The huge number of security forces stationed around the world as United Nations peace keepers is second only to the global military deployments of the USA. But most UN peacekeepers come from the emerging powers and developing states that comprise the global South. A major contribution of Legions of Peace is its critical review of UN peacekeeping, which rejects any blind, religious like faith in such a system. The analysis of contemporary peacekeeping operations is backed up by rich material, which brilliantly answers the research question with strong and concise arguments, writes Shuo Liu.

This post originally appeared on LSE Review of Books.

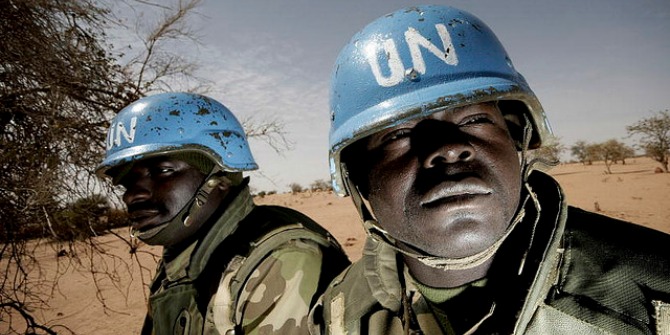

As of 31 May 2014, there are 122 countries contributing to the UN peacekeeping operations. Interestingly, the top ten are all developing countries, with the top three contributors being Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. This phenomenon of the global South constituting the major source of soldiery to the blue helmets is featured in Philip Cunliffe’s new book, in which a critical constitutive explanation is given for why the Southern countries supply most of the UN peacekeepers. The research question is addressed through analysing the post-Cold War international context in which the Southern states exist (Part I) and the motivations behind the Southern states’ commitment (Part II).

Contrary to the common belief that the cosmopolitan UN peacekeeping is anti-imperial, the author argues that UN peacekeeping actually represents the “highest form of liberal imperialism” (Chapter 3). Peacekeepers from the global South are important players in securing the imperial interests of our time (Chapter 4) and they form a new generation of ‘sepoy’ recruits from Indian forces and ‘askari’ recruits African colonial forces who enhance the legitimacy, expand the resources, and reduce the risks and costs of peacekeeping (Chapter 5). Subsequently,the author argues that the UN peacekeeping institutions are essentially serving the security concerns of the powerful global North (Chapter 6), and it can be seen as an imperial multilateral system, in which the Southern countries are successfully incorporated (Part III).

If liberal imperialism of UN peacekeeping is accepted, how to account for the oppressed Southern countries as a whole helping to construct the imperial security rather than trying to undermine this system? In chapter four, by including both states and empires as political actors, through a thorough historical examination and comparison, the author proposes that today’s UN peacekeepers from the South should be viewed as a continuity of former colonial deployment in imperial defence. For example, the newly independent Southern countries’ armed forces are subject to the priorities of the powerful North, which Cunliffe calls “dependent militarisation” (p.122, pp.155-158); some of the colonial armies who have previously participated in imperial warfare (e.g. Nigeria, India) quickly shifted into their new role as peacekeepers (pp.146-150); and moreover, despite the inclusion, they are still living in a Western dominated power structure, in which their involvement is crucial to not only legitimising UN peacekeeping, but also sustaining the imperial security with a much lower cost.

Still, at the individual state’s level, why do the developing countries of the South opt to participate the UN peacekeeping? The assumption of mercenarism is challenged at the opening of chapter five, examples such as Bangladesh show that earnings from UN peacekeeping is not as significant as it is believed to be. The national interests and sub-state motivations, however, seem to be more convincing explanations for participation. For instance, non-materialistic gains such as on-the-job training, exposure to war zones, experience of international deployment, the improvement of international reputation and legitimacy, and competing for regional leadership are all appealing factors of UN peacekeeping to developing countries.

Specifically, a sketch of the BRIC countries’ peacekeeping diplomacy is provided. By looking into the motivations and actual behaviours of each of the four rising powers, the assumption that these powers would perhaps reshape the existing order is overturned. The BRIC countries generally lack the institutional infrastructure and have to rely on the UN to provide the stage “on which these powers can test out geopolitical expansion” which in turn demonstrates the “proximate limits of their nascent power” (p.201).

Alarmingly, by pointing out the counter-examples of the democratic peacekeeping theory such as Fijian’s series of coups in the 1980s and Bangladesh’s fifteen years of democratic rule suspension, the author warns us of the peacekeeping praetorianism: “it is not possible to elevate the security institutions of the state without feedback effects on the democratic polity” (p.212). This makes us think twice about the UN Under-Secretary-General Hervé Ladsous’s remark on 17 June 2014, in which he identified six critical priorities to strengthen peacekeeping, among which “expand the base of major contributors to peacekeeping while deepening the engagement of current contributors”was listed as the first one.

A major contribution of this book is its critical review of UN peacekeeping, which rejects any blind, religious like faith in such a system. The analysis of contemporary peacekeeping operations is backed up by rich material, which brilliantly answers the research question with strong and concise arguments. For this reason, the book serves as a good read to anyone who works in the area of international relations, peace studies or international law. In addition, as Philip C.C. Huang correctly points out, “twentieth-century revolutions against Western imperialism drew their guidance not from the ideologies and theories of indigenous traditions but from the alien West”. Therefore, for the readers from the global South, I suggest while we actively engage in the theoretical discussion of this book, we shall also endeavour to explore theoretical underpinnings against imperialism from our own distinct traditions.

——————————————

Shuo Liu (LL.B, LL.M) is a PhD candidate in the School of Law at University College Dublin. Her PhD research explores the evolution of refugee law and protection in the People’s Republic of China. She has taught on Chinese politics and governance with a focus on legal issues. Her interests include refugee law, international human rights law, socio-legal studies, Chinese law and legal anthropology. Read more reviews by Shuo.