In February Ali Rez and Assam Khalid spoke at the South Asia Centre on the topic of art and marketing as a protest device in Pakistan. Before the event they were in conversation with Hasna Syed and Sonali Campion about their social impact projects, advertising in Pakistan and the need for brands to be authentic in their communications.

HS: How did Not A Bug Splat, which featured a gigantic portrait of a girl laid out in North West Pakistan to protest against drone warfare, come about?

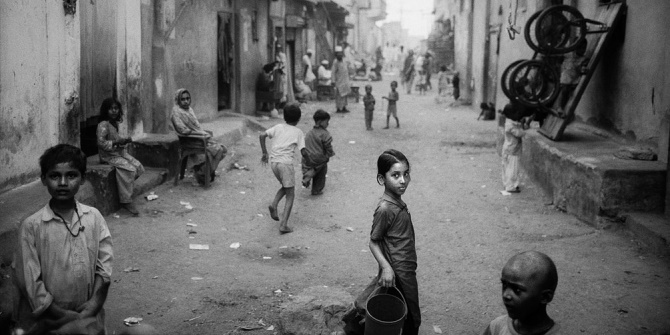

AR: The issue of collateral damage brought about by drone strikes was there in Pakistan for quite a while. We had been doing a project with JR, who’s the artist that started The Inside Out movement. We did a portrait series of minority members in the communities of Karachi and Lahore, entitled The Minorities. Later we heard about an NGO that was working to take the cases of people who were affected by drone strikes to the courts, so we decided to help them using the idea which had come from working with JR. Everything just sort of fit together.

SC: Was the portrait from the initial project or was that shot specially?

AR: No, the portrait actually has a really good story behind it. The photograph that we used was shot by photographer Noor Behram who had specialised in travelling quickly to sites that were bombed to collect photographic evidence. He came across these three children who had just lost their parents, their siblings, and their home in a strike. They were in shock. They had no idea what had happened. We picked the picture because that girl was an actual victim of drone strikes. We tried to find her but last we heard she was taken to a camp in Afghanistan and then we lost the trace unfortunately.

HS: This project espoused a lot of dialogue and awareness on the issue of drone strikes (the project received over 3.5 billion impressions globally and $182 million in earned media). Has action been taken as a result?

AR: The problem was in order to bring about a change in policy, in both domestic and international, you had to bring that international pressure. There were lots of protests happening in Pakistan. None of them were getting the traction we needed. This project took it to that level, every major news agency covered it. We had turned the tables on who was watching whom. The pressure that was generated did change things in Pakistan. It brought about some legal changes, some government policy changes and the programme has almost died out now.

HS: In the No Man’s Land project you organised a game of cricket between Indian and Pakistani kids on the Wagah Border. Did the children have any idea about the issues present on this topic?

AR: This was part of a project we were doing for Citizens Archive of Pakistan. They had a programme called Exchange for Change, where they took 20 Pakistani schoolchildren to India and vice versa – so they could experience each other’s countries on ground-level. Before that, there was an entire year of correspondence between the children and schools. Letters, postcards, artworks, things that said ‘life in Pakistan is like this, and life in India is like this’ and of course there were lots of similarities. What we wanted to do was to generate some news around the programme itself, and we knew that this would require some sort of activation. Just telling people about the project is not enough of a talking point. We planned the match, and sort of did it without permission. We just got there and told the border guards said ‘can we do this?’ At first they were hesitant but eventually they agreed. The funny thing is we did this crossing over into India. It got into the news so when we were crossing back a week later I actually brought a paper with me to show the border guards, which went down well.

SC: How do you select these projects? Do people come to you or do you have particular interests you want to pursue?

AR: Both. If you come to our office, we’ve got a wall where we put up papers of things we would like to work on. But in other cases an issue is brought to us. One project you’ll see today is for UN Women, and its for Women’s rights. UN Women had been talking to us for a while. We’d gone to them last year with a project to challenge child marriage in Pakistan. That built a relationship and then they came back and said ‘can we do something about the issue of domestic violence?’ We had an idea and took it back to them. That has developed into a pretty cool campaign which is doing well.

AK: Some of them come to us with a brief, for example WWF approached us if we can do something for the environment. Other times it’s just BBDO, there is a culture where you can work on causes close to your heart and the organisation will support you. But it can take time. Bug Splat, for example, took around a year and a half to materialise. We came across a lot of ‘no you can’t do this, no you can’t do that’. It took us a while to find the right people to say ‘yes, let’s do this’.

AR: And ultimately we still had to do it without permission. It was just one of those things, the more people you ask, the more they were afraid of doing it.

HS: How do you convince people to get involved? Especially with contentious issues?

AR: It’s interesting because this question comes up often. We think that for the number of people that don’t want to have anything to do with a certain issue, there are an equal number of people that are actually affected to the extent that they do want to help.

We did a project for an organisation that helps women who are victims of acid attacks. Even in that case, we put the word out that we’re going to be doing this campaign and we want women to come forward. This was a situation where they had been hurt very badly, you would imagine that they would be living under so much fear, but we had scores of women who were affected and wanted to talk about it.

HS: A lot of companies these days are jumping onto the bandwagon and using social justice in their advertisements. What are your thoughts on that about the efficacy of this?

AR: This trend is more visible on the Western side, than it is in Pakistan. Brands in Pakistan are starting to approach social issues, although they steer clear of the most polarising ones. We did a project with a client of ours who made mattresses. They asked for an outdoor campaign, and we built outdoor boards that converted into beds for homeless people with the mattress on them. We had to convince them to do for a while but eventually they embraced it because they recognised it was for a good social cause. That was the limit though. I don’t think they’re necessarily willing to question more serious things.

We’ve noticed India is further ahead on this. Ariel (detergent) has taken a stance on gender equality, questioning why washing clothes is a woman’s job. But in Pakistan people aren’t yet willing to question government, the army, or religion

SC: What do you see as the mechanism for advertising to bring social change? When you come up with a campaign, in an ideal world, how would that piece of ‘goodvertising’ be converted into an outcome?

AK: The strategy differs depending on the desired outcome. For the UN Women campaign we needed the campaign to be picked globally because that will put pressure on our government. If we were just to have local media pick up this campaign, nothing would happen. That change happened when there’s pressure from outside sources that the world is noticing.

But at the same time the international campaign was just one leg of it. We also need to change behaviours. Our big media campaign – which was in English – wouldn’t do that. So we created a leg of that campaign which went on ground, and actually engaged with the masses and changed mindsets.

AR: We’ve also seen our campaigns influencing others. Every summer you are just inundated with ads from textile producers showing women as objects. But for the first time I’ve seen Gul Ahmed, which is one of the textile largest companies, depicting women as powerful. People are posting now, ‘is this inspired by the UN Women campaign?’ That’s the question people are asking because they’ve seen our work and they can see parallels.

Once one company takes a different stance it shifts the balance of the argument because their competitors have to change their thinking. After we did Bug Splat, there was another campaign where they printed missing children’s faces on kites. Kids use the kites, they fall somewhere, somebody else picks it up, there’s a number on it – have you seen this child? It’s actually worked because they’ve found people, but it’s a really creative device to use. They’ve gone out of the sphere of ‘let’s just print a poster’ and it’s nice to see those knock-on outcomes.

SC: Is there a danger of cynicism from audiences, if the brands are saying ‘look we’re putting on a positive campaign’ while at the same time behaving badly in other ways?

AK: Absolutely, so social media is a dangerous playing field, because it takes one second for your audience members to turn on you. We saw this happen with the clothing brand DYOT, short for Do Your Own Thing. It was supposed to be a clothing brand about empowering women but they just went about it the wrong way and audiences ripped them apart. Consumers also know what’s real, and what’s been done with the right intent.

AR: It’s what we refer to as the bulls**t meter. Even when we did Bug Splat there was a lot of criticism and cynicism. People questioned if it was actually real – they said it’s photoshopped. But then you let the work answer, it’s like Wikipedia, people will collectively come to the right conclusion. That is something we also advise brands, whether they be NGOs or commercial, they need to be careful about honesty.

If your intent is to do something good in order to sell more product then we always tell brands there is nothing wrong with that, don’t try and hide it just make sure you are actually doing something good for somebody. A good example was when Samsung was selling large screen TVs in Argentina. At that time there were a lot of deaths happening on single lane highways when people were trying to overtake large trucks and couldn’t see oncoming traffic. As part of their marketing, Samsung put large screens on the back of the truck and a camera on the front so cars behind could see ahead of the truck. It’s a simple device but it’s an innovative way to sell a TV. You’re not talking about the colours and beauty, instead they did something good that saved lives. The traffic police now in Argentina started talking about adopting it as a measure to install on all trucks.

Pakistan @ 70: LSE Pakistan Summit takes place in the Institute of Business Administration City Campus, Karachi on 10-11 April 2017. It will feature a panel on Art and Modernity, featuring Ali Rez alongside Ali Nobil Ahmad, Farida Batool, Fasi Zaka and Iftikhar Dadi. The Summit is free but registration is required – secure your space here before 8 April. Click here for the programme and speaker bios.

About the Authors

Ali Rez is a creative director with more than 16 years of experience: he has won in excess of 100 major advertising awards, and in 2016 is ranked amongst the top 10 creatives in the world by the Big Won report.

Ali Rez is a creative director with more than 16 years of experience: he has won in excess of 100 major advertising awards, and in 2016 is ranked amongst the top 10 creatives in the world by the Big Won report.

Assam Khalid has a Masters in Advertising from the University of Texas at Austin and over a decade of experience in creative communication. His passion for creating disruptive ideas has won him more than 75 international industry accolades in the last two years alone.

Assam Khalid has a Masters in Advertising from the University of Texas at Austin and over a decade of experience in creative communication. His passion for creating disruptive ideas has won him more than 75 international industry accolades in the last two years alone.

Hasna Syed is a Master’s student at the London School of Economics & Political Science. She is also a youth advocate and activist. Her initiatives have been featured in various media outlets including the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) and Global News. Hasna’s song, Raise Our Voices, co-written with her siblings is currently featured on United Nations’ websites as part of the ILO’s Music Against Child Labour Campaign. Hasna co-founded Global Youth Impact (Facebook: GYI – Global Youth Impact), an NGO that gives youth a platform to be change-makers locally and globally.

Hasna Syed is a Master’s student at the London School of Economics & Political Science. She is also a youth advocate and activist. Her initiatives have been featured in various media outlets including the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) and Global News. Hasna’s song, Raise Our Voices, co-written with her siblings is currently featured on United Nations’ websites as part of the ILO’s Music Against Child Labour Campaign. Hasna co-founded Global Youth Impact (Facebook: GYI – Global Youth Impact), an NGO that gives youth a platform to be change-makers locally and globally.

Sonali Campion is Communications and Events Officer at the South Asia Centre. She holds a BA (Hons) in History from the University of Oxford and an MSc in Comparative Politics from LSE. She tweets @sonalijcampion.

Sonali Campion is Communications and Events Officer at the South Asia Centre. She holds a BA (Hons) in History from the University of Oxford and an MSc in Comparative Politics from LSE. She tweets @sonalijcampion.