Around 123,000 immigrants acquired British citizenship in 2017, putting the UK in second place among European countries for number of naturalisations granted. This figure is expected to grow as more Europeans are applying for citizenship, following Britain’s decision to leave the EU. Policy makers test the loyalty and adequacy of applicants through the “Life in the UK” test and a challenging application process. Their concern is that immigrants and their children cannot be loyal towards more than one nation and that this threatens the social cohesion of the country. The “Life in the UK” test is especially designed to measure immigrants against an unrealistic ideal British standard. In my research I question the need for such tests as I find that the immigrants who naturalise identify as British and are as politically disengaged as the native British population.

We know that people acquire citizenship for the security it grants and because it improves peoples’ life chances, but is this the whole story? Is citizenship simply a means to an end? I argue that, similarly to the native population, citizenship for immigrants is not only a legal status that grants rights and benefits, but it is also a marker of national identity.

Using representative data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study data, I analyse a sample of 997 immigrants, 407 of whom acquired citizenship between 2009 and 2016 and 590 who did not. I investigate differences between the two groups in the strength of their British identity and in their degree of political engagement before and after citizenship acquisition.

Immigrant citizens feel British

I find that, net of other factors, the immigrants who identify as British are much more likely to naturalise at a later point. In addition, the importance they give to their British identity grows after naturalisation. Consistently with theories of social identity, these findings suggest that immigrants seek the official legitimisation of their national identity when they already identify as British. The official recognition sanctioned by the passport then completes their sense of national identity, which therefore intensifies. Succeeding in naturalising after the challenging and costly application process may also boost the importance given to a British identity by fostering a stronger claim to it.

Immigrant citizens are disengaged with politics

In contrast and surprisingly, I also find that the immigrants who are the least interested in politics are the ones to be most likely to later naturalise and that their interest in politics continues to decline thereafter. These findings are puzzling because we would expect the most politically engaged to be more motivated to acquire citizenship since it grants the right to vote. However, the relationship between political engagement and naturalisation may not be clear-cut. We know that the British majority population is highly disengaged with politics. Only two thirds of British citizens voted in the last few general elections and even fewer vote in local and European elections. It follows that if the acquisition of citizenship signals integration with the majority population, immigrants’ level of political engagement should be as low as that of the native population. In support of this argument I find that non-citizen immigrants are more interested in politics not only compared to citizen immigrants, but also compared to natives. The fact that interest in politics continues to decrease after naturalisation may also indicate that the immigrants who identify as British and have been granted British citizenship may feel disillusioned and disappointed by a political discourse that excludes them. The dissonance between subjective perception of belonging and the political narratives and empirical realities of exclusion might push people to further disengage especially after the acquisition of citizenship.

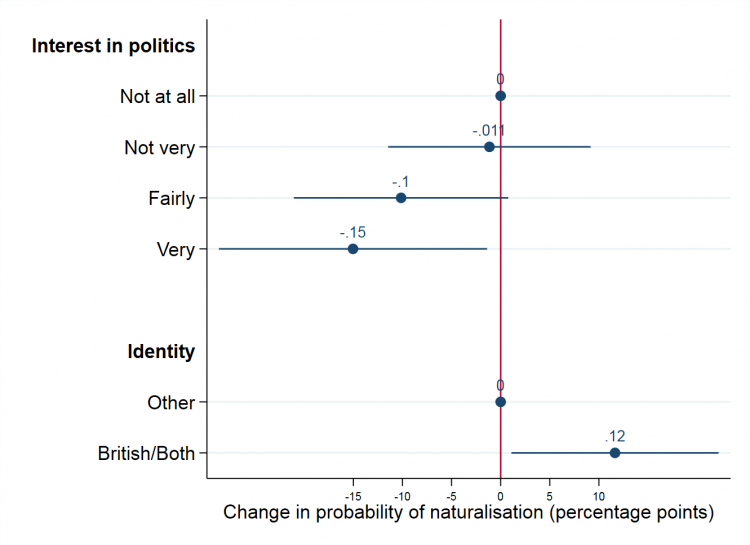

Figure 1: Before citizenship acquisition the likelihood of acquiring citizenship deceases by up to 15 percentage points for the very interested in politics and increases by 12 percentage points for those who identify as British.

Note: Average marginal effects computed after the probit model of the probability of acquiring British citizenship with clustered standard errors and weights. Circles show point estimates and the horizontal lines delineate 95% confidence intervals. Circles without horizontal lines show reference categories. Estimates control for sex, age, age squared, years of residence, HDI of country of origin, Europe indicator, Commonwealth indicator, gross household income, home ownership, age left education, whether any education in the UK, presence of children, whether any children born in the UK, partnership status, employment status, language proficiency, familiarity with the political system.

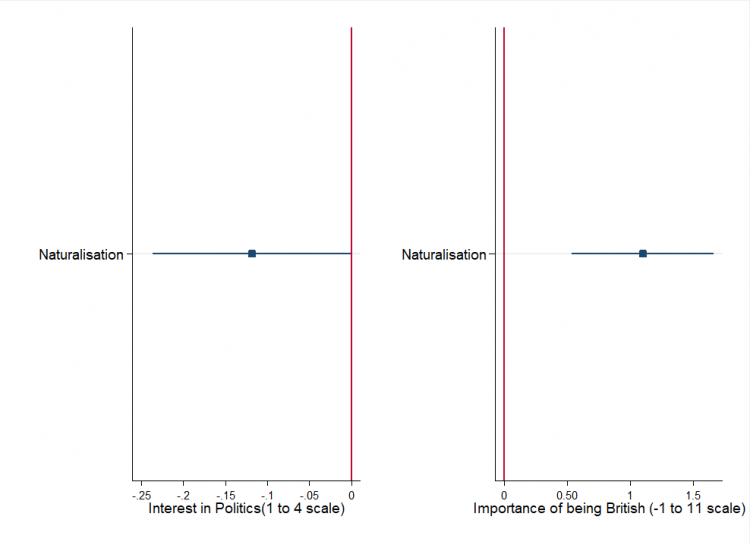

Figure 2: After citizenship acquisition interest in politics drops by 2.75%, i.e. by 0.11 on a scale of 1 to 4

After citizenship acquisition the importance of being British increases by 9.2%, i.e. by 1.1 points on a scale from -1 (do not consider themselves British) to 11 (they give very high importance to being British)

Note: Average treatment effects (ATE) estimated through inverse-probability weighted regression-adjustment (IPWRA) on the level of interest in politics and on the degree of importance given to a British identity. Circles/diamonds show point estimates and the horizontal lines delineate 95% confidence intervals.

Does integration mean identifying as British and being uninterested in politics?

In sum, immigrants naturalise once they already feel and act as citizens, i.e. they identify as British and show low political engagement. After citizenship acquisition, the importance they give to their British national identity grows stronger and their political engagement weaker. These findings raise questions, both for researchers and for policy makers. Since immigrant citizens, who can vote and are permanent members of the UK, feel and care about their British identity, do we need to worry about them failing to embrace a British national identity? Do we need to test their loyalty through citizenship tests?

In contrast, as political disaffection is high in most Western countries, how far does it make sense to regard political engagement as a defining feature of citizenship? Is it fair to expect immigrants to pass a citizenship test that asks them questions that most native British people are unlikely to know the answer to, including about 278 historical dates and the number of elected representatives in each regional assembly, for example? In our ideas and policies for successful integration we should be mindful of the native population against which we are comparing immigrants.

The related article can be found here.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Love your thoughts in this article! It’s a thoughtful consideration of a super important topic. The relation between the probability of naturalising and interest in politics is one I would imagine many people haven’t considered before either!

If you could provide more light on two areas I believe this might be helpful to the reader (although more complex so I can appreciate why you would leave them out here 🙂 ).

First, could you provide context to the claim “We know that the British majority population is highly disengaged with politics”?

Second, how do you define “interest in politics”?

I would suggest that post-referendum Britain is simultaneously frustrated with its political system (ie, disengaged), but also highly polarised in opinion (ie, engaged). Therefore, the claim that ‘the British population is disengaged with politics’ seems a strong assumption. If you nuance this claim using a wider variety of different definitions for “interest in politics”, it would be fasinating to see how such insights might impact your conclusions on naturalisation and citizenship. It might also make your conclusions less reliant on an assumption which could be perceived as subjective.

All the best 🙂

Thanks for your comment!

In response to your questions: interest in politics is measured as a direct question “How interested are you in politics?”, the possible answers going from “not very” to “very”. As for the grounds on which I claim that the native population shows low political engagement, I looked at the level of interest in politics for natives in the same survey. I compared non-citizen immigrants, citizen-immigrants and natives. Non-citizen immigrants showed the higher level of interest.

This said, this is one of the possible explanations I offer to make sense of the negative relationship between interest in politics and naturalisation. In the paper I discuss and look into (when possible) other possibilities. I also use another measure of political engagement, familiarity with the political system. I think more research is definitely needed to better understand this relationship, especially with other measures of political engagement.