The key conclusion of the game theory of economics is that collaboration is an optimal way to pursue solutions for society at large. On the qualitative side, a recent study on 10 locally-led projects from across the UK finds that collaboration between communities and local governments has broad appeal as a solution to intractable social problems that we struggle to address as a society. The allure of collaboration is considered self-evident: by leveraging the synergies formed by working together, innovation is possible, new knowledge is built, and complex, intractable social and economic problems can be resolved collectively.

Still, leaders across sectors struggle to embed collaborative working into and across their organisations meaningfully. In this blog, we articulate the nature of these barriers and suggest routes for overcoming them in the public service sector.

I. What are the barriers to collaboration?

Barriers to collaboration are thought to stem from two economic assumptions. First, maximisation, that every economic agent is a rational decision-maker with a clear understanding of the world. Second, consistency, that the agent’s understanding and expectations of other agents’ behaviour is correct. In practice, however, we know that these assumptions regularly fail. Humans are often not rational actors, and our understanding of others’ behaviour is mutable at best. Truthfully, there are myriad variables at play, the assumptions above as well as context-specific ones, including the human element of mutual trust. These variables are a product of a dynamic process in which individuals and organizations choose to work together – or not.

II. How might we overcome the barriers to collaboration?

Based on these economic assumptions, efforts to overcome collaborative barriers have focused mainly on the interplay of incentives and motivations to pursue them. This approach has led to dedicated research streams on tweaking incentive structures and methods to formalize relationships through contracts.

A growing body of work, however, focuses on the relational and human elements of working together. Real-life collaborations are not so easily distilled into a single stark choice lacking prior information. Collaboration, in its true sense, is perhaps better understood as an ongoing series of choices supported by an agreed way of working. Our experience and our expectation of future interactions inform the choices we make. For example, you are less likely to cooperate with someone who has betrayed you in the past, and you are less likely to betray someone who might have the opportunity to return a future favour.

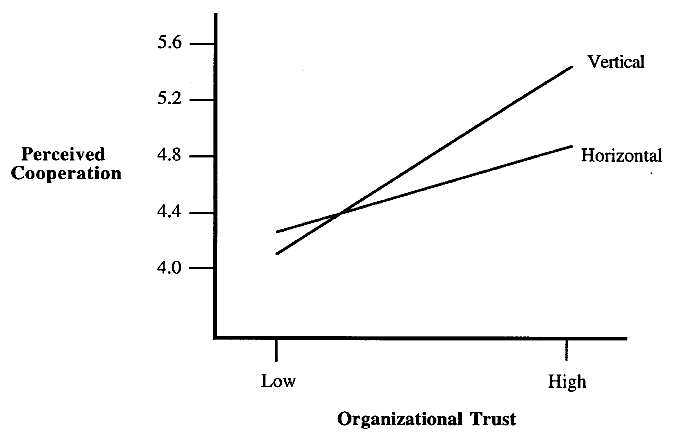

This topic is discussed amongst scholars advocating in favour of trusted relationships as a tool to improve productivity. For instance, Collier (2019) believes a remedy for many current crises in highly developed countries is to re-establish core beliefs in mutual obligation at all levels: global, national, corporate, and familial. However, there is evidence that trust is less effective in enhancing horizontal alliances between similar organisations, compared to vertical ones between organisations and their upstream or downstream partners (Rindfleisch, 2010).

Figure 1. Effect on perceived trust

In the world of public services, there is some consensus that government-backed regulation and process constrain substantive collaboration amongst providers and across sectors and that there is a need to reevaluate the environment for service procurement and delivery. These challenges may require signalling that the market will collectively transition from a zero-sum game to a positive-sum game. Indeed, contemporary collaborative reform tools – systems thinking, collective impact initiatives, and purpose-oriented networks – identify a distinct need for a shared vision and common goals for collaborations to prosper. This common goal can harmonise incentives of the players and lower the potential for costly trade-offs usually taken to secure partnerships (e.g. forgoing specificity).

III. Is collaboration economically justified for public service provision?

Importantly, collaboration is not necessarily the cheapest option. In the UK, where austerity has bitten for over a decade, collaborative approaches cannot be justified on a cost-saving basis. However, they could potentially deliver better value for money when examined through the cost-effectiveness approach. In other words, pooling resources from multiple players could potentially improve effectiveness (numerator) and offset the higher transaction costs of developing such a partnership (denominator). Also, smaller entities might benefit from collaboration by capturing scale economies unavailable to them individually, since organisation size is a constraining factor in public service efficiency (Elston et al., 2018). However, this bond could equally fail if not established properly, leading taxpayers to bear the additional, and often underestimated, costs of these interactions. Overall, where social problems are unclear and solutions unknown, collaboration is the mechanism through which disparate organisations can come together to deliver multi-actor solutions.

Policy tools that address some of these fiscal concerns are proliferating; for example, outcomes-based commissioning attempts to join actors by specifying and incentivising outcomes that can be jointly delivered. Likewise, there has been a growth of collaboration in UK local governments, many of which seek to mobilise community assets by creating a shared vision of what a prosperous community looks like (e.g. The Oldham Plan, The Wigan Deal). However, it is unclear yet whether they will promote effective collaboration.

References:

Collier, P. (2018). The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New Anxieties. London: Penguin UK.

Elston, T., MacCarthaigh, M., & Verhoest, K. (2018). Collaborative cost-cutting: productive efficiency as an interdependency between public organizations. Public Management Review, 20(12), 1815-1835.

Rindfleisch, A. (2000). Organizational trust and interfirm cooperation: an examination of horizontal versus vertical alliances. Marketing Letters, 11(1), 81-95.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.