Milan Vaishnav questions whether regional political actors threaten the status of India’s national political parties. This post is an excerpt of an article first published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The “rise” of regional political parties seems to be an eternal theme on the Indian political scene. Indeed, it has become a standard trope of Indian political analysis to deluge readers with excited descriptions of India’s fragmented party system and the multiplicity of local parties that appear to crop up like weeds after a monsoon rain. Observers also like to note the continued decline of India’s two genuinely national parties, the Indian National Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

There is, of course, a kernel of truth to these claims. Many of the leading power brokers in contemporary Indian politics hail from regional parties—such as former chief ministers of Uttar Pradesh Mulayam Singh Yadav and Mayawati as well as Chief Minister of West Bengal Mamata Banerjee. Looking at them, it is not hard to believe that times have changed.

There is plenty of hard data to back up this sentiment. The exponential increase in the number of parties contesting elections, particularly over the past two decades, and the shrinking margins of victory in parliamentary elections are direct results of the emergence of new regional power centres. At last count, the fifteenth Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament, boasted 38 parties, all but two of which are largely ethnic, regional, or subregional enterprises.

The rise of regional parties has indisputably transformed the very nature of electoral politics in India. For the foreseeable future, it is unimaginable that a single party could form the government in New Delhi—a testament enough to this tectonic shift.

But whether regional parties will be able to wrest greater control over the shape of governance in the capital and in India’s states remains an open question. There is an unfortunate, unswerving progression to the conventional narrative, which treats regional parties as constantly on the rise, acquiring greater political space. In fact, there are a number of trends that indicate regional parties may not be the juggernauts many observers make them out to be.

A common myth about regional parties is that their rise, by definition, has eroded—and continues to erode—the stature of national parties. But in reality, after a period of unprecedented growth in the standing of regional parties during the late 1980s and early 1990s, the pattern of electoral competition at the national level has achieved a surprisingly stable balance of power.

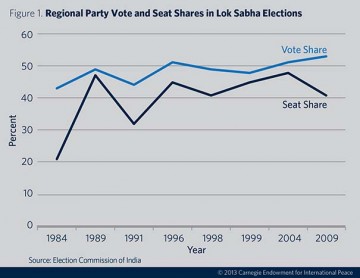

The aggregate vote shares won by the two truly national parties and “the rest,” meaning primarily regional parties, in the past five elections illustrate strikingly that the respective popularity of these two groups is in a rather steady holding pattern. The share of votes won by regional parties cracked the 50 per cent mark for the first time in 1996. Then the engine sputtered somewhat. By 1999, vote share of regional parties had dipped to 48 per cent. By 2004, their vote share crept back up to 51 per cent, the same level it had been eight years earlier, before modestly rising again in the 2009 elections.

What’s more, the doomsday scenario in which the rise of regional players directly threatens the status of national players overlooks the possibility that regional parties can also hurt one another. In India’s winner-take-all electoral system, where victories are possible with a small minority of votes in any given constituency, increasing levels of political competition have led to a greater fragmentation of the vote. In 2009, for instance, less than a quarter of electoral districts were won with a majority of votes. The net result has often been regional parties crowding out other rival regional parties. See, for example, the electoral impact of the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena party, which took votes away from its key regional rival, the Shiv Sena, in the state of Maharashtra. And competition between upstart and established Telugu regional parties in Andhra Pradesh redounded to the benefit of the Congress Party.

The increasingly fragmented vote has affected the share of seats won by regional parties in Lok Sabha elections. At present, regional parties occupy 41 per cent of the seats—the same share they held in 1998. This is actually a decline from the two previous election cycles. Regional parties’ vote share reached its highest level in 2009 (53 per cent), but the share of seats allocated to regional parties declined because of fragmentation (see Figure 1), suggesting that the proliferation of regional parties risks cannibalising the “non-national party” vote share.

One way in which regional parties were believed to threaten national parties was by developing into national players in their own right. However, this fear has not come to pass, as even the most prominent regional parties have had difficulty parlaying their regional standings into national success. For instance, in the 2009 general election, Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party fielded candidates in 500 of 543 constituencies across India (incidentally, that is more than any other party). Yet, the party took home only 21 seats—all in its bastion of Uttar Pradesh. In fact, the Bahujan Samaj Party was not even a contender in the vast majority of constituencies in which it entered the fray; its candidates finished among the top two in 72 constituencies in all. Contrast this with the Congress, which contested 440 seats, won 206, and was a top-two finisher in 350 seats around the country. The BJP bagged 116 seats and finished second in another 110 constituencies.

The emergence of regional parties as major centres of power in India’s politics, economics, and society is one of the most important developments in the country’s post-independence history. And come the general election in 2014, regional parties will play a pivotal role in helping to influence the formation of the next union government. It is even possible that India’s next general elections will produce a “third front” government headed by the leader of a regional party.

Yet, the regional revolution in contemporary Indian politics should not be overstated. India’s regional parties have indeed already risen; whether they can rise further is unclear.

Milan Vaishnav is an Associate of the South Asia Programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Click here to read more of his analysis of India’s regional parties.