“After Indonesia initiated a form of stay-home policy in early 2020, children were expected to do all of their learning online. This was a significant problem for many in Indonesia because not only is the internet unreliable, but there are frequent power outages.”, writes Dr Najmah Usman, a lecturer in the Public Health Faculty of Sriwijaya University, South Sumatra, Indonesia and Dr Sharyn Graham Davies, an Associate Professor of Indonesian Studies and Director of the Monash Herb Feith Indonesian Engagement Centre.

_______________________________________________

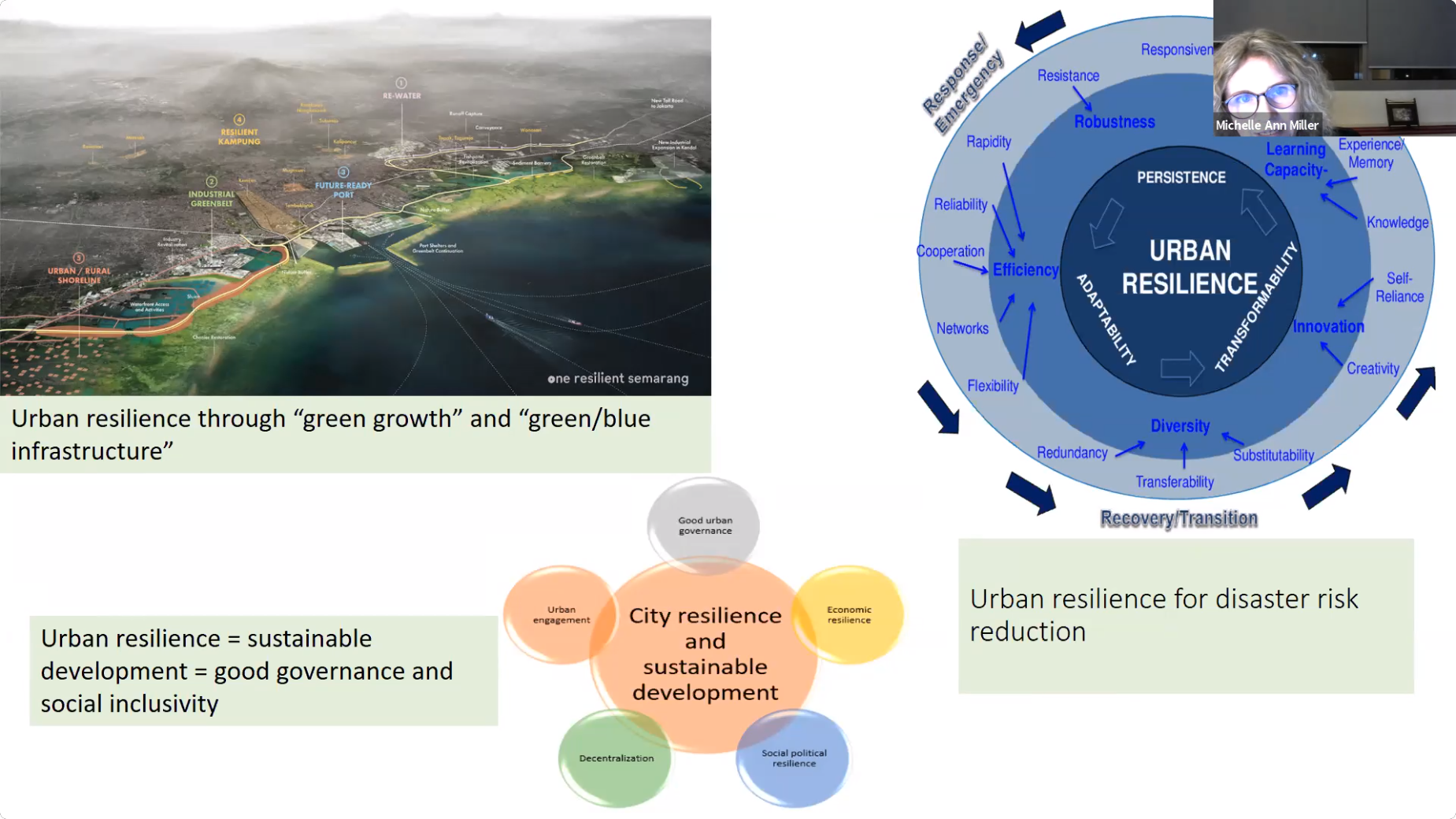

In May 2020, Indonesian President Joko Widodo informed citizens they must learn to coexist with Covid-19, and while health guidelines should be followed, priority must be given to driving economic productivity (Adjie, 2020). While other countries argued the best economic response to Covid-19 is a health response (Long et al), the Indonesian government, for reasons including capacity, provided a largely hands-off health approach. To fill this health response void, grass-root initiatives took on the burden of supporting local communities. In this blog we examine how working together at the grass-roots level enables communities to support each other in their efforts to mitigate the impact of Covid-19.

We share three stories of communities working together. First, we tell of how a group of mothers came together to learn about Covid-19 so they could better safeguard the health of their children. Second, we tell of how a group of university students came together to share Covid-19 health information on Instagram and online news to improve Covid-19 health literacy. Third, we tell of how a group of epidemiologists came together to design a predictive modelling scale to help people understand the seriousness of Covid-19 case numbers. Insights gained from these stories will be useful for government policy makers and other stakeholders in supporting Covid-19 mitigation efforts.

The Indonesian government has rightly been criticised for its lack-lustre response to Covid-19. At best, the response has been negligent. At worst, it has been deliberately misleading. But as is often the case, when a government fails to react, grass-roots organisations step in to fill the void. By supporting their communities in meaningful, if small-scale, ways grass-roots initiatives restore hope in humanity’s kindness and care for each other.

In this blog, we share grass-roots initiatives that have stepped in where national and local governments have failed. In sharing these stories, we hope to advance Southeast Asia research and offer insights capable of informing officials and policy makers in governments and stakeholders in business and civil society, regarding the key issues and challenges in relation to Covid-19 in Indonesia. In particular, we hope readers will find this piece useful not only because it offers insights into different grass-roots initiatives, but also because the area of focus is Palembang, the capital city of South Sumatra, a little considered area in Indonesia’s response to Covid-19. But, it is precisely these smaller, out-of-the-way places, which can be instructive in inspiring beneficial and appropriate Covid-19 responses.

Covid-19 in Indonesia

Statistics are incredibly unreliable in Indonesia in relation to Covid-19. Few tests are performed, and the numbers of reported cases are likely far lower than actual cases. As of October 2020, there are around 316 000 confirmed cases in Indonesia (Worldometer, 2020). Given that Indonesia’s population, 267 million, is four-fifths of the US’s 328 million, and that Indonesia, with much poorer standards of healthcare provision, has reported only 11,000 COVID-19-related deaths while the US has reported 211,000, it is possible that Indonesia’s actual COVID-19-related death toll might be far worse than reported, perhaps even by a factor of ten.

Empowering communities

After Indonesia initiated a form of stay-home policy in early 2020, children were expected to do all of their learning online. This was a significant problem for many in Indonesia because not only is the internet unreliable, but there are frequent power outages. Moreover, few children own a device suitable for home-schooling. Given limited home-schooling options, many children spent their home-time playing with each other outside. Masks were non-existent and despite government guidelines to social distance, children did not heed this, nor did parents understand the importance of such measures.

Noticing the lack of Covid-19 awareness amongst children and their parents, Najmah, one of the authors of this blog, organised a village meeting in April 2020. This meeting brought together mothers, teachers, community leaders and colleagues and alumni from the Faculty of Public Health Faculty at the University of Sriwijaya. At this meeting, a call was put out asking for donations of money, masks, and soap. The response received was overwhelming, showing that a community can and does rally together to help each other.

A further result of this initial meeting was a program dedicated to raising awareness about Covid-19 amongst children. The program was called Penyuluhan Keliling Anak (Pangling, Children’s Mobile Counselling Service). This new program was one of a number that came under the Smart Village program (Kampung Pandai 13 Ulu). In order to run this program, Najmah ran a series of workshops between April and July 2020 educating ten mothers from a small village (Figure 1 and 2). These mothers then helped raise awareness in their communities so that children understood the importance of following Covid-19 health protocols. In their volunteer capacity, these mothers gave out over 1000 masks, 500 bars of soap, and educated over 200 children aged 5-12 through weekly activities such as playing sports.

Figure 1: Raising awareness of Covid-19 through kids’ sport, Palembang, South Sumatra. Mardiana, published with permission.

Figure 2: Smart Kampung 13 Ulu is a top 21 innovation for public services for Covid-19. Sripoku.com

A specific part of this coming together was giving mothers the information they needed to better protect their children. Part of the problem in Indonesia regarding Covid-19 is that senior government ministers have shared harmful advice. For instance, a minister said that wearing a eucalyptus necklace would prevent someone contracting Covid-19. Worse, a minister in the Ministry of Health made the controversial statement that

we are not afraid of Diphtheria so of course we are not afraid of Covid-19 … the flu is more dangerous than Covid-19 … masks are only for sick people.

To counter this misinformation, through informal community meetings, Najmah shared with people the benefit of wearing a mask, washing hands, and maintaining social distance. Once people understood the reason for this, not only did parents follow these recommendations, but children encouraged their parents to do so too (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Mask donation from Pokentik South SumatraNote: Mardiana, printed with permission

Our first learning useful for policy makers and other stakeholders is that with a little support and encouragement, local communities can effectively mitigate Covid-19.

Our second learning useful for policy makers and other stakeholders, is that providing information in local languages, through trusted members of that community, is an effective way of enabling people to understand and follow health protocols.

University students and social media

An under-utilised resource in Indonesia’s response to Covid-19 has been university students. Educated and with access to online platforms, university students can assist with mitigating Covid-19. In helping communities understand the importance of wearing masks and social distancing, a group of university students under Najmah’s mentorship, came together to develop and disseminate online material that could be easily understood by people with low health literacy.

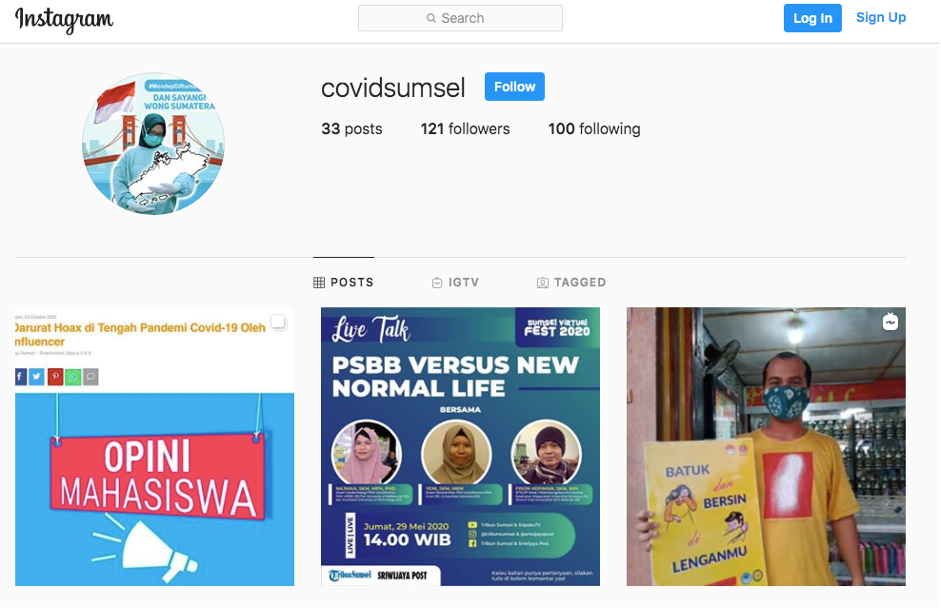

During June 2020, a group of 100 students in the Faculty of Public Health at Sriwijaya University, studying the course The Epidemiology of Reproductive Health, developed 15 short videos about Covid-19 prevention (Figure 4). The students then shared these videos on various social media platforms such as Instagram, WhatsApp, and Facebook. Some of these videos were shared by over 50 students and, within the first week, some had up to 20,000 views. For their efforts, the students were awarded a mark for the subject.

Figure 4: The power of sharing visual outcomes through social media and efforts to increase health literacy related to Covid-19 (Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/covidsumsel/). Copyright Instagram

During October 2020, another group of 30 students in the same Faculty, who were enrolled in the course Social Epidemiology, wrote short articles that were published by a local online news outlet Laju Sumsel. Within a week, each of the opinion articles had been read by over 400 readers. This outreach confirms research by Daniel et al (2013) and Moorhead et al (2013) that social media is a powerful tool for sharing health information, enhancing the accessibility of information, and providing real examples that can influence health policy and public health programmes

Our third learning, then, that is useful for policy makers and other stakeholders, is that including university students in a Covid-19 online response is beneficial in communicating information to communities.

Predictive modelling

A team of researchers at Sriwijaya University, led by Najmah and one of Najmah’s colleagues named Yeni, got together to develop a predictive modelling protocol to show how case numbers of Covid-19 would grow if health imperatives were not followed. This predictive modelling tool was useful because Covid-19 cases are underreported. In addition, within discrepancies in health access to Covid-19 testing between provinces, particularly outside the main island of Java, there is a need for an epidemiological model in each province in Indonesia, including South Sumatra.

To disseminate this model, Najmah engaged with her peers from Alumni of Public Health Faculty (Instagram: to work together and write an opinion piece in local online news, explaining our modelling through online television to provide this information with local languages. Within a day, over 2,000 viewers had watched the live talk. The modelling framework was also published in the ASEAN Journal of Community Engagement.

The model was developed to predict un-reported Covid-19 cases. On this basis, requests were made for the provision of more hospital beds and ventilator. The model also showed the likely high numbers which would be used to make society more vigilant around the threat of Covid-19. The model also measured the lack of testing in provinces outside Java, showing that the low number of reported cases does not mean South Sumatra is safe from Covid-19. With this modelling we could show that while the government announces the recovery rate to show their supposed successful strategy in mitigating Covid-19, we could show that there are a lot of non-detected cases. We were thus able to counter the government’s narrative that the death rate in South Sumatra is low and that the number of reported cases is small. We show that there would be more reported cases of death related to Covid-19 is testing was higher. We also tried to calm people as the perception was that if they went to the hospital they would die (Figure 5).

Our fourth learning, then, that is useful for policy makers and other stakeholders is that engaging health organisations, and alumni of public health organisations, is a good way to increase health literacy about the danger of Covid-19. We also learned that predictive modelling is important to show more realistically the number of actual cases.

Figure 5: Webinars of “Large-Social Physical Distancing (PSBB) versus New Normal Life”. Tribun Sumsel

Conclusion

From this project, we have learnt a number of things that might be of interest to policy makers and other stakeholders, and things that might be replicable in other Indonesian settings. First, we learnt that with a little support and encouragement, local communities can effectively mitigate Covid-19. As such, those in positions of influence need to listen more closely to community groups. Second, we learnt that Covid-19 information needs to be provided in local languages and presented by trusted members of local communities. These two things – local language and trusted community members – can effectively convey health information. Third, we learnt that university students can be a valuable resource in disseminating information to communities. Fourth, we learnt that engaging health organisations, and alumni of public health organisations, can increase health literacy around Covid-19. We also learnt that predictive modelling is a more realistic way to show the number of actual Covid-19 cases because so few tests are performed. We hope these insights prove useful to others.

References

Adjie, Fiqih Prawira. (2020, May 16). ‘Let’s coexist with Covid-19’: Jokowi calls on residents to adapt to ‘new normal’. Retrieved from https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/05/16/lets-coexist-with-covid-19-jokowi-calls-on-residents-to-adapt-to-new-normal.html

Long, Nick et al (2020). Living in bubbles during the coronavirus pandemic: insights from New Zealand http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/104421/

Worldometers. (October, 7). Coronavirus data worldwide. Retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries

Rosa, Maya Citra. (Agustus, 27). Smart Kampung 13 Ulu, one of the top 21 Innovation in mitigating Covid-19. Retrieved from https://palembang.tribunnews.com/2020/08/27/video-kampung-pandai-13-ulu-masuk-top-21-inovasi-pelayanan-publik-covid-19

Oktavianti, Tri Indah & Kahfi, Kharishar. (2020, July 5). Ministry claims ‘antivirus necklace’ prevents Covid-19, experts beg to differ. Retrieved from https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/07/05/ministry-claims-antivirus-necklace-prevents-covid-19-experts-beg-to-differ.html

Garjito, Dany & Aditya, Rifan (2020 March 4). The ways of communication of MoH-Terawan was criticized, four statements of MoH about Corona become a spotlight. Retrieved from https://www.suara.com/news/2020/03/04/101853/komunikasi-menkes-terawan-dikritik-4-pernyataan-soal-corona-jadi-sorotan

One example of Online opinion by students collaborating with Najmah: Emergency of Hoax during the pandemi by influencers, https://lajusumsel.com/1073-baca-berita-darurat-hoax-di-tengah-pandemi-covid-19-oleh-influencer.html

Moorhead, S. A., Hazlett, D. E., Harrison, L., Carroll, J. K., Irwin, A., & Hoving, C. (2013). A new dimension of health care: Systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. Journal of medical Internet research, 15(4:e85), 1-17. doi:http://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1933.

Yeni, Yeni; Najmah, Najmah; and Davies, Sharyn Graham (2020). Predicitive modeling, empowering women, and COVID-19 in South Sumatra, Indonesia. ASEAN Journal of Community Engagement, 4(1).Available at: https://doi.org/10.7454/ajce.v4i1.1094

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

*This blog is based upon fieldwork conducted by Najmah over the last few months. Returning home after completing her PhD in New Zealand, Najmah was acutely aware of many of the unsafe practices occurring around Covid-19 mitigation. Najmah worked with her supervisor, Sharyn, on writing this blog.