Tommaso Amico di Meane looks back on his experiences in Varanasi and reflects on the involvement of young people in the Lok Sabha elections.

Walking along the Ganges River for the first time was like visiting an outdoor cathedral hundreds of meters long. The people lining the banks interacted with the sacred waterway in their own manner: some meditated on the banks, others used it for washing and purification purposes while children played and enjoyed themselves with the vivacity typical of their age. The Ganga is not static as other sanctuaries or religious symbols, rather, it is alive, changing colour and even mood as it flows.

I was in Varanasi (or Benares) to follow the last phase of India’s great elections. Chance decided that the city “older than history” (Mark Twain) would be the site of the last duel of the 2014 Indian Lok Sabha elections. On the Ganges rivers “David”, Arvind Kejriwal (Aam Aadmi Party) contested the seat of “Goliath”, Narendra Modi (Bharatiya Janata Party). The temperature – already around 45°C – further climbed after the unexpected Rahul Gandhi (Congress Party) “revenge” roadshow in Varanasi. This was launched after Modi broke the unwritten agreement of not campaigning directly within a rival’s constituency and staged a rally in the historical Nehru-Gandhi seat of Amethi in Uttar Pradesh. The atmosphere was vibrant as the eyes of India turned to focus on Varanasi once more.

Another thing clearly noticeable in the streets was the involvement of young people. Wearing political party caps or Electoral Commission badges, they campaigned, discussed and organised, participating proudly in India’s huge democratic machine. This was a confirmation of what I had already sensed working with students of many universities across the country as part of my research: the young generation appears to have developed a new democratic awareness, aspiring to change and believing it can be achieved through their participation in elections.

India’s first time voters numbered more than 100 million in this election, but the most interesting aspect is perhaps not the quantity but the quality of their participation. This is in part a result of independent choices made by the younger generation, but it is also due to the efforts made by national institutions to raise the profile of politics among young people over the last decade. Discussions about India’s democracy have sprung up everywhere: on talk shows, radio programs, theatres and at sporting events. The Electoral Commission organised quiz and writing competitions involving hundreds of schools and universities to encourage engagement with elections. January 25 has been dedicated as National Voters’ Day since 2010 in order to promote political participation among young people. The response has been amazing and estimates say that participation among 18-19 year old Indians has rocketed from 10% to 45% over the last two years (see S. Y. Quraishi, 2014 An Undocumented Wonder, 2014, Rupa Publications).

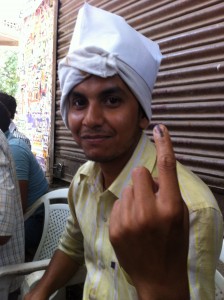

As a result, millions of young Indians have started to ask questions, discuss and explore, in person and online. “Having a political awareness and ideas is becoming cool among new generations” explained a young Indian journalist and a friend of mine. She showed me a Facebook page with dozens of “selfies” by her friends proudly showing the violet ink mark applied to their index fingers after voting. Universities are also playing a significant role in encouraging youth engagement, where professors and intellectuals play a role in effectively stimulating the students’ critical thinking.

Despite the challenges facing India, the opportunities available to the youth of India are on average consistently higher than their parents. One evening during my stay in Delhi I dined with the family of Amritt, the caretaker of the guest house in which I was staying. During the dinner I sat next to his son, a brilliant 23-year old student studying for a Masters in Law and hoping to do a PhD in the United States, before returning home to contribute to his country.

Amritt’s son is just one of the faces of the brighter future India imagines. He has a global outlook but he remains proud to be Indian and wants to help build a better country. Amritt’s son has been able to take advantage of the new opportunities available to his generation so he does not have to do the same work as his father. The question now is what can politics in general (and the new government in particular) actually offer him? Electoral campaigns and discussions have been rather rhetorical on this point. The manifestos of major political parties promised “more jobs” for young people, but they failed to specify any concrete measures and policies. After having been involved so intensely (and mostly as volunteers) by both institutions and political parties during the election, young people now want to see concrete steps forward. How are the new jobs going to be created for them? How will young people be included in political agenda of the new government? The next step of harnessing this democratic awareness will be closely linked to how far young people are able to participate in and change the system.

This process is irreversible and has been formalised during this election with the massive participation of young, furthermore encouraged by the official entry of India within the “democracies 2.0” of new and social media. There is no risk of any sort of traumatic “India’s springs” across this process, young Indians inherited a democratic DNA. However the political offer and its composition need to be adapted. This change is necessary and pressing: 1/2 of India’s population is under 25 years of age, they want to be included, to participate, to be heard and more widely, they want a country more like them.

All images are the author’s own.

About the Author

Tommaso Amico di Meane is a PhD student in Political Science at the Seconda Università di Napoli (SUN). He was Visiting researcher at the Indian Law Institute (ILI) of New Delhi during the 2014 elections.

thoroughly and beautifully covered.. the entire political structure of Indian system. a very hard job to work in the extremely harsh climate and come up with something worth mentioning. though not Indian his work appears as if an Indian has taken note of the entire political setup of the country post election.