In a new study published by The Centre for Internet and Society in Bangalore, P.P. Sneha offers a detailed mapping of digital practices in arts and humanities scholarship in India. In this article, she summarises the value of conducting such a mapping in the Indian context and explores the implications of digital approaches and innovations for research and practice in humanities.

In a new study published by The Centre for Internet and Society in Bangalore, P.P. Sneha offers a detailed mapping of digital practices in arts and humanities scholarship in India. In this article, she summarises the value of conducting such a mapping in the Indian context and explores the implications of digital approaches and innovations for research and practice in humanities.

Global narratives around the term ‘digital humanities’ (DH) reference a predominantly Anglo-American history in the field of humanities computing. While the use of computational tools in humanities work is not new, the availability now of a large body of cultural artifacts post the digital turn, as well as emergence of new kinds of digital objects has opened up several possibilities for humanities research, practice and pedagogy using computational approaches. It also asks questions about the scope, context and methods of such forms of inquiry, as the field itself spans several disciplines, as well as creative practices outside academia.

While there is enthusiasm about the immense interdisciplinary potential offered by DH, there has also been significant criticism. Most early attempts at contextualising the field have been located within a ‘narrative of crisis’, of the humanities in particular, and higher education in general. However, this again seems to emerge from a specific neoliberal imagination of higher education and the university system in the West, specifically the US, which may not necessarily find resonance elsewhere. As several critics of the ‘big-tent’ of DH have pointed out, there has been a need to locate alternative narratives of DH – which also reflect more global contexts of the ‘digital’ and how the humanities engage with it. While there is work now in DH emerging from countries in the “Global South,” notably India and China, there is also an interest in rethinking discourse around the field to understand and address better the questions that may emerge from doing DH in these spaces. This is an important exercise in contextualisation of debates around the digital as well – where conditions of access and usage, transition from analogue to the digital, and the notion of ‘digitality’ itself need to be defined better.

In India, several strands have been developing over the last five years. Five universities now offer various programmes in DH in India, ranging from a Master’s degree to certificate courses, and there have been several workshops, winter schools, seminars and one national level consultation. The areas of work range from digital archives, game studies, textual studies, design and cultural heritage to name just a few. While these have managed to initiate interest in DH, there is still a lack of consensus on what exactly constitutes the field in India, as questions around definition, ontology and method remain. One of the early instances of DH practice has been an online variorum of Rabindranath Tagore’s works titled Bichitra, developed at the School of Cultural Texts and Records (SCTR), Jadavpur University. This variorum also has a unique collation software, titled Prabhed (‘difference’ in Bengali) that helps to assemble text at three levels (a) chapter in novel, act/scene in drama, canto in poem; (b) paragraph in novel or other prose, speech in drama, stanza in poem; (c) individual words, thus helping trace variations across different editions.

The variorum is a good example of understanding changes in cultural artifacts, textuality, reading and writing practices with the digital turn. The text itself as an object of enquiry undergoes changes to become available for study on a digital platform, where it is now possible to search across a large corpus of texts for minute changes in words or sentences, and ask questions of these in terms of their usage, instances and contexts of their occurrence, thus facilitating a kind of enquiry previously never undertaken in textual studies. The growth of such cultural repositories has informed some of the early debates on DH in India. In fact, as Professor Amlan Dasgupta, also at the SCTR, says, we are “living in an archival moment”, where it is possible now to create such a corpora due digital technologies, which also creates new objects and methods of study.

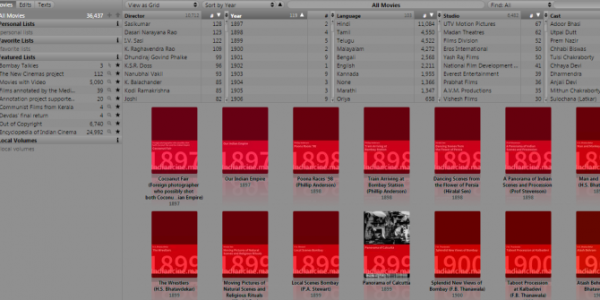

Pad.ma and Indiancine.ma are two examples of online archives which allow the user access to an array of material, but also add to them through annotations and referencing. This is done through the addition of transcripts, descriptions, events, keywords; annotations in the form of commentary and marginalia, as well as paraphernalia around the film object such as posters, images, lobby cards, advertisements etc. The materials can be re-contextualised by the reader in different ways; layering the primary text with annotations also produces a new research object, or text that then necessitates new methods of textual analysis as well. What these also encourage are collaborative forms of research and practice, often drawing together people and methods from diverse disciplines and creative practices. Sebastian Lutgert and Jan Gerber, media artists and programmers who have worked with a larger team on developing both these archives reiterate this when they describe the digital archive not only a tool or space of publication for humanities researchers, but is also a software project, a resource for a film fan club and so on as it is open to interpretation. In their work with people from both the humanities and sciences, they do see a void between domains, and reiterate that it is very difficult for people to have a conversation across their disciplinary moorings. The development of tools and methods, and exploration of the computational possibilities of digital archives then will need to be through interdisciplinary and collaborative methods.

The changes in the archival object are also important, as pointed out by Professor Indira Chowdhury, historian and Founder-Director of the Centre for Public History (CPH) at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. There is now a diversity in the mode of documentation due to digitisation, which urges us to think about issues such as format and the problems of planned obsolescence. The role and modes of curation are also extremely important in making archives public and accessible, even as concerns about privacy and copyright persist.

The implications of these changes for research and practice in humanities are many, and are chiefly seen in the growth of new forms and methods of enquiry. Digitisation significantly alters the cultural artifact, and there is a need to understand and theorise this digital object better. As Padmini Ray Murray, faculty member at Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology points out, the digital is one way to mediate the material object, particularly those that are not textual, since that kind of experiential access can only be provided by the digital, especially in the case of archival objects. Rethinking the role of technology in the classroom, in curricula and resources, and working towards a digital pedagogy would be key challenges here. The development of courses on DH in universities in India, and the manner in which the field is being curricularised, would be an indication of its specific academic concerns in the Indian context, and the disciplinary challenges and questions that it may throw up for the teaching-learning process.

Exploring the field of DH provides several learnings about the digital or media landscape we presently inhabit, as well and insights into some of the challenges and possibilities of doing and studying DH in India. The discourse in India is still located largely within an academic space, and questions about disciplinary and pedagogical frameworks and methodologies remain pertinent. The digital turn has led to rethinking the role of technology, particularly internet, in teaching and learning practices, both within and outside the classroom; this is also indicative of larger changes in the university system in India. With the growth of work in areas such as design, critical making, art and cultural heritage, there is also scope for collaborative work now across different domains of expertise. Contextualisation of these changes is important, given that DH, or engagements with humanities-after-digital and/or with digital-through-humanities come out of a different chequered history of humanities and technology in India. Access, and more importantly conditions of access to the internet and digital technologies remain important factors, especially in the Indian context, where apart from a digital divide, familiarity and accessibility of certain digital platforms and tools as well as the lack of shared, collaborative digital infrastructures, whether in terms of tools, software or labour are important factors.

In the case of archival work, which is of significant interest to DH work in India, there are specific challenges in terms storage and preservation of materials, cross-referencing and meta-data standards, conditions and structures of access, roles and forms of curation, re-usage of archival materials in research and pedagogy, and the constraints to digitisation of archival materials, particularly in terms of rare materials and those in Indian languages. As illustrated by some of the examples above, the process of digitisation itself needs to be understood more comprehensively, especially in the way it changes objects and methods of enquiry. These then urge a rethinking of processes such as interpretation and representation, which are central to the humanities.

The full paper can be accessed and downloaded from the CIS website here.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Puthiya Purayil Sneha is a Programme Officer at the Centre for Internet and Society, India. This post draws from a study on mapping conversations in the field of digital humanities in India. She can be reached at sneha[@]cis-india.org

Puthiya Purayil Sneha is a Programme Officer at the Centre for Internet and Society, India. This post draws from a study on mapping conversations in the field of digital humanities in India. She can be reached at sneha[@]cis-india.org