It has been 20 years since local elections were held in Nepal, and as a result a whole generation of young people have been deprived of their right to exercise their citizenship in this context. In this article, Thaneshwar Bhusal welcomes the government’s recent announcement that local elections will be held in May, while also outlining key challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

It has been 20 years since local elections were held in Nepal, and as a result a whole generation of young people have been deprived of their right to exercise their citizenship in this context. In this article, Thaneshwar Bhusal welcomes the government’s recent announcement that local elections will be held in May, while also outlining key challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

On the 16 May 2016, I published a piece on this blog, expressing frustrations on the fate of local democracy in Nepal. The article stressed that in absence of local elections, Nepal’s quest to stabilise democracy had been severely disrupted, and thus, the country was struggling with a severe democratic deficit. On the 20 February, the government of Nepal declared local elections to be held on the 14 May for the first time in almost two decades.

News houses and social media users have expressed their approval, hoping that the move will be instrumental in stabilising the federal political system in the country. Political parties, civil society activists, and local democracy campaigners have also welcomed the news, though a small fraction of Madhesi political parties have immediately indicated they would not participate.

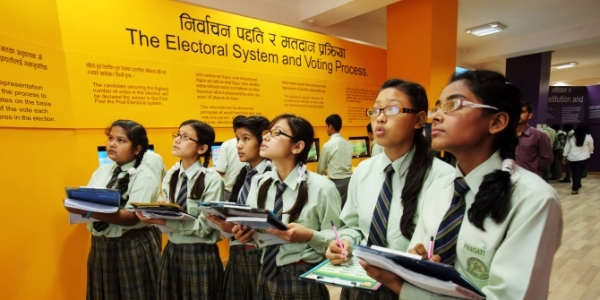

Generally, elections are regarded as key instruments of democracy. But Nepal’s upcoming local elections have special meaning in the context of its fragile political circumstances. This will be the first time for those who born since 1980 will have the chance to vote in a local election. This indicates that this election will be the first opportunity for about 25% of the 14 million estimated voters. It will therefore be historic to voters of the age group between 18 and 39.

Second, the elections are going to be held for local governments – not local bodies. This is the first time in Nepal’s political history that the constitution has envisioned local governments. The Local Bodies Restructuring Commission has recommended that a total of 719 local governments (462 villages and 257 municipalities) should be in the country, significantly less than the number of local bodies in 1997 (3915 villages and 57 municipalities). The amalgamation of local bodies has shrunk the number of local governments based on a range of criteria, including financial strength, population density, and geographic area. The new local level structures will enjoy constitutionally guaranteed roles and responsibilities, as opposed to the mere service delivery functions that have been carried out by local bodies for decades.

Third, the electoral process has been further refined, mainly to promote inclusive democracy. A total of about 34,000 representatives will be elected based on the first-past-the-post system of election but there are several new features. For example, there must be a woman representative in the post of either chairman or vice-chairman (in villages) and mayor or deputy-mayor (in municipalities). In each of the ward committees, at least two women will be elected along with a woman representative from Dalit and minority communities. There will be a total of 6,553 ward committees across all local governments, with 5 to 21 wards in a local government. This indicates the ambition to develop women political leaders in Nepal.

Finally, local elections mark the beginning of a series of other elections that must be carried out by the first week of February 2018. The prevailing constitutional provisions state that the central government must held elections at state and federal level within that time frame, as part of institutionalising federalism in the country. Hence, the declaration of local elections signals the government’s commitment, and thus increased hopes of people that more elections will be held for other new yet important federal bodies.

There are also challenges ahead. For the government, this will be to create an environment in which Madhesi political parties participate in the electoral competition. They have been demanding to reform some of the constitutional provisions, particularly in relation to state borders and names. If they continue to oppose the upcoming local elections, it could disrupt elections further down the line as well.

For political parties, the challenge is to communicate the notion of federalism as people exercise their citizenship through balloting for local governments. People need to know the difference between the older forms of local bodies (Village Development Committees, Municipalities, and Districts) and new local governments. Since local governments will have legislative, judicial, and executive functions to an unprecedented scale, it is the role of the political parties to communicate these distinctions. Failing to deliver such message will certainly weaken voter’s ability to make informed decisions. Moreover, further reforms to institutionalise federalism will depend upon how effectively political communication happens during the forthcoming local election campaigns.

The Election Commission of Nepal also reportedly faces challenges in conducting local elections. The commissioners requested at least 120 days preparation time, but the government’s announcement came only 83 days before election day. The government still needs to finalise the number of local governments in State 2, where Madhesi political parties have expressed their dissatisfaction. The Commission is said to be having difficulties in fixing polling stations considering the changed structure of local governance. Other challenges include the printing of ballot papers, deployment of election staff, and transporting materials in such a short time period.

Once in power, the newly elected local authorities will face more challenges. The prevailing Local Self Governance Act (1999) is not only irrelevant in the context of federal Nepal, but also insufficient to exercise the functions stipulated in the constitution. Although the prospective local governments’ will inherit many of the functions that have been carried out by local bodies, the difficulty lies in transforming the notion of local governance from an administrative agency to political entity.

Managing human resources has emerged as another challenge for local governments. As per the Clause (302) of the constitution, the government has been preparing to adjust all the civil servants who have been working for local bodies and central government agencies. But civil servants are putting pressure on the government to have ‘respectable integration’ into new structures. The challenge is to address the demands of existing staff while maintaining the rights of local governments. What if local government refuse to accept staff deployed by the federal government?

If elections are the backbone of any democracy, the forthcoming local elections in Nepal are significant in enhancing the quality of local democracy in Nepal. Several aspects of quality of democracy are assumed to be restored – right of ordinary people to exercise their citizenry, development of democratic leadership, enhancement and institutionalisation of accountable and transparent local governance processes, among several others. These aspects will help replace the ongoing elitist politics with a kind of leadership that is built from at the bottom of the society.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Thaneshwar Bhusal is a 3rd year PhD Student at the Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra, Australia. His research examines Nepal’s local governance in terms of how citizens have been participating in local decision-making during the absence of elected authorities in power (2002-2016). His study is funded by the Australian government through its Australia Awards Scholarship program.

Thaneshwar Bhusal is a 3rd year PhD Student at the Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra, Australia. His research examines Nepal’s local governance in terms of how citizens have been participating in local decision-making during the absence of elected authorities in power (2002-2016). His study is funded by the Australian government through its Australia Awards Scholarship program.