“Speculation is not an activity confined to the world of global finance, real estate, and investors. It extends into conversations and debates about cities, which are increasingly dominated by predictions and prophesies of how cities will fare under conditions of climate change”, writes Dr Emma Colven, Assistant Professor in the Department of International and Area Studies at the University of Oklahoma

_______________________________________________

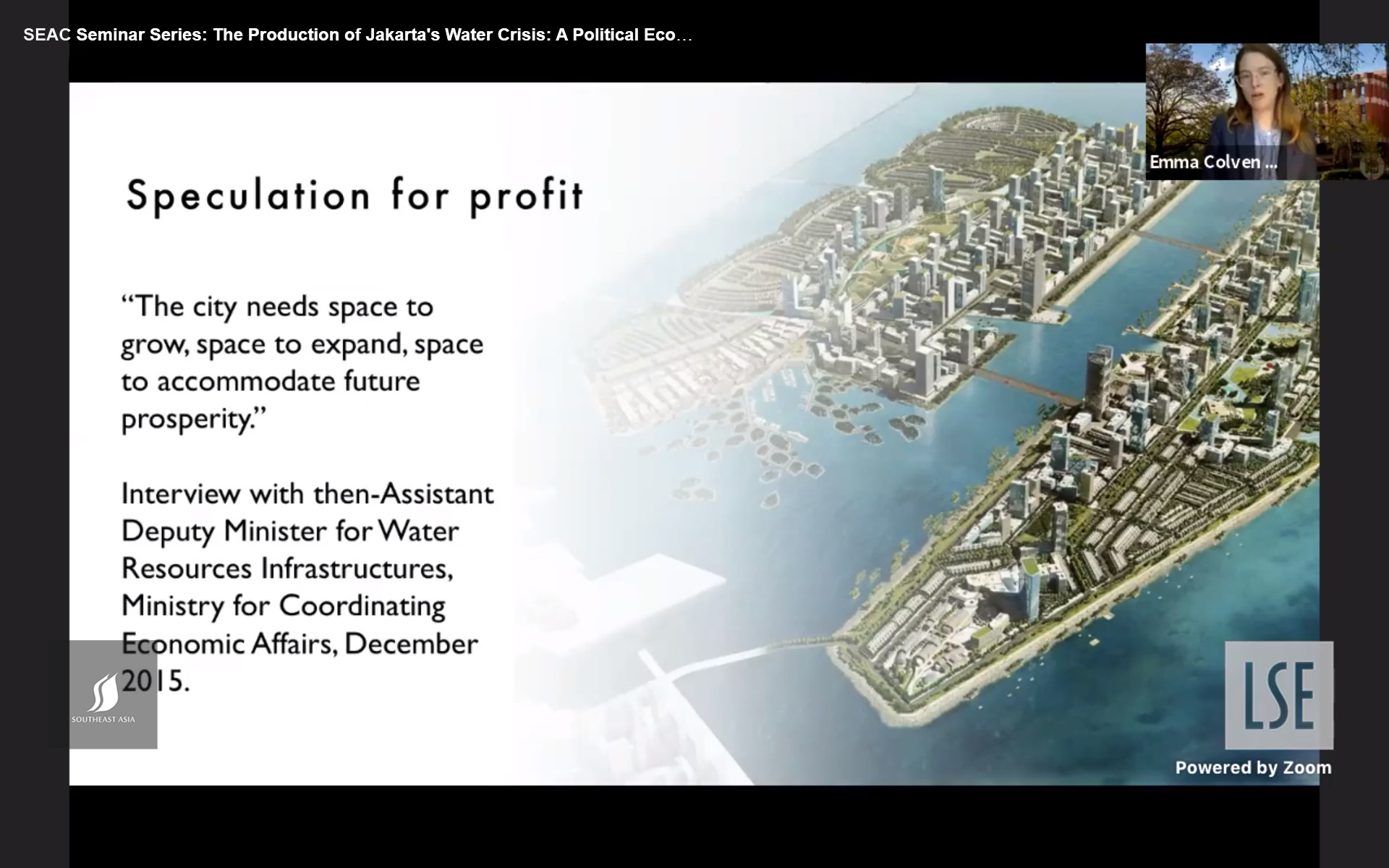

Since economic liberalisation under then-President Suharto in the 1980s, Jakarta’s built, and natural environments have changed dramatically. What was once a relatively small city of kampungs and surrounded by agricultural fields is now a densely populated mega city that, having exhausted space to the mountainous south, is now turning to land reclamation to accommodate its growth. Luxury residential towers, super-block developments, and high-profile infrastructure projects are now commonplace, emblematic of Jakarta’s global city aspirations. Urban development is increasingly made possible by finance capital and speculative investment in land and real estate. In 2014, Frank Knight assessments ranked Jakarta as the world’s hottest luxury project market.

The growing prevalence of finance capital and debt in cities and urban life has prompted researchers to investigate its effects on water resources (Ranganathan 2015; Goldman and Narayan, 2019). Research has also explored the relationship between financial crisis and water crises in cities such as Detroit (Ponder and Omstedt, 2019) and Cape Town (Millington and Sheba, 2020).

My recent talk as part of the LSE SEAC Seminar Series, titled The Production of Jakarta’s Water Crisis: A Political Ecology of Speculative Urbanism, examined how Jakarta’s water crisis has been produced via processes of speculative urbanism. Speculative urbanism, according to Michael Goldman, refers to a particular conjuncture associated with neoliberal economic reform beginning in the late 1980s, that has paved the way for the increased prevalence of finance capital.

Practices of speculative urbanism in Jakarta have not come without social or environmental costs. As finance capital moves in, kampung residents are moved out. New transportation projects, for example, have triggered the state to the forcibly evict people living in informal settlements along soon-to-be railway lines. Rapid urban development has also put enormous pressure on the city’s water resources and infrastructure. Additionally, water catchment areas, green space, and retention lakes have been lost to real estate developments in the pursuit of profit, worsening the extent and duration of flood events. The sustainability of Jakarta’s water supply into the future does not look promising. The city already relies heavily on groundwater resources, which have become overexploited. As a result, Jakarta is subsiding at alarming rates, earning itself the moniker the “sinking city”.

But speculation is not an activity confined to the world of global finance, real estate, and investors. It extends into conversations and debates about cities, which are increasingly dominated by predictions and prophesies of how cities will fare under conditions of climate change. These imaginaries, which can generally reflect either techno-optimism or environmental dystopia, have the power to influence how we plan and envision our cities in the future.

Jakarta’s future is a subject of constant speculation: How long does the city have to act before it is too late? When will it be underwater? The prediction that “North Jakarta will be underwater by 2050” has become a common refrain that is referenced by politicians, the media, and experts alike. These speculations and predictions contribute to producing a dominant imaginary of Jakarta as fated to become a modern-day Atlantis. A poverty of inspiring imaginaries has the potential to limit the kinds of futures that we think are possible. For this reason, it is crucial that seemingly scripted futures be actively unsettled and disrupted.

A number of important points were raised during the discussion regarding, for example, how the trajectories of speculative urbanism might be shaped by the recently passed Omnibus bill and the resulting protests, and how speculative logics intersect with Jakarta’s investments in transportation infrastructure. Having had time to reflect on the discussion, two particular points that were raised strike me as especially productive for thinking about speculative urbanism.

The first point relates to the presence (or absence) of contestation. Several participants in the webinar raised questions relating to activism and grassroots movements: Who is resisting or challenging the practices associated with speculative urbanism? Where is contestation occurring? What opportunities are there to resist practices of speculative urbanism and avoid the seemingly inevitable environmental degradation and social inequalities generated?

A second related point concerned how we define speculation. While I engaged Goldman’s definition of speculative urbanism, scholars such as AbdouMaliq Simone, and Helga Leitner and Eric Sheppard have shown that it is not only property developers and investors who engage in speculation. Residents and communities too engage in everyday acts of speculation both as a means to identify opportunities for profit, and to ensure their own survival.

This is one of the dangers of studying powerful people and processes: we risk overlooking what is happening on the ground, in the everyday lives of residents and how they relate to or contest those processes. The discussion was a useful reminder that scholarship needs to leave space for studying and elucidating counter-imaginaries to the dominant forces that generate environmental degradation and social inequality in our cities. Without doing so, we risk perpetuating the false impression that there are no alternative futures.

* This post is based on Dr Emma Colven’s talk delivered on 14th October 2020 as part of SEAC Seminar Series. You can access a recording of the seminar here.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.