Professor Anirudh Krishna joined academics and students at the London School of Economics in a workshop organised by LSE South Asia Centre. The workshop, examining key themes of Krishna’s latest book Broken Ladder: The Paradox and Potential of India’s One Billion, provided a platform to exchange ideas on potential solutions and strategies to address the mass poverty experienced by millions across India, Rebecca Bowers reports.

Drawing on national data, Broken Ladder features accounts of individuals and grassroots research from 200 villages and 100 urban slums. It questions why, despite considerable economic growth, upward mobility remains elusive for so many. Krishna proposes possible policy suggestions – with the caveat that there should be no overarching policy approach due to the complexity of individual experiences and heterogeneity across states. Krishna concludes any meaningful development projects must be informed by a ‘worm’s eye view’ from the ground up.

Discussing inequality in India

Despite India’s economic growth, Krishna says that for the poorest, little has changed: ‘you see people earning their livelihoods in the same manner as they used to earn them a generation or two generations ago’. To illustrate this, Krishna draws on data highlighting the inequality of India in comparison to rest of the world, ‘You have at the same time as people in the millions who are poorest as the poor in Sub Saharan Africa… people who are as rich than the richest in the US and the West’.

Krishna discusses the dollar versus rupee economy, whereby certain items such as a Starbucks coffee, cost the same as they would in the West, and can thus only be purchased by an elite few earning a higher income, next to those who buy their coffee from the roadside for 10 rupees. This, Krishna claims creates complications for public policy – to balance the demands of the poor who want flush toilets and housing with the demands of the rich and the super-rich who want super highways.

There are multi-stranded explanations for the high levels of inequality in India. One of these is the rural/urban divide. Surveys have illustrated household possessions and income noticeably decrease in smaller towns and villages and this only grows as distance increases. One of the reasons for this is the growing crisis in agriculture – around 75% of landholdings today are of an uneconomic size for livelihood yet alone to feed a family. This contributes to the growing trend of labour migration, between 100 – 175 million people are estimated to be what Jan Breman has referred to as ‘nowhere people’.

Education in rural areas is also an issue. For those educated in village schools, chances of receiving a high paying job are low – with many becoming construction workers in the millions, Krishna claims. Only 2-9% from rural areas are in engineering colleges, and only 6% of students in business schools have less educated parents, which highlights the continuation of unbroken cycles of inequality. Furthermore, Krishna acknowledges the role of gender discrimination, noting the feminisation of agriculture and observing that for rural, less educated women, prospects are substantially lower.

Citing his research from villages in Andhra and Karnataka, including 10 years of surveys, Krishna notes the highest earning positions achieved by children were soldiers, police, or teachers. Most 14-22 years olds surveyed chose the above options as aspirational positions because alternatives such as corporate jobs were not visible or viable. Urban children however, were found to have different aspirations including civil service and software engineering. As a result, there is a huge untapped pool of talent, Krishna argues, claiming ‘if one makes the not unreasonable assumption that talent is randomly assigned at birth then a large section of the population is under-utilised’.

Another concern is ‘the assumption is that urban is the face of the future’ according to Krishna, when contrary to this narrative, the 2001 -2011 census illustrates a 71-69% decline in urban growth, but urban areas remain prioritised in resource distributioN. However, when people settle in urban areas they experience limited (if any) upward mobility. In Bangalore for instance, there aren’t children studying to be doctors or lawyers. In the better-off slums, children can home to become sales people or secretaries if they have completed high school, Krishna adds. The largest increases in employment have not been in software or call centres but industries such as construction, where the number of workers increased from 15 million to 20 million.

Finally, Krishna claims that the agenda of political parties has been captured by dollar income people. The people at the top have little idea of everyday life at ground-level and people at the bottom get hugely frustrated because they are asked to do things not applicable on the ground where conditions vary hugely. The very machinery that should be dealing with these problems is structurally incapacitated to deal with them. equalising of egalitarian opportunity policies are not in place because those who make these policies are part of the same value systems and structures.

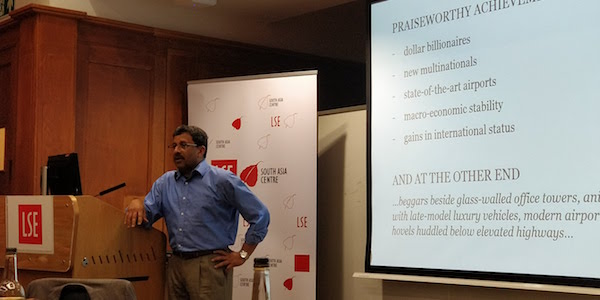

Professor Anirudh Krishna presents his findings at the workshop. Photo credit: Mahima A Jain, LSE South Asia Centre.

Solutions and policy suggestions

The solutions countries which industrialised many years ago utilised to address inequality are no longer available and the probability of creating productive jobs in large numbers is small, as the growth of the construction industry illustrates. It is best not to invest in nation-wide innovations which may cause a large loss to people but look to the grass roots level – as China transformed its rural health care system. From the discussion arose the consensus that India and countries like it need to recognise that their solutions should be homegrown and they need to invest in processes of multi stakeholder innovation.

- Universal basic income should not be the only solution but it can be a vector of these things (Maitreesh Ghatak)

- We must take advantage of local information and empower state capacity to make effective decisions rather than hierarchical ones.

- The future lies in creating job creators and not so much in relying on the existing job creators to create jobs eg India or the UK and the gig economy

- What we need to be doing is satisfying rather than maximising – there can be six solutions that solve the same problem effectively but it doesn’t mean that any one is the best for all.

- It is important to consider villages where things ’seem to work and things don’t seem to work which are not fundamentally different but then where things are very different’ Ghatak concludes, such as collective action and grass roots governance structure.

- Outcomes tend to be better where the latter are present in villages versus ones where this aspect is broken and does not seem to work so well – this Ghatak maintains, is a compelling hypothesis we should keep in our head when we approach some of these policy discussions.

(L-R) Professor Anirudh Krishna, Dr Mukulika Banerjee, Professor Maitreesh Ghatak, Dr Sohini Kar. Photo credit: Mahima A Jain, LSE South Asia Centre.

Discussion with Professors Sohini Kar and Maitreesh Ghatak (LSE)

Following Professor Krishna’s presentation, LSE staff Dr Sohini Kar (International Development) and Professor Maitreesh Ghatak (Economics) provided their insights into Professor Krishna’s book and the wider discussion of poverty in India.

Dr Sohini Kar

- Dr Sohini Kar described Broken Ladder as ‘timely and prophetic reading’ offering theoretical and methodological approaches to development with an impressive array of analysis

- Whilst the book is about poverty what is more important is its concern about upward mobility but also the dynamics of this – it’s not just about how to get people out of poverty but how to keep them out of it. As Dr Kar notes upward mobility cannot just come from education and simple fixes. Upward mobility also requires the acquisition of certain attitudes and habitus – the poor do not lack in talent and intelligent but internalisation of exclusion becomes a perpetually self-fulfilling self-belief in terms of who can and can’t make it.

- The book argues for policy that is attuned to local traditions – to act with urgency whilst also taking the time to be considered thoughtful and reflective On gender, Dr Kar notes that there is attention to their lives but what are the issues concerning women’s employment? Given the broken ladder, Kar asks ‘how do we address the glass ceiling that women face?’

- Furthermore, Dr Kar is also concerned with how do to ensure equity across states, if as, Krishna proposes the government must recognise that one size does not fit all in terms of poverty alleviation and development.

Professor Maitreesh Ghatak

- Professor Maitreesh Ghatak acknowledges that ‘Mobility is the right metric to think about rather than static poverty’. Broken Ladder’s anecdotes makes it ‘humane’ – it considers ‘the landscape from which changes must be engineered’. He also warns that ‘We need to keep in mind the vector of empowerment and from a development perspective that should be given to the people’.

- On local governance, Professor Ghatak asks, ‘why is there political representation at the lower level but no administrative capacity?’ Ghatak asks How critical has local state capacity been in creating the scenario which you have described

- Krishna replies that ‘social mobility promoting organisations’ CSR, pure NGOs, etc that have taken it upon themselves to fill in the missing areas re career guidance, education, trips to workplaces etc.

- These examples need to be learned from and multiplied but not from a central design – they may be learned from and replicated in some areas but may not work in all.

- Professor Ghatak questions how much local issues can be fixed – for instance, teachers not showing and villagers being powerless to change this.

- There are also examples of villages where things work Krishna replies – it is about institutions over policies – eg to incentivise teachers, institutions must develop to promote such practices.

Audience discussion highlights

- (In response to Dr Ghatak) – PTAs (Parent Teacher Associations) are working in Rajasthan to boost school attendance on both sides – informal solutions may often work but you cannot easily scale them up as they might not achieve the same results.

- What are the characteristics of these institutions? What is well functioning? For instance, bearing in mind the above example, incentives could be given whereby teachers are given more salary for attendance and it is deducted twice for non-attendance.

- More study of successful institutions is required. Anthropologists and other social scientists based in India should study institutions to get a better idea of the human impact of their operations and what can be improved.

- The forms of development Krishna proposes must be part of an organic process – ‘we have lived with the problem for fifty years so if it takes another fifteen like the Chinese example – then I am willing to wait’ Krishna concludes, warning against governments which, in a bid to secure votes often implement ‘ham-fisted initiatives that do not work and often worsen situations’.

- There are however ‘pinpoints of light’ and these must be emulated, Professor Krishna concludes.

You can listen to a podcast of the workshop here.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Rebecca Bowers is blog editor at the LSE South Asia Centre and a final year PhD student in the Anthropology Department at the London School of Economics. Rebecca’s research explores the lives of female construction workers and their families in Bengaluru, India.

Rebecca Bowers is blog editor at the LSE South Asia Centre and a final year PhD student in the Anthropology Department at the London School of Economics. Rebecca’s research explores the lives of female construction workers and their families in Bengaluru, India.