P.V. Narasimha Rao served as Prime Minister of India between 1991-95 and presided over the country’s economic liberalisation, yet his legacy is highly contested. In Half Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao transformed India political scientist Vinay Sitapati draws on new evidence and interviews to present an alternative portrait of one of India’s most misunderstood and maligned leaders in modern history. Abhilash Puljal finds the book is fast paced and lucid and writes that it is an informative read for both academics and non-academics who are unaware of the contributions made by Rao.

P.V. Narasimha Rao served as Prime Minister of India between 1991-95 and presided over the country’s economic liberalisation, yet his legacy is highly contested. In Half Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao transformed India political scientist Vinay Sitapati draws on new evidence and interviews to present an alternative portrait of one of India’s most misunderstood and maligned leaders in modern history. Abhilash Puljal finds the book is fast paced and lucid and writes that it is an informative read for both academics and non-academics who are unaware of the contributions made by Rao.

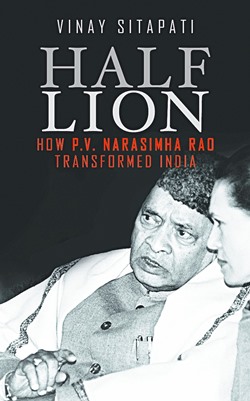

Half Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao transformed India. Vinay Sitapati. Penguin Books India. 2016

As the family of P.V. Narasimha Rao commemorated the former Prime Minister’s 95th birth anniversary and India marked 25 years of economic liberalisation; a young scholar, Vinay Sitapati, launched his debut book ‘Half Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Transformed India’.

As the family of P.V. Narasimha Rao commemorated the former Prime Minister’s 95th birth anniversary and India marked 25 years of economic liberalisation; a young scholar, Vinay Sitapati, launched his debut book ‘Half Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Transformed India’.

The book is a biography that gives Pamulaparthy Venkata Narasimha Rao his rightful place in the history of India as its ‘principal architect of economic reforms,’ and simultaneously challenges the view, propagated by the Indian National Congress (INC), that he was a conspirator in the Babri Masjid demolition. In twenty years since Rao’s retirement from active politics, the party which he served for six decades has been ‘determined to erase him from the party’s pantheon [by blaming him] for complicity in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, Union Carbide’s Warren Anderson escape after the Bhopal gas tragedy, and above all, for conspiring to demolish the Babri Masjid in 1992.’ Upon his death in 2004, the Congress party even denied Rao a funeral in Delhi, as ‘Soniaji [Gandhi] did not want… him to be seen as an all-India leader.’

This diligently researched book draws from over a hundred interviews conducted by the author, and from ‘never-before-seen’ personal diaries, handwritten notes and letters, which were shared by Rao’s family. These exclusive texts provided revelations of Rao’s personal struggles on India’s foreign policy and economy, the nuclear programme and Babri Masjid. The 391-page book is fast paced and lucid even for a novice of modern Indian history. The author conscientiously explains the background behind people, events and locations with their relevance to the commentary in the book.

The book traces Rao’s story through his years as an Andhra politician, his loyalty to the Nehru-Gandhi family, his stint as an inadvertent Prime Minister, his relationship with Sonia Gandhi, the destruction of Babri Masjid, India’s nuclear policy, his ‘humiliation in retirement’ and injustice post his death. However, it is not a tribute to Rao, but a critical assessment of an astute politician, a polyglot and an intellectual, who ‘reinvented India’s economy, international relations, internal security, welfare schemes, and the nuclear programme.’ Sitapati ranks Rao with ‘revolutionary figures’ such as Jawaharlal Nehru, Deng Xiaoping, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Charles de Gaulle. But he also makes it clear that Rao was not a mass leader; he presided over a minority government in the Parliament; his party colleagues distrusted him and the Gandhi family kept an eagle eye on him. A ‘few world leaders have achieved so much with so little power.’

Architect of India’s economic reforms

Rao emerges as a man who provided transformational leadership to India at a time of deep financial crisis. The Congress party has assiduously given credit for the 1991 reforms to Dr Manmohan Singh, Rao’s finance minister and to Rajiv Gandhi, a former prime minister from the Nehru-Gandhi family. However, the author provides key insights and ‘behind-the-scenes details of how Rao neutralised criticism to the radical economic reforms both from sections of the opposition and from within his own party.’

21 June to 24 July 1991 witnessed a revolution in India’s economic policy, born out of a financial crisis that had been some years in the making. ‘I didn’t know it was this bad…’ was Rao’s reaction to the briefing on the balance of payments crisis, the unprecedented devaluation of the rupee and the mortgaging of gold bullion, when being updated by his cabinet secretary; a day before he was to be sworn-in as India’s tenth prime minister. ‘The economy was so wrecked that India was pawning its family jewellery. There have been crises in 1965-67, 1973-75 and 1979-81. None, however, was more alarming than what India faced in 1991.’ To mend the situation, India needed ‘fiscal discipline, dismantle trade barriers, and remove licenses, permits and anti-monopoly laws that bound domestic entrepreneurs.’

By the time Rao understood the gravity of the situation, a formerly ‘protectionist Rao had given way to the pragmatic Rao.’ He handpicked experts, ‘regardless of their political affiliations’, and sought advice from them. Interestingly, while deciding on his new ministerial cabinet, Rao, ‘wanted an apolitical economist with an internationally credible face capable of dealing with the west’ and was offered two names – Professor I.G. Patel, former Director of the London School of Economics, and Dr Manmohan Singh, Economist and former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. Patel declined the job so Dr Singh was sworn in as finance minister.

Earlier governments, led by Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi and V.P. Singh, also were aware of the significance of liberalising the economy. Rajiv Gandhi had even attempted such reforms in 1985 but he ‘lacked the skills to manage the politics of reform.’ In pulling off the reforms his predecessors had failed to implement, Rao proved to be a shrewd strategist. Sitapati writes, ‘though Manmohan was critical to Rao’s team, he was not indispensable. Had I.G. Patel become finance minister in 1991, liberalisation would have likely persisted. But had Narasimha Rao not become prime minister, India would have been a different country.’

Babri mosque demolition

The Babri Masjid was a mosque built in the sixteenth century in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh on the orders of the Mughal emperor Babur. Some Hindus claim that the Mughals destroyed the structure marking the birthplace of the Hindu deity Ram, in order to build the mosque. This political, historical and socio-religious debate over the history of the site has led to several conflicts and court disputes between Hindus and Muslims. On 6 December 1992, over 100,000 radical Hindu nationalists demolished the Babri Masjid triggering violence across India, which resulted in around 2,000 deaths.

Many consider Rao’s role in the Babri Masjid demolition to be the darkest time of his tenure as prime minister. They accuse him of being a conspirator by deliberately not acting to stop the demolition of the mosque that December. Sitapati makes good of his training as a lawyer to delve into the legal constructs of the Indian constitution alongside gathering evidence and concluded that “history has judged Narasimha Rao harshly’. He writes that, in the lead up to 6 December, the only option Rao had was to impose President’s rule, but he could not even do this because members of both his own party and the opposition were against it. The Supreme Court refused to give Rao a receivership and the Governor suggested that president’s rule should not be imposed.

‘If he had still pushed for president’s rule under those circumstances, the opposition Bharatiya Janata Party would have pushed for a no-confidence motion in the Parliament and the matter would have gone to the Supreme Court. It would well have been held illegal, and Rao running a minority government could have lost his job.’

Narasimha Rao, who had a very high opinion of himself as a Hindu leader (before returning to Delhi when he was called to take on the mantle as leader of the Congress party and prime minister, Rao was contemplating on taking on the offer from Cortallam monastery as their head monk), thought he could out-manoeuvre Hindu saints, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Rashtriya Svayamsevak Sangh leaders and convince them to protect the mosque without having to impose President’s rule.

He was, however, mistaken and his actions during the crisis led political rivals like Arjun Singh to level charges against Rao of being incommunicado or was performing puja (religious rituals) or even sleeping during the destruction of the Babri mosque in their biographies and memoirs. Sitapati dismisses all of these as either conspiracy theories, largely floated by the Congress party, or outright lies.

Misunderstood and maligned leader

The book is a portrait of one of India’s most misunderstood and maligned leaders in modern history. On occasion, the book may seem overly appreciative, but is certainly no hagiography. Sitapati, elucidates how Rao used the Intelligence Bureau (IB) to spy on his colleagues, including Sonia Gandhi; importantly he stresses on Rao’s failure as the home minister in 1984, ceding authority to the Prime Minister’s Office under Rajiv Gandhi during the anti-Sikh riots, in the wake of Indira Gandhi’s assassination – he calls it Rao’s ‘vilest hour.’

During and after his term as prime minister, Rao was accused of corruption by Lakhubhai Pathak and Harshad Mehta; for forgery in the St Kitts First Trust Corporation Bank case; and for bribing the members of Parliament of the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha party. Rao was acquitted in all these cases. The book does comment, but does not delve much into these incidents leaving the reader wanting to know more. Furthermore, comments and reflections of M. S. Bitta, the ‘Punjab Congressman side lined for his proximity to Rao’ and R.K. Anand, Rao’s Lawyer – both who have been mentioned in the book – would have been noteworthy; besides that, of Deepak Bhojwani, a foreign service officer – not referred anywhere in the book – who served as private secretary to the prime minister between 1994 and 1996.

In writing this book the author has opened the Pandora’s box, which I hope will lead to further scholarship on understanding not just the man himself, but also the impact of his interventions that led India into the global economy, impacted its international relations, its nuclear programme and improved contribution to the welfare state among others. These require independent in-depth study. It is also an informative book for a broader non-academic readership who are unaware of the contributions made by Rao, especially the post-liberalisation generation, who continue to credit Dr Manmohan Singh, as the principal architect of India’s economic reforms and nuclear programme and defaming Rao as a corrupt politician and a conspirator during the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

In the words of political writer Kapil Kommireddi, ‘if Jawaharlal Nehru ‘discovered’ India, it can reasonably be said that P.V. Narasimha Rao reinvented it.’

Cover image credit: C. Srinivasulu CC SA 4.0

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Abhilash Puljal is an independent consultant with expertise in private sector development strategy and MSME development, currently advising the Government of Bihar through PricewaterhouseCoopers on a DFID funded project – “GROW Bihar.” Alongside, he is also advising in the implementation of “Supporting Indian trade and investment for Africa” (SITA) project for the International Trade Centre, Geneva, also funded by DFID, in Rwanda and Ethiopia.

Abhilash Puljal is an independent consultant with expertise in private sector development strategy and MSME development, currently advising the Government of Bihar through PricewaterhouseCoopers on a DFID funded project – “GROW Bihar.” Alongside, he is also advising in the implementation of “Supporting Indian trade and investment for Africa” (SITA) project for the International Trade Centre, Geneva, also funded by DFID, in Rwanda and Ethiopia.

He is also the Regional Ambassador of the LSE Alumni Association for South Asia. He can be reached at abhilash.puljal@gmail.com.

I have started reading the book, HALF -LION , half completed. Read your review , and I must admit that your observations are very apt and interesting insights into the book are made available.