implementation are quite unfair, since cities have longer gestation periods. But more importantly, how do we assess what is good for our city if the technology is not used to create the dialogue, but to just jump straight into the ‘solution’ or ‘future/vision’ that can be dictated by parties with vested interests? These are questions that smart cities advocates must be concerned with.

Greater Kuala Lumpur (KL) conurbation — “Let’s get Smart!”

The historical context and new ideas for cities are equally important in conceiving its development trajectories. Embracing ‘technology’ might just contribute to the creation of new ‘homogenous spaces’ that disrupt the historical continuity of cities, cities that were previously unique, interesting and habitable for the various income strata of society. Smart cities, if created “too quickly”, might create spaces that are alien and inaccessible to some of its inhabitants.

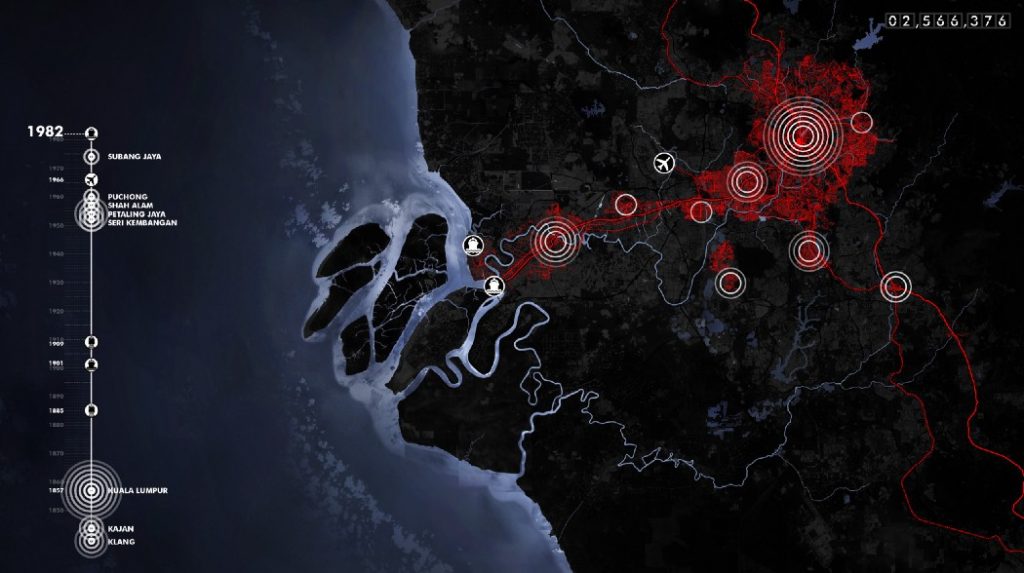

Kuala Lumpur (KL) is the capital city of Malaysia and Putrajaya is the new purpose-built administrative centre. Both Putrajaya and Kuala Lumpur are situated in the Greater KL conurbation, which contributes to approximately 40% of Malaysia’s GDP. Historically under British rule, new routes for tin extraction were developed from Kuala Lumpur to Port Swettenham (renamed Port Klang in 1972) for the purposes of export. For more than a century until the independence of Malaya in 1957, many new settlements and urban centres prospered along this imperial-extraction route. These new centralities created wealth and densified rapidly. Even as late as 1982, urban centres were still concentrated within the general area of this route, as depicted with the red concentric lines in Figure 1: The Urban Centralities along the old trading route.

Putrajaya was not situated on this route, but to the south of KL, and was supported by the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC). The MSC was planned to support both the historic economic route, (KL to the Port Klang) and the new route of KL to Putrajaya, in the hope of creating new clustering of firms and urban centralities (as depicted with the blue lines) in Figure 2: The Multimedia Super Corridor

As a result of this initiative, Putrajaya (along with Cyberjaya) was conceived as a smart city. But the question remains whether engagements were undertaken with the relevant stakeholders — both existing communities as well as the incoming working population.

However, in 2010, the federal government decided to seek feedback on a new vision for Putrajaya. In this exercise, focus group discussions were held. While the outcome was not entirely expected by the government, nevertheless it shows how important it is for government authorities to engage with local stakeholders before embarking on a plan of action. What it also goes to show is that the vision of professional planners may not be seen to be in the best interest of the local populace. This illustrates to a degree the difficulty in determining an acceptable path to urban development even with the assistance of technical professionals. As mentioned earlier, determining the vision of the common good is fraught with difficulties. However, if we accept city making as a deeply fractious, contested process, then a continuing dialogue remains the best way for us to overcome these conflicting priorities. One would have hoped that such exercises also took place before smart solutions were implemented in various municipalities in the Greater KL conurbation.

Conclusion

In the end, the pursuit of the common good, a ‘future metropolis”, is still a realistic social objective. The vision we have for a city derived from continuous dialogues with stakeholders will be invaluable for the city’s sustainability as liveable spaces for a significant proportion of society, rather than just the select few. The appropriate scale to elicit these views — be it at the neighbourhood or city level, and the format in which public discourses of the common good take place, continue to be a tall order. This is a continuous exercise in which each city will need to design and refine as time progresses. Due to the intrinsic time-consuming nature of dialogues and consensus building, the speed of smart solutions can also be tailored to a slower pace, as most cities complain that smart platforms are too ‘quick’ in changing the landscape of their cities.

Cities comprise different sizes and possess cultural and economic heterogeneity. Is it reasonable to hope that adherents of different religious and cultural divides as well as different economic backgrounds can identify aspects of the good life that are common to the lives of all human beings? Yes, it is. With the help of technology to provide avenues and enhance such dialogues, we can make our cities a better reflection of our perpetual pursuit for the common good.

*This blog is based on Dr Ismail’s talk delivered at the 2019 LSE Southeast Asia Forum.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.