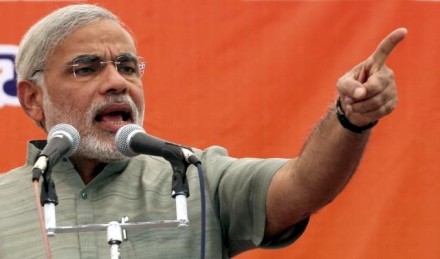

Siddharth Bannerjee deconstructs frontrunner Narendra Modi and appraises the electoral prospects of the Bharatiya Janata Party in the upcoming Indian elections.

India today stands at a civilisational crossroads. Despite the latest indications that the recent slowdown in its overall economic output is edging back upwards and that skyrocketing domestic inflation is cooling down, worries about the levels of large-scale corporate and public-sector collusion and corruption, alarming rates of gender-based discrimination, disturbing instances of racial intolerance, and a creeping sense of censorship in the public sphere coupled with the suppression of healthy debate remain outstanding issues in the national psyche. Consequently, the decision its citizens make in the upcoming 2014 parliamentary elections will determine what cultural, economic and political course this tremendously diverse country takes in the next decade and beyond.

Taking into account the sheer size and scope of humanity involved, ‘the world’s largest exercise in democracy’ is interesting as a societal spectacle: nearly 815 million eligible voters (100 million of whom are newly enfranchised) will participate in a nine-phase polling plan spread over 35 days from 7 April to 12 May (with counting of ballots and results being declared on 16 May). But equally, the divisive and challenging nature of issues up for consideration in the present political landscape marks this electoral iteration as a critical juncture in Indian history.

As it stands, India has three paths ahead of it. If it were to continue on the same course as before, it will be supporting the social-democratic and gradually neo-liberal path championed by the Congress Party and its allies. This seems unlikely given the pervasive anti-incumbency sentiment across the country that blames the Congress for ineffectual and corrupt governance. The second option for Indians is to turn sharply leftward and throw their support behind an assorted mix of regionally strong and populist parties. This ‘Third Front’ got some traction in the lead up to elections, but with no party looking to gain a majority of the 272 seats needed, the parties in this grouping are waiting to see how the balance of power plays out on 16 May. But if it were to veer rightwards, India will choose to go down the Hindu nationalist path promoted by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its recently ascendant leader, Narendra Modi. This seems the most likely outcome of the upcoming elections, with the BJP slated to win between 35 and 40 per cent of the seats in parliament and Modi topping opinion polls as clear frontrunner for the prime minister’s post.

The Contender

Whenever discussions of Modi as prime minister surface, questions about his level of complicity in the 2002 Gujarat communal riots arise. Notwithstanding his clearance by the Special Investigation Team for lack of evidence, it will always remain a stain on the reputation of India as a liberal democracy that a state permitted such an event to occur and that the majority of the perpetrators remain scot-free due to the laxity of public officials. Perversely, Modi’s handling of the Gujarat riots, along with the manner in which he trumped internal party leadership candidates and his moves to centralise power have served to enhance Modi’s reputation as a strong-man Hindu leader and galvanise support among certain fringe elements in the Sangh Parivar. This resurgence of the Hindu right is causing palpable unease amongst a number of constituencies including sexual and religious minorities, gender rights groups, and other civil society campaigners.

On social policy matters, Modi is a conservative in every sense of the word—not surprising given that his cultural moorings are tied to those of the largely upper-caste Hindutva ideology of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). For example, based on his own success story of overcoming the odds as a tea stall owner, he has always been against the implementation of reservation quotas for ‘other backward classes’ in the public sphere—the leitmotif of left-leaning and populist parties in India. Over and above his personal philosophies and religious convictions, Modi is also known for being a charismatic but authoritarian leader who is obsessed with controlling his messaging and portrayal in the media. In this last instance, Modi personally, along with the BJP’s well-funded public relations apparatus, have the capacity to saturate the public sphere with a sort of hyperactive social, electronic and print media coverage reminiscent of US presidential-style elections. Taken together, Modi is able to project an image of an energetic and capable administrator who can cater to the burgeoning Indian middle-class desire for global goods and world-class services. The carefully curated persona of a super-CEO fits in well with this rapidly crystallising cohort which is reliant on the private sector for quotidian concerns from its children’s education to healthcare and personal security.

But Modi’s trump card is his deft handling of Gujarat’s economy. Citing his ‘vibrant Gujarat’ model of success based on his decisive administrative style, public sector reforms and accompanying build-up of infrastructure projects, Modi claims he has attracted scores of investors and promoted a business-friendly climate in his home state. This is partially true in the sense that Gujarat is certainly business friendly, but not necessarily market friendly. Most of the investment is domestic in origin and was facilitated by the fact that Modi has a personal rapport with major Indian industrialists. A good example of this is the Tata Nano episode when Modi welcomed the setting up of a car manufacturing plant in Gujarat after it was facing operational hiccups in West Bengal. These deals, while expedient, have raised concerns regarding delaying tactics in conducting environmental impact scans and financial irregularities in the sale of land, and the procurement of highly favourable loan interest rates and tax breaks as outlined by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (and cottoned on to by opposition parties such as the Aam Aadmi Party).

Internationally, various governments, including the United Kingdom and United States, which had imposed a travel ban on Modi for his alleged complicity in the Gujarat riots, are now showing rapprochement as they realise that he could be the next democratically elected prime minster of a major economic power. Regionally, Modi has adopted a tough stance against the ‘expansionist’ ambitions of China vis-à-vis the border states of Arunachal Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir, calling instead for robust trade ties between the two neighbours.

That said, Modi’s biggest foreign policy challenge, were he to lead India, would be how to deal with the situation in Afghanistan (and by extension, Pakistan) when NATO troops are withdrawn by the end of 2014. Given the likelihood for uncertainty in the region after the pull-out, there is growing concern that Islamic terrorist outfits affiliated with the Taliban and al-Qaeda may target India in the guise of attacking the Hindu nationalist ideology of his BJP. Exacerbating the situation is the fact that the Indian army has been in dire straits, with top posts left unfilled, a woeful personnel retention record of senior army corps and the vanishing of minorities (now less than one per cent, discounting Sikhs) from all levels of the military. The recent move by General V. K. Singh to join the BJP is perturbing in this regard because the Indian armed forces have normally stayed out of politics and in fact have always taken their orders from the civilian command.

Getting down to brass tacks, we see that the ‘Modi wave’ has translated into tangible gains in voter support in the electorally vital states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar (which together account for roughly 25 per cent of seats in Parliament). This is why Modi’s contesting a seat from Varanasi (one of Hinduism’s holiest cities) comes off as both a symbolic and pragmatic manoeuvre. At present, BJP’s projected national total falls in the range of 170-220 Lok Sabah seats, with or without its National Democratic Alliance (NDA) allies.

Meanwhile, the Congress is predicted to have its worst-ever showing, and is not expected to win more than a hundred seats, effectively ruling them out of any governing calculus. Regional parties, which are powerful in the south and east of India, are better at getting a higher proportion of the vote share, but are handicapped by the first past the post (FPTP) system and thus face difficulty converting their votes into parliamentary seats. Moreover, there are numerous regional parties, and most are left battling amongst themselves in a multi-cornered fight. Consequently, if the BJP wins around 170 seats, they might have to give ground to regional parties whose leaders are certain to challenge Modi’s mandate to be the prime minister, and make installing one of their own candidates as PM a prerequisite for coalition formation. In this scenario, these regional parties, in concert with populist national parties like the AAP and a few independently elected MPs, could form a non-contentious axis for a third front alliance or could coalesce around a secular, anti-Modi platform.

Looking ahead

Civil liberty defenders in India are growing concerned that the ascent of the Hindu right epitomised by Modi’s rise will shrink the already confined and heavily patrolled space for public deliberation and in the arena of personal privacy. They worry that freedom of expression might be adversely affected in the name of safeguarding majoritarian public sentiment as the pulping by Penguin Publishing of Wendy Doniger’s book and the cancelling of an ‘anti-national’ play illustrate. Modi and the BJP are trying to get away from being characterised in this mould, but are hampered by their long-standing ties to (mostly) men who have extremely uncivil aspirations. At the personal level, Modi’s penchant to centralise power and control nearly every aspect of administration has raised the hackles of even his own party’s leaders.

But what Modi and the BJP lack in nuance is made up in sophistication, with slick electronic media and mobile marketing campaigns that are well versed in tactics such as micro-targeting and an inundation of social networking platforms. The dominant message is to keep broadcasting their economic credentials, but Modi should be cautious of the past failures of the ‘India shining’ strategy that cost the BJP the 2004 election. If elected, Modi is likely to rule in the pro-corporatist style of Abe of Japan, Erdogan of Turkey or Rajapaksha of neighbouring Sri Lanka.

Of course, predicting elections in India is a notoriously fraught business (not helped by polling companies willing to skew results in favour of the party that pays them), but the demographic breakdown has always meant that elections are decided in the numerous farming villages and small towns that make up the Indian country side.

Thus far no viable alternative candidate of any stature has emerged on the national stage, and so this is indeed a golden opportunity for the BJP to win this bout. If Modi and the BJP are somehow able to connect with the underserved rural and peri-urban constituency, they might approach an outright majority. But given his polarising presence, the challenge for Modi will be to overcome the thriving cult of divisiveness surrounding his persona and unite his disparate compatriots at this pivotal moment in their history.

Siddharth Bannerjee is a graduate of LSE’s MSc in Social Policy and Development and works on governance reform initiatives, especially ones involving the use of innovative technology and open source data.