India @ 70: LSE India Summit 2017 will feature panels discussing concerns relevant to India’s future while also exploring the key moments that have shaped the course of independent Indian history. Harish Alagappa looks back at the political and economic developments of the last 70 years.

India @ 70: LSE India Summit 2017 will feature panels discussing concerns relevant to India’s future while also exploring the key moments that have shaped the course of independent Indian history. Harish Alagappa looks back at the political and economic developments of the last 70 years.

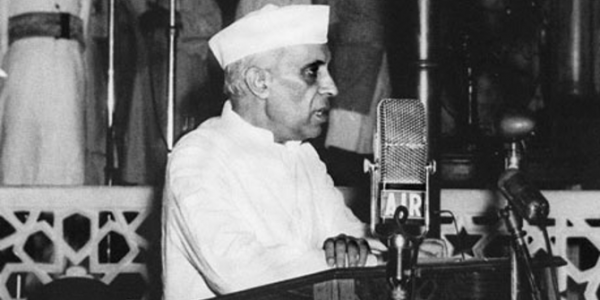

Urban legends purport that sometime in early August 1947 a group of astrologers met with Jawaharlal Nehru, urging the soon-to-be first Prime Minister of India to change the date of the handover of power. The signs, they claimed, were ominous and that August 15, 1947 was a terribly inauspicious day to begin any endeavour, particularly one that would involve the democratic self-rule of hundreds of millions newly-independent Indians. Nehru, a firm follower of the scientific tradition, decided to ignore their advice. But even those who did not subscribe to the idea of astrology were equally wary of what the future of independent India held, while others in Britain were scathing about the possibility of success. In an address to the House of Commons in March 1947, Winston Churchill, famous for his vociferous contempt for India and the Indian people (but not for the vast resources that Britain extracted from the subcontinent), announced that, ‘In handing over the Government of India to these so-called political classes, we are handing over to men of straw, of whom, in a few years, no trace will remain.’

Churchill was mistaken. Jawaharlal Nehru’s Congress Party won the first three general elections held in India in 1952, 1957, and 1962, remaining Prime Minister until his death in 1964. In power for 17 years, he remains India’s longest-serving Prime Minister to date.

His administration did have its flaws; his handling of the Kashmir infiltration in 1947-48 has been criticized, particularly his calling for a UN Security Council ceasefire just as the Indian Army was gaining the upper hand in the conflict. In addition, Nehru is often criticized for his decisions that led to – and mistakes made during – the Sino-Indian war of 1962, a conflict where India suffered twice as many casualties as China. Nevertheless, Nehru undertook a series of momentous initiatives whose benefits are being enjoyed by Indians to this day. His focus on ensuring India was home to high-calibre centres of higher education saw the establishment of the Institutes of National Importance under the Ministry of Human Resource Development, which led to the founding of some of India’s most prestigious universities, such as the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, and the Indian Institutes of Technology.

While India is technically a democracy – Indian elections for all their weaknesses are not easily subject to manipulations by the incumbent government – the Congress Party has enjoyed a near monopoly on power for most of independent Indian history. The Congress has been India’s ruling party, either on its own or as part of a coalition, for 58 of the last 70 years. This has contributed to two key problems in modern Indian politics: the feudalistic internal structure of political parties and dynastic politics. For example, members of the Nehru-Gandhi family have held the office of Prime Minister for 37 years between them. Despite an overwhelming national rejection of Jawaharlal Nehru’s great-grandson Rahul Gandhi during the 2014 general elections, he remains Vice-President and General Secretary of the Congress Party. Furthermore, dynasties are not uncommon at state and local level to this day.

Politics aside, India’s story over the last 70 years has been a curious and unpredictable one. Perhaps the best way to compartmentalise it is to divide into two eras, pre and post-liberalisation of the economy. Nehru sought to model the nation along the lines of Fabian Socialism, a philosophy to which he had become enamoured while at Trinity College, Cambridge and later at the Inns of Court School of Law (now part of City Law School) in London. His daughter, Indira Gandhi, sought to remodel that vision more along the lines of Soviet socialism, where the state controlled all. Thus, until the mid-80s, India remained a closed economy, distrustful of capitalist overtures from the West, clearly remembering that their erstwhile colonial masters had also first arrived in India as traders. However these policies brought the Indian economy to the brink of bankruptcy and in 1991 the liberalisation reforms were enacted, opening India up to the world.

Since then, India has taken a very different trajectory. Liberalisation fostered the creation of hitherto unheard of wealth for some, but the benefits of a globalised economy have not trickled down to the vast majority of India’s citizens. 40% of Indians currently live without functioning toilets or even a proper drainage system, and lack access to such basic neccessities as food, healthcare, clean water, electricity, and education. Thus, while there are 84 Indians on the Forbes Billionaire List (the 5th highest number of billionaires by country, behind the US, China, the UK, and Germany) almost 25% of Indians live below the poverty line in conditions only comparable to the poorest regions of sub-Saharan Africa.

But India is still better off today than it has been at any point in the last 70 years, or in the two centuries of British rule before that. More Indians are literate than ever before, hundreds of millions have access to modern communications networks, and opportunities for personal economic growth are abundant. After decades of living in the shadow of colonialism, Indians from major urban centres such as Mumbai, Delhi, and Bangalore are reconciling modern education and ideals with their cultural and linguistic roots.

Clichés abound of the Indian economy morphing from a slow, lumbering elephant to a dynamic and aggressive tiger. Today India is a regional power aspiring to superpower status. The greatest change witnessed, perhaps, has been one of mind-set. Indian millennials, born in a vibrant economy, exposed to global culture, and imbued with a sense of optimism and manifest destiny at odds with the traditionalism and prudence of their parents, went out with the intention of conquering the world. The ethos of modern India is in many ways similar to the United States of the 1950s, with its economic liberalism, expectant patriotism, and social conservatism on the surface, with the rumblings of a major revolution around the corner. The 70th anniversary therefore a pivotal moment in the ‘tryst with destiny’ that Nehru famously spoke of as the clock struck midnight on 15 August 1947, and it’s likely that the decades to come are going to be as unpredictable and fascinating as the preceding ones.

India @ 70: LSE India Summit, presented by Apollo Tyres Ltd, takes place at the Habitat Centre in Delhi on 29-31 March 2017. Click here for more information about the conference, including a full conference schedule.

Tickets are now sold out but there will be a livestream of the panels. Click here to sign up.

About the Author

Harish Alagappa is a writer signed with the Asia Literary Agency and is currently working on his first book. He was formerly an Assistant Editor with the New Delhi-based think tank, TERI (The Energy and Resources Institute), and has written for The Times of India, The Encyclopedia of Energy, The Score Magazine, and Sportskeeda. In his spare time, he’s an amateur stand-up comic, quiz enthusiast, and Radiohead aficionado. He tweets @chaosverse.

Harish Alagappa is a writer signed with the Asia Literary Agency and is currently working on his first book. He was formerly an Assistant Editor with the New Delhi-based think tank, TERI (The Energy and Resources Institute), and has written for The Times of India, The Encyclopedia of Energy, The Score Magazine, and Sportskeeda. In his spare time, he’s an amateur stand-up comic, quiz enthusiast, and Radiohead aficionado. He tweets @chaosverse.

Wow! its an awesome article.

We are proud of you Harish.In this era of doctors and engineers I was really happy to know that you are into something different and into creative stuff.

You are into varied fields….from writing to quizzing to stand up comedy…..you are indeed versatile…Three cheers to you…!!!!!!

Sulekha Mohan

DGM(Retd)

Canara Bank