“The tragedy of the Filipino is an international one. Whether you are dying abroad from caring for the sick, experiencing loss of income, or being killed or assaulted in the streets for breaking lockdown rules at home, for many Filipinos globally, the present is dire and the future deeply uncertain, especially for Filipino healthcare professionals.”, writes Francesca Humi, a fundraising and project development officer, Kanlungan Filipino Consortium.

_______________________________________________

In the wake of COVID-19, academics and researchers in the fields of human geography, urbanisation, migration, and development have been keen to highlight the ramifications of the pandemic for the movement of people across borders: ranging from the impact lockdowns at the national scale will have on international tourism to the geographies on grief, intimacy, and loss – economic, social, and personal (Haywood, 2020; Maddrell, 2020; Walsh, 2020). Initial publications have also looked at the implications of the pandemic onto global remittance flows and on the transborder experiences of law during the pandemic (Abel and Gietel-Basten, 2020; Tedeschi, 2020). These pieces of preliminary research and commentary highlight the inherent international and globalised nature of human geography in the 21st century.

The experience of one group, however, has of yet not been studied in a “post-COVID” lens, despite it being a poignant symbol of the impact the pandemic has had on the most vulnerable, those at the frontlines, and those whose existence is inherently diasporic and fragmented – in short, those whose lives are at the intersections of all the things most impacted on by the health and economic crisis. This is, of course, the Filipino globalised community.

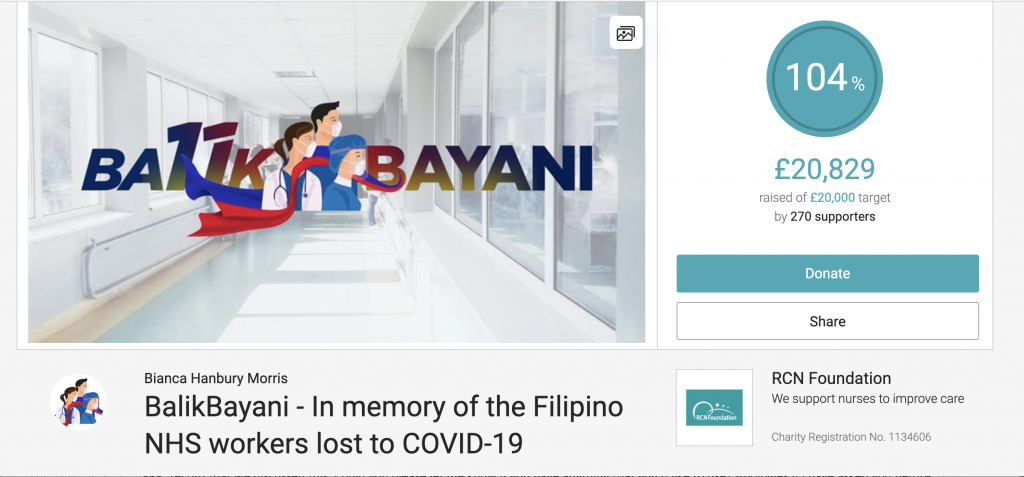

Figure 1: BalikBayani fundraiser to support the families of Filipino NHS staff lost to COVID-19. Justgiving.

The Filipino global nation

Over 10 million Filipinos live abroad, either permanently, regularly, or “irregularly,” according to the Office of the President’s Commission on Filipinos Overseas – representing up about 10% of the country’s total population – without counting the second, third, or even fourth generation Filipinos living across the globe.

Like in many other previously colonised countries, migration flows from the Philippines are shaped by experiences of colonialism, as Parreñas (2001: 10) notes:

United States colonialism in the Philippines resulted not only in a migration flow to the United States but also in a labour diaspora that far transcends this country in geographic scope. The economic turmoil caused by United States colonialism and the subsequent presence of institutions such as the World Bank in the Philippines has led to a migration flow the world over.

Coupled with this, the US implemented a medical training programme in the Philippines specifically designed to bring Filipino nurses to the US, instead of them staying in the Philippines (Choy, 2003: 5). Now, in the US, Filipinos make up three-quarters of all foreign nurse graduates (Choy, 2003: 2).

The Filipino experience can be taken as representative of a fragile globalised system relying on the mobile and docile labour of migrants, both for their work in their destination country and “back home” for their remittances and the opportunities and stability they provide. Fates of both economies are tied by their labour, as Parreñas (2001: 11) again points out:

The contemporary outmigration of Filipinas and their entrance into domestic work is a product of globalization; it is patterned under the role of the Philippines as an export-based economy in globalization, and it is embedded in the specific historical phase of global restructuring.

The Filipino nation becomes disconnected due to physical boundaries and political borders – and now a global pandemic – but connected through an imagined global community, to borrow Benedict Anderson’s concept of the nation, through their shared occupations and similar socio-economic status (Parreñas, 2001: 12). As academics from various fields have noted, this is an archipelagic experience – in virtue of its geography and diaspora, shifting the focus from the national level to a more dispersed and fragmented transnational one, but still connected through an imagined bond (David, 2018: 335; McKay, 2016); Tudor, 2017: 21).

In contrast to the scarcity in initial academic writing on the impact of Covid-19 on the Filipino global community, international media has put a spotlight on how the community has fared during the pandemic. In April, Piers Morgan, the British TV presenter, paid tribute to the contributions of Filipino nurses to the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) on his daily programme, “Good Morning Britain.” Reading out the names of Filipinos working for the NHS across the country, he then saluted the “amazing number of Filipinos [who] work in our NHS.” He continued, “these are the immigrants currently saving peoples’ lives, […] so thank you to all the Filipinos who are here doing all of this amazing work.” This shout-out on Britain’s self-proclaimed “most talked about breakfast television show” was widely shared among the Filipino community on social media and through email chains. My Filipino family members and friends on Facebook gushed over the tribute, feeling the significant labour and sacrifice of our workers in the NHS was finally being acknowledged in the mainstream. But behind this heart-warming tribute lies a more complex and tragic reality for Filipino healthcare workers and their families back home.

‘It’s worth bearing in mind when we talk about immigrants in this country, these are the immigrants currently saving people's lives. Coming here and actually enriching our country and doing an amazing job’ – @piersmorgan pic.twitter.com/dAYcH9t095

— Good Morning Britain (@GMB) April 7, 2020

The failure of two “hero” narratives

While the global economy’s exploitation of Filipino labour has already been pointed out – (in)famously dubbed as “Servants of Globalisation” or described as forming an “Empire of Care,” the current health, social and economic crises caused by COVID-19 have shed light on the magnitude of the West’s dependency on this labour (Choy, 2003; Parreñas, 2001). However, this ubiquity, even in key sectors like healthcare, has yet to translate into material and economic security.

Figure 2: Poster advertising COVID-19 safety measures in Makati, Metro Manila, March 2020. Courtesy of Kathleen Guytengco.

In the Philippines, in a controversial decision, the government halted the deployment of healthcare workers abroad, while asking them to “volunteer” at home for PHP 500 a day (about US$10). These doctors, nurses, and other medical technicians include those who had signed contracts to return to work abroad when the ban was announced. Although the ban was later partially lifted in mid-April, the government’s decision to call on “healthcare warriors” to save the country on the brink of sanitary disaster illustrates the reliance on workers’ willingness to sacrifice their own health and safety for the benefit of society.

In the UK, nearly 40 Filipino NHS workers have already died after contracting COVID-19. Research from HSJ found that Filipinos are the single largest nationality to die from Covid-19: “Filipino staff remain prominent amongst reported deaths, accounting for as many more deaths as the next five countries combined. Filipino nurses comprise 3.8 per cent of the nursing workforce but represented 22 per cent of NHS nurse deaths.” One Facebook post shared thousands of times mourned the loss of Dondee Zuelto, a nurse at Hammersmith Hospital in southwest London, who “passed away on his own, at his flat while self-isolating with mild symptoms after being exposed to a Covid19 patient.”

Online tributes and memorials like Dondee’s will continue to surface on social media, as nearly 20,000 Filipinos work for the NHS, according to research from the House of Commons. Their numbers are third only to British and Indian workers in the NHS. Filipino participation in the British healthcare system is linked to the country’s long history of migration of Filipino workers. The 1990s introduced the first major wave of Filipino nurses and other high-skilled workers migrating abroad, which was facilitated by Philippine government programmes and its own governmental body, the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (Choy, 2003: 1).

The Filipino healthcare worker is at the intersection of two separate – but now overlapping – narratives casting them as heroes. NHS workers have been hailed by the public as heroes whom we applaud from our windows. In the Philippines, for years, the push to work abroad has been bolstered by popular narratives of the OFW as a “modern-day hero,” who endures tremendous hardship to form the backbone of the Philippines’ economy – representing about 10% of the country’s gross domestic product in 2019, according to the World Bank. These remittances represent education, material stability, and better opportunities for families at home. As the memorial to Dondee points out, “[h]e was the breadwinner of his family back home and helping 3 of his nieces/nephews to college.”

Thus, when a Filipino healthcare worker dies from Covid-19 whilst working in the NHS, we grieve the life lost, but we also grieve for their families back home: their loss of stable income and a better future. Workers like Dondee may have been attributed to the status of hero, both in the Philippines and in the NHS, but it will not provide him or his family a changed material reality or security. Being an NHS hero has not translated into sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) or indefinite leave to remain, or even citizenship, for non-British NHS workers. Nor has it translated into adequate protection from the Philippine government. This has left civil-society organisations and charities, such as Kanlungan Filipino Consortium in London, to fill in these gaps in welfare provision.

Figure 3: A woman with groceries and supplies delivered by volunteers in England, April 2020. Courtesy of Kanlungan Filipino Consortium.

Figure 4: Posters appealing for donations and volunteers for a COVID-19 Filipino community outreach project in a shop window in London, April 2020. Courtesy of Kanlungan Filipino Consortium.

This situation exposes the failure and emptiness of these two narratives. Clapping for the NHS and celebrating Filipino workers for their contributions and sacrifices may make them heroes, but so far this has not heralded any transformation to the livelihoods of these essential workers or their families.

For Filipinos still at home, the crisis shows the need to fundamentally question the hero narrative surrounding OFWs. Of course, the hardship faced by Filipinos abroad must be recognised and appreciated, but a new narrative must be forged, one of willing immigration based in autonomy and agency. As Cielito Caneja (2020: 2), a Filipino Respiratory Advanced Nurse Practitioner & Research Nurse working in West London shared in a recent article, “Please do not call me a hero. […] I am a nurse delivering my oath and this is what we do, day in and day out. Long before the pandemic.”

Uncertain post-COVID futures

The tragedy of the Filipino is an international one. Whether you are dying abroad from caring for the sick, experiencing loss of income, or being killed or assaulted in the streets for breaking lockdown rules at home, for many Filipinos globally, the present is dire and the future deeply uncertain, especially for Filipino healthcare professionals.

Figure 5: Protestors at the “Grand Mañanita” protest on 12 June, demanding mass testing for COVID-19 and the junking of the controversial new Anti-Terrorist Bill in on University Avenue in Quezon City, Metro Manila, June 2020. Courtesy of Andrew Alub.

Figure 6: A jeepney driver asking for change along CP Garcia Avenue, his placard reads: “Ma’am, Sir, a little bit of help please for jeepney drivers. We’re hungry” in Quezon City, Metro Manila, July 2020. Courtesy of Andrew Alub.

The COVID-19 pandemic calls for studies on the global migrant community of the Philippines and on countries with similarly archipelagic experiences to be re-evaluated. Much like the climate emergency, the long-term disruptive impact of the pandemic requires a reassessment of how we think of global migration, healthcare and welfare regimes, and the further fragmentation of imagined global communities.

The health, social, and economic crises generated by the pandemic further demonstrate the precarious position of both nation-states and migrant workers caused by global capitalism. Nation-states face near collapse of welfare services without the constant supply of migrant workers, whilst the migrant worker is caught in-between states – their destination-location and home, with neither nation-state able to properly support or protect them. On a macro-scale, the current crisis is a call for a renewed emphasis on the need for transnational, transborder, and archipelagic analyses in the fields of migration, urbanisation, political science, human geography, or gender studies – to name a few. On a more urgent, micro, and human scale, we must ask ourselves, as Cielito, the Filipino nurse in London, humbly asks, “who cares for the carers?” (Caneja, 2020: 3).

Figure 7: Staff at the restaurant Sarah’s at the University of the Philippines Diliman campus in Quezon City, Metro Manila, August 2020. Courtesy of Andrew Alub.

References

Abel, G. J. and Gietel-Basten, S., 2020. International remittance flows and the economic and social consequences of COVID-19. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 0308518X20931111.

Caneja, C. (2020) ‘The Coronavirus Collective: Who cares for the carers?’ Sushruta J Health Policy & Opinion, 13 (3); epub 20.07.2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.38192/13.3.11

Choy, C. C. (2003). Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press

David, E. (2018). ‘Transgender Archipelagos.’ TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 5 (3), p. 335.

Haywood, K.M., 2020. A post-COVID future: tourism community re-imagined and enabled. Tourism Geographies, 0 (0), 1–11.

Maddrell, A., 2020. Bereavement, grief, and consolation: Emotional-affective geographies of loss during COVID-19. Dialogues in Human Geography, 2043820620934947.

McKay, D. (2016). An Archipelago of Care: Filipino Migrants and Global Networks. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Parreñas R. S. (2001). Servants of Globalization: Women, Migration and Domestic Work. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Tudor, A. (2017). ‘Dimensions of Transnationalism.’ Feminist Review, 117, p. 21.

Tedeschi, M., 2020. The body and the law across borders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dialogues in Human Geography, 2043820620934234.

Walsh, K., 2020. A response from home: Intimate subjectivities and (im)mobilities during Covid-19. Dialogues in Human Geography, 2043820620937607.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.