LSE’s Gautam Appa explains why claims that Narendra Modi has received three ‘clean chits’ for his alleged role in communal riots in Gujarat in 2002 are distorted.

On three occasions – one each in 2011, 2012 and 2013 – the Supreme Court of India has supposedly absolved Narendra Modi, the Chief Minister of Gujarat and the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate in the upcoming elections, of culpability in Gujarat’s communal riots of 2002. But a case against Modi has never been registered in the Supreme Court. So how has the court given him a ‘clean chit’ without being asked to adjudicate the matter? And on what basis does Modi claim a clear conscience with regard to the 2002 violence in Gujarat?

A clean chit for what?

The question the Indian courts are considering is whether there is prosecutable evidence against Modi to establish criminal liability for his role in the 2002 riots in Gujarat, which claimed the lives of more than 2,000 people and made 200,000 people, mainly Muslims, homeless. There are allegations that Modi masterminded the riots; more specifically, he is accused of the following:

- allowing the charred bodies of 54 Hindu victims of the Godhra train fire to be paraded in the streets of Ahmedabad

- supporting a Gujarat bandh (closure) announced by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), a Hindu fundamentalist organisation, thereby facilitating riots

- directing senior police officers not to interfere if Hindus sought revenge

- placing two cabinet colleagues in the police control rooms to ensure compliance with his directives

- penalising upright police officers and rewarding compliant ones

- appointing partisan public prosecutors berated by the Supreme Court for “acting like defence counsel”

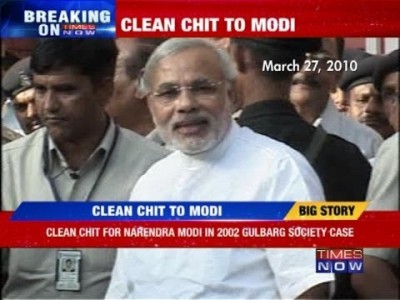

The Supreme Court in 2008 appointed a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to look into nine riot cases, removing them from courts in Gujarat. A year later, the Supreme Court asked the SIT to investigate a criminal complaint against Modi, filed by Zakia Jafri in 2006. The Gujarat police had done nothing about the complaint, so Zakia had filed a case in the Gujarat High Court to get the police to act on the complaint. When the High Court rejected this, Zakia referred the matter on to the Supreme Court. Modi’s three so-called ‘clean chits’ from the Supreme Court relate to this case.

Zakia is the widow of Ehsan Jafri, a former MP and state Congress Party member, living in Gulberg Housing Society in Ahmedabad. When news of the slaughter of Muslims following the Godhra train fire in 2002 started trickling through, scores of frightened Muslim neighbours gathered in the Jafris’ home believing that Ehsan’s connections would help ensure their safety. As a violent mob advanced on Gulberg, Ehsan made repeated phone calls to the police and political authorities – in Ahmedabad, Delhi, and even to Modi himself – pleading for help. But none came, even though police were present in the area. Eventually Ehsan and 68 others were massacred, many of them burnt alive. According to eye witnesses, Ehsan’s severed head was hoisted on a trident.

The SIT investigating Zakia’s complaint ran into difficulties. First, the Supreme Court had to drop two of its officers as they were found to be untrustworthy. Then, in 2010, the special public prosecutor working with the SIT resigned, saying by way of explanation that “I am collecting witnesses who know something about a gruesome case in which so many people, mostly women and children huddled in Jafri’s house, were killed and I get no cooperation. The SIT officers are unsympathetic towards witnesses, they try to browbeat them and don’t share evidence with the prosecution as they are supposed to do.”

After all this, when the SIT filed its interim report, the Supreme Court took the unusual step of asking an eminent advocate, Raju Ramchandran, who was already appointed as an Amicus Curiae (friend of the court), to assist in this critical case and visit Gujarat, independently assess the evidence generated and meet with witnesses directly.

According to the law, once the investigation is over, the Supreme Court stops monitoring and asks the Investigating Agency to file a report before a Magistrate who decides whether there is a case for prosecuting any of the accused. On 12 September 2011, after reviewing Ramchandran’s final report of July 2011, the Supreme Court ordered the SIT to further investigate in the light of the Amicus Curiae’s contrary findings and thereafter file a final report in front of a Magistrate. The fact that the Supreme Court was not going to monitor investigations any more led Modi to claim his first clean chit even though the SIT’s final report had yet to be filed at this stage. So there was clearly no question of a clean chit from anyone at this stage. Moreover, the Supreme Court had also stated in the same order that in case the SIT decides in its final report not to prosecute someone, the Magistrate should hear Zakia before making a decision.

One clean and one not so clean chit

The conclusions drawn by the SIT in its final closure report filed on 8 February 2012 were not only different from those drawn by Ramachandran, but also from its own interim reports. In its watered down final report, the SIT concluded that there was not enough prosecutable evidence to bring charges against Modi. This led Modi and his supporters to make a new claim of having received a ‘clean chit’ by the SIT, a Supreme Court-appointed investigative body. True, but Ramachandran, who is also a court-appointed investigator, disagreed with the SIT’s conclusion. The most important point of difference was whether to believe the testimony of Bhatt, a serving police officer, who had stated that he was present at a meeting where Modi asked those present to permit Hindus to vent their anger. The SIT decided that Bhatt’s testimony was unreliable and that in its absence there was not enough prosecutable evidence against Modi. However, Ramachandran took the view that “it would not be correct to disbelieve Bhatt at this prima facie stage” and that Bhatt should be cross-examined in a trial to determine whether or not he was telling the truth.

It is worth noting here that both the SIT and the Amicus Curiae have only an advisory role—neither conveys the view of the Supreme Court. Had the SIT concluded that there was prosecutable evidence against Modi, it would not have meant that Modi was guilty; it would have merely made his prosecution more likely.

The case against Modi is ongoing

Zakia filed a protest petition against SIT’s clean chit in a Gujarat Magistrate’s Court, which decided on 26 December 2013 that the SIT had come to the right conclusion and that Modi should not be charge-sheeted. Once again, Modi and his supporters distorted the outcome to proclaim a third ‘clean chit’. On 18 March, Zakia approached the Gujarat High Court challenging the Ahmedabad Metropolitan court. This may yet lead to another ‘clean chit’ claim. Eventually the appeal will reach the Supreme Court, which will decide whether a case should go ahead under the existing criminal law in India.

And therein lies the rub. Under the existing criminal law in India, it is unlikely that Modi would be found guilty of any of the charges brought against him. Prevailing Indian Criminal Law requires proof that the accused carried out, or directly conspired to carry out, the crime. This is distinct from International Criminal Law, under which a head of state who could have prevented a crime, but chose not to, can be found guilty. In this context, Modi might have been better off if Zakia’s case had gone to the courts in the first instance—by now he might have had a truly clean chit.

Gautam Appa is Professor Emeritus at LSE.

In my view, the SC is not working honestly. It is prejudiced against certain people. The question is, if even one person dies, why isn’t the state govt, no matter which party is ruling, put to justice? A failed judiciary system.

Trials against politicians rarely come to fruition in India and even the few that do result in a slap on the wrist punishment (see: Lalu Yadav). The fact that UPA over the past decade has been unable to convict Modi of anything despite throwing all their resources into the case is enough for me. Besides, the alternative is Congress who purposefully massacred Sikhs in 1984 to avenge Indira Gandhi’s death, and since then have been the scourge of India.

It was a great article and great comments by some great people. Can you all give me direct answers for my questions.

1. Why did this disastrous incident take place?

2. What do you say about the death of innocent people who died on the train?

3. Why is the life of a Muslim or Christian or whatever religion important and the life of Hindu considered useless? When a Muslim or Christian is killed by a Hindu it is a very big issue, but when a Hindu is killed by a Muslim or Christian, it is not important. Is this the justice you people are speaking about?

Gautam Appa and company are basically the product of 60 years of the Left based education system so they cannot accept the fact that only because of the Hindu majority the so-called secularist and minority are still safe here. What is happening in other countries? Gautam and company never wrote an article about how Mr Jafri allegedly murdered the Karsewaks. Why in whole world there shouldn’t be any country which should have Hinduism as its RastraDharma? Actually Hindus are a very soft target, so anyone can target them.

And, you are basically either

a) self deluded into this quasi-nazi state of mind where the Hindu Right Wing is always in the right.

OR

b) lobotomised by India’s propagandist, pandering media financed by crony capitalists with clear, undeniable ties to the Gujarat government.

And, for the sake of argument, let’s assume that your claim about Jafri is true. Well, even then, is retribution befitting of a democracy? The individuals at the centre of the massacre belong to a party that is fighting elections harping on democratic accountability, but with such barbaric atrocities on it’s hands, can it really be taken seriously? Now, now, before you get excited, this is not an implicit defense of the Congress. They’re no better — I am fully aware of ’84 and the callous, inexcusable statements of a certain deceased PM.

Does the train incident justify killing of innocent human beings? People of our country should raise their voice against religious riots irrespective of their own religion instead of saying “the others” started it and “why should we always be the victims”. I condemn both the train incident and the riots post that. However the alleged complicity of the administration in the latter bothers me more. You may feel aggrieved by the killings of innocent Hindus in the train riots but do you think people from minority communities feel less aggrieved by the riots that happened after it which also lead to loss of innocent lives. It is humans who made religion, that they should let their own creation make them fight each other is a real tragedy.

Modi took all the steps to stop the riots by calling up army within 24 hours and he wrote to all the border state CMs belonging to Congress for additional force, but none of them responded positively. The fact that nearly 450 Hindus were killed by the security forces shows that there was no state complicity. Moreover it happened within three months of Modi taking over a state which is known for such riots. In the last 12 years there has not been a need for a Sec 144, leave alone a riot. Compare this with the attitude of Rajiv Gandhi during the 1984 riots with a big tree falls comment. These kind of efforts by the pseudo-secular forces will not yield any impact as the public is now aware of the real facts!

Modi’s speech at Becharaji in Gujarat – After the riots

Excerpts –

‘Do we go and run relief camps? Should we open child producing centres?

We want to firmly implement family planning. Hum Paanch, Humare Pachees (We five, our 25) (laughs). Who will benefit from this development? Is family planning not necessary in Gujarat? Where does religion come in its way? Where does community come in its way?

The population is rising in Gujarat, money isn’t reaching the poor? What’s the reason? If some people go on producing children, their children will fix cycle punctures only (Audience laughs).’

What are you trying to convey by this reply? Post 2002 riots, there have been no riots and BJP has won continuously even in places where muslim population are in majoriy. There is no discrimination based on Religion. If one does not go by the pseudo secular brigade’s false propaganda, they can see the over all development. The only state where true secularism is practiced is the state of Gujarat and the reason for that is its chief minister Shri Narendra Modi.

I am not sure which “International law” was the author referring to in the last paragraph. Such vague claims can undo the credibility of the article which so painstakingly the author has tried to put up. I am also not sure how Section 107 of the Indian Penal Code which talks about “Abetment to a thing” is ignored by the author while making the claim.

Its been 12 long years. And all these years the legal scrutiny that Modi had to undergo, am not sure any world leader has ever had to. And yet he is 100% conviction-free, and that ought to say something. Either the detractors have not been good in their homework – but this seems unlikely spanning over 12 years, or, Modi is just not guilty. I am in inclination to chose the latter.

Congress and BJP are the cause of rift between Hindus and Muslims .They pre plan everything and execute is smoothly just so the various religions communities end up fighting each other and they do this for gaining support from individual communities like the 2002 incident made Modi a hero for the Hindus . And we Indians still fail to see all this and follow blindly these corrupt leaders and when cases like babri masjid or the 2002 incident are brought up the people turn a blind eye / deaf ear towards them. Like a recent sting operation brought out that Advani and V K NARASIMHA RAO knew about the pre planning of babri masjid ….people were given training for it like they they do in the military. And now BJP is saying its a Congress sponsored conspiracy just to hide their own faces / avoid questions . After all this people continue to support such parties who are the actual conspirators.

Please stop lying here! Mr. Bhatt’s claims were found to be completely false, as his phone records showed that he was at a different location at the time he claims he was at the alleged meeting, SIT lists that. Stop misleading the people, please. Enough is enough!!

Logic does not apply here as it never applied in any riots, not only in India but world over. Rule is not by the people favouring people but for big corporates and when you talk of truth and logic, you are branded as Naxalites.

A very genuine article but how many people read this and how many voters do understand and vote for a “people’s party” which actually does not exist in most of the countries and most of the time?

Wish law as per true logic exists and implemented! Will the progressive forces rise?

The Supreme Court just quashed Sanjiv Bhatt’s plea, says attempt to influence court through politics and activism. Sanjiv Bhatt, the expelled ex-IPS officer, on whom the entire case against Prime Minister Narendra Modi for the latter’s alleged role in the 2002 riots and the hopes of many opposed to Modi rested, has been finally handed down a judicial invalidation from the country’s highest court. His theories were, really, just theories.