“Urban resilience cannot be sustained at the expense of the wider environment. COVID-19 has shown us that many cities are not resilient and are critically unprepared when it comes to climate change”, writes Dr Michelle Ann Miller (Senior Research Fellow at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore)

_______________________________________________

COVID-19 has unsettled existing climate change priorities for urban societies. As global environmental change alters how humans interact with other species, our exposure to pandemics will increase. Cities and urban populations are especially vulnerable to both of these complex planetary problems. Reporting an estimated 90 percent of COVID-19 cases worldwide, cities have become the epicentre of the pandemic.

The same local and global interconnectedness that makes urban populations prone to viral contagion heightens their susceptibility to wider environmental shocks and stressors. Both COVID-19 and climate change are boomerang effects of globalization. As expanding food and energy demands degrade and deplete wider ecologies, urban residents experience these anthropogenic transformations of nature as extreme weather events, air and water pollution, water shortages or floods, heat island effects and other place-based climate change impacts.

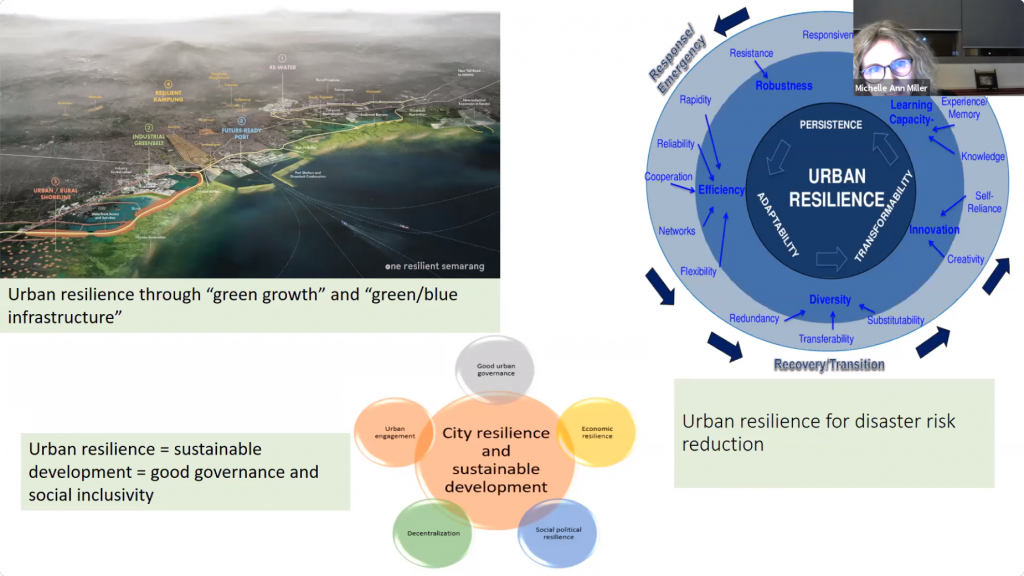

My recent talk as part of the LSE Southeast Asia Week panel on Environmental Resilience and Southeast Asia explored efforts to build urban resilience in Southeast Asia as a governance strategy for dealing with COVID-19 and climate change. Urban resilience refers to the capacity of urban-based ecosystems to withstand, absorb and recover from place and time specific disruptions while building adaptive capacities to cope with future threats and crises. Governments and policy-makers tend to treat urban resilience as an interface that can bring together diverse actors and institutional interests without requiring adherence to a unifying belief system. Yet this malleability also generates confusion about vexing governance questions of what urban resilience means for whom, against what, and to what end?

COVID-19 is redefining urban resilience

COVID-19 is changing how the concept of urban resilience is understood and applied in Southeast Asia. Before the onset of the pandemic, urban resilience was mainly articulated in terms of aspirations for sustainable development within an eco-concerned economy. Notwithstanding the justifiable critiques of green growth, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) saw greening the regional economy as the most viable strategy to address its foremost concern of climate change. With Southeast Asia’s majority urban population comprising around 330 million people as of 2019, building urban climate resilience through the pursuit of Sustainable Development Goals became a regional priority.

This region-wide agenda facilitated the emergence of Southeast Asia’s cities as centres of innovation in urban-based climate change resilience activities focused on balancing economic development with social inclusivity and ecological sustainability. A networked place-making movement sought to integrate large informal economies and burgeoning elderly populations into diverse governance arrangements designed to empower marginal actors as agents of urban resilience. Community-based urban farming, recycling and environmental awareness strategies to build urban resilience through public education gained traction.

While COVID-19 has not brought these urban-based green networks to a complete standstill, restrictions on movement to contain the spread of the pandemic are reconfiguring governance priorities for post-pandemic resilient futures. ASEAN member countries struggling to recover from the pandemic-induced recession are prioritizing economic resilience over environmental sustainability. Climate mitigation strategies are woven into ASEAN’s green recovery plans, but these take a backseat to infrastructural development, accelerated production rates and resilient supply chains aimed at restoring disrupted trade flows while buffering the region against future external risks and uncertainties. For example, Indonesia’s pandemic recovery plans include strengthening its supply chains to enhance food security by expanding its food estate program through the drainage and conversion of millions of hectares of carbon-rich peatlands.

This short-term focus on growth-driven pandemic recovery raises difficult questions about the capacity of Southeast Asia’s urban(ising) societies to build ecological resilience in the longer term. Environmental policing lapsed early in the pandemic when governments across Southeast Asia deployed security forces personnel to urban areas to enforce lockdowns as a means of reducing disease transmission and infection rates. Restricted access to public spaces amidst social distancing measures prevented the physical mobilization of urban-based environmental activism. Digital environmental activism quickly moved into this void, but it could not replace on-site monitoring or place-based conservation activities.

Governments in resource-rich, developing countries of Southeast Asia have exploited this reduced public oversight to roll back environmental regulations in favour of unsustainable development agendas that confer considerable power to big businesses. Pandemic recovery stimulus packages tend to support profitable but polluting industries while weakening the requirements for environmental impact assessments. The rush to return to business-as-usual has seen heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions exceed pre-pandemic levels since the easing of lockdown measures. These levels are now at their highest in 3 million years. Southeast Asia’s global warming reduction targets – which were inadequate before COVID-19 – have experienced additional pandemic-induced delays in the region’s transition to renewable energy and by its continued provision of three of the world’s largest coal pipelines.

The effect of global warming on rising sea levels will severely impact Southeast Asia’s dense urban populations in coastal and riparian areas. Within 30 years, an estimated 31 million people in Vietnam, 23 million in Indonesia and 12 million residents in Thailand are expected to live below-average annual flood elevation levels. Spatial and social inequalities will increase alongside these environmental transformations as more people lose their homes, livelihoods and access to public services. Fractured and divided societies find it difficult to cooperatively engage in collective politics of environmental action that are necessary to build resilience to future disasters. According to the United Nations, inequalities in wealth, access to technologies and basic services within and between the countries of Southeast Asia currently pose the greatest obstacle to recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

Resilience beyond buzzwords

Optimistic predictions for post-COVID-19 urban futures direct attention toward the high concentration of human resources in cities relative to rural areas. This logic holds that cities are rich repositories of knowledge, technologies, capital and spaces for creative exchange that afford opportunities to reimagine more socially resilient and ecologically sustainable ways of life. In Southeast Asia, clean and green plans are already underway to design post-pandemic cities with leafy public spaces, more efficient and inclusive public services, digitally enhanced shopping malls to facilitate social distancing and decongested (online) education and work cultures.

This inward-looking and gentrified vision of urban resilience is at odds with the region-wide inequalities in access to technologies, education and health systems that have been exposed and exacerbated by COVID-19. The International Monetary Fund’s multispeed economic regional outlook suggests that growth-driven pandemic recovery models will further widen rather than reduce the wealth gap to expand existing spaces of socio-economic exclusion while creating new forms of precarity. Ironically, amidst these developments, the language of inclusive resilience that is favoured by the World Bank and the United Nations has been increasingly deployed to obtain public legitimacy for the full spectrum of urban resilience agendas.

Inclusive resilience is a slippery term, which, like urban resilience, goes back to difficult governance questions of who, or what, is included, and why? When, where, and to what degree, is inclusion written into the planning, management and/or implementation of urban resilience programs? Answers to these important questions can, and often do, mean the difference between more or less ecologically and socially sustainable urban pathways. We see how urban resilience deteriorates when development agendas fail to include sustainability measures to promote rejuvenation of the biosphere. For instance, urban demands for agricultural commodities that involve draining naturally saturated peatlands create dry season hotspots, increasing the risk of biomass fires that choke cities across Southeast Asia in transboundary air pollution.

Urban resilience cannot be sustained at the expense of the wider environment. COVID-19 has shown us that many cities are not resilient and are critically unprepared when it comes to climate change. Unless urban resilience is directly linked to environmental outcomes then boomerang effects like the spread of infectious diseases and transboundary pollution are likely to increase in frequency and severity.

Alternatively, the current crisis could inform our responses to future environmental disruptions. It has never been more important to develop resilience as a long-term strategy for coping with biophysical shocks. To this end, COVID-19 contains valuable lessons about building urban resilience by strengthening institutions to promote more socially inclusive forms of resource distribution that have been found to lead to improvements in environmental quality.

* This post is based on Dr Michelle Ann Miller’s roundtable intervention delivered on 30th October 2020 as part of SEAC Southeast Asia Week 2020. You can access a recording of the “Environmental Resilience and Southeast Asia” roundtable here.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.