On Wednesday, 14th October 2020, Dr Emma Colven presented a talk entitled “The Production of Jakarta’s Water Crisis: A Political Ecology of Speculative Urbanism” as part of the LSE Southeast Asia Centre’s Seminar Series. Al Lim, a doctoral student at Yale University, reflects on this seminar.

_______________________________________________

Jakarta: a capital sink or sinking capital?

Urban geographer and political ecologist Emma Colven makes the case that it’s both. In this brilliant chiasmus, she refers to how the city has a dual role—a financial hotbed for potential investors as a capital sink and the sinking capital of Indonesia (up to 20cm in some parts of the city). Here, the capital logics that drive financial investment are juxtaposed with the violence of environmental degradation and its impacts on urban residents.

Colven’s talk brings the audience through two imaginaries of Jakarta, explored its political economy and political ecology, and spoke to the speculative urbanism geared towards profit and survival. The calculus of risk and finance intersects in fascinating ways with the materially produced and socio-ecological flows of urban water. Thus, her investigation demonstrated how the ‘water crisis’ as a key lens to understand the socio-spatial unevenness of speculative urbanism and the city’s transformation.

Jakarta, a capital sink: the city has been trying to attract global investment and capital by portraying itself as a world-class centre for economic growth, emerging as the world’s hottest luxury real estate market in 2014. The sheen of steel-and-glass of the city’s projected identity builds on notions of financialization and speculation—a future-oriented, risk-taking endeavour as a mode of urban governance through neoliberal economic reforms. Through the value capture of transnational capital, this investment strategy commodifies and radically transforms the urban landscape.

Jakarta, a sinking capital: the attraction of capital is contrasted with a more dystopic picture of the city steeped in developmentalism and predicted to be underwater within the next few decades. The threat of flood and insufficient water has long been a problem for Jakarta’s urban development. The over-extraction of water from its aquifers has compounded the problem of land subsidence. And the city continues to sink, significantly increasing flood vulnerability for many of its marginalized populations.

By pointing out the connection between these two dynamics, capital sink/sinking capital, Colven directs our attention to the extractive processes of financialization directly worsening the city’s environment. This is evidenced in two case studies through the valences of speculation as profit and speculation as survival.

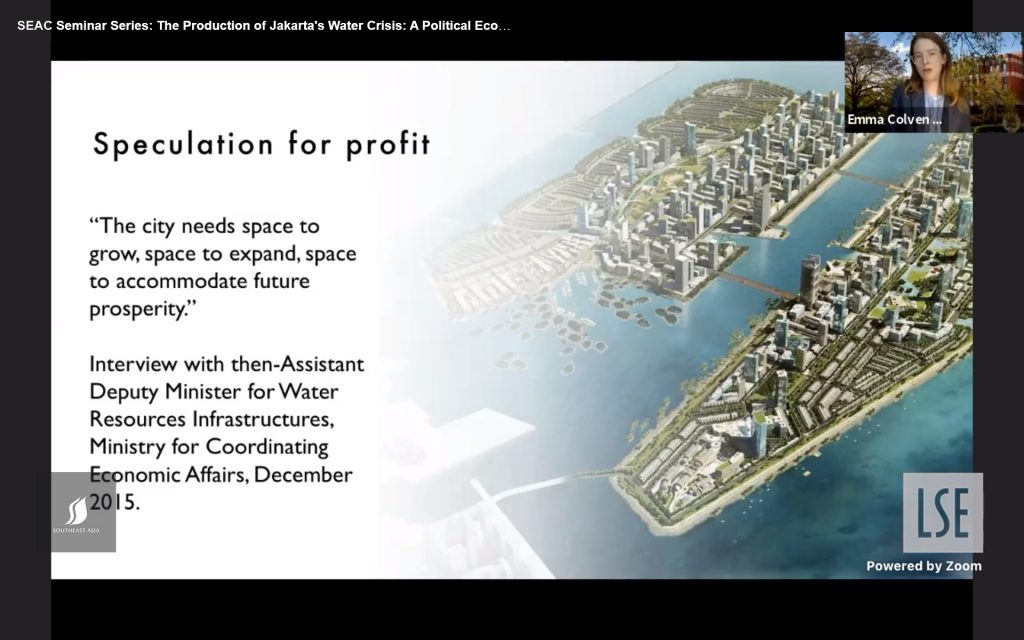

Colven portrays the process of speculation through water infrastructure through the 17-islands project and the National Capital Integrated Coastal Development (NCICD) Masterplan. The 17-islands project is a land reclamation development, attempting to grow and extend Jakarta’s urban boundaries over the sea with artificial islands. However, these will definitively produce negative impacts on the environment and natural drainage systems. It has faced immense resistance from fishing communities and environmental activists, whose concerns seem to vastly differ from those investing in the project. The investors’ interest in capital over the place itself was captured in Colven’s interview with a financial consultant who mentioned that “they are not interested beyond five years. They [investors] sell and are long gone.”

Environmental degradation is not only exacerbated by such developments, but they have also become the locus of new investments like the NCICD’s sea wall. In other words, capitalist activities disguise themselves as environmental to instrumentalise the landscapes for profit generation. In this manner, the real estate development masquerades as a coastal defence.

Yet the future remains open. Will the city be abandoned and allowed to flood in an apocalyptic scenario? Or will there be adequate state intervention to protect Jakarta from worsening environmental degradation? With Indonesia’s capital projected to move to East Kalimantan, the ongoing climate crisis, and the current pandemic, the implications of financialization and water management become ever-more prescient.

A compelling and evocative presentation, Colven’s research brings up the questions of temporalities and comparative urbanism. The disconnected understandings of time in Jakarta between investors’ short-time profit strategies and long-term environmental sustainability are in clear tension here, especially with Indonesia’s moving capital. Moreover, the intersection of the slow environmental violence (Nixon, 2011), the fast developmentalism characteristic of many Asian cities (Shin et al., 2020), and the possibilities of ‘slow’ and ‘moderated’ time (Shaban and Datta, 2019) raise important questions about the politics and unevenness of temporality in the city’s developments.

The story of capital’s role in urban dynamics of dispossession is not limited to Jakarta either, in part due to the global character of capital and the investor. The mystical qualities of global financial circuits have manifested in material dispossession, as evidenced in the ‘legal fictions’ of Cambodia (Nam, 2020), and the luxury and rubble of Ho Chi Minh City (Harms, 2016) to name two examples among numerous cities caught in this trap. Colven’s presentation is thus generative of questions of comparative or conjunctural urbanism to engage the multi-scalar connections/disconnections in these processes (Robinson, 2016; Sayın et al., 2020). Further, the spectre of the ‘investor’ haunts financial circuits as an invisible yet important agent in these transactions. Is the future to be determined by these investors’ accumulation logic, or what alternatives might there be?

References

Harms, E. (2016) Luxury and Rubble: Civility and Dispossession in the New Saigon. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Nam, S. (2020) ‘Fiction, fraud, and formality: the legal infrastructure of property speculation in Cambodia’, Critical Asian Studies, 52(3), pp. 364–377. doi: 10.1080/14672715.2020.1798260.

Nixon, R. (2011) ‘Slow Violence, Gender, and the Environmentalism of the Poor’, in Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 128–149.

Robinson, J. (2016) ‘Comparative Urbanism: New Geographies and Cultures of Theorizing the Urban’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(1), pp. 187–199. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12273.

Sayın, Ö., Hoyler, M. and Harrison, J. (2020) ‘Doing comparative urbanism differently: Conjunctural cities and the stress-testing of urban theory’, Urban Studies, p. 0042098020957499. doi: 10.1177/0042098020957499.

Shaban, A. (2019) ‘Towards “Slow” and “Moderated” Urbanism’, Economic and Political Weekly.

Shin, H. B., Zhao, Y. and Koh, S. Y. (2020) ‘Whither progressive urban futures? Critical reflections on the politics of temporality in Asia’, City, 24(1–2), pp. 244–254. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2020.1739925.

* This post is based on Dr Emma Colven’s talk delivered on 14th October 2020 as part of SEAC Seminar Series. You can access a recording of the seminar here.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.