In Populism and Power: Farmers’ Movement in Western India, D. N. Dhanagare comprehensively traces the farmers’ movement in Maharashtra over three decades. Khurshed Alam finds the book addresses a wide range of fundamental issues relating to populism and peasant mobilization in India, and writes that it is an excellent resource for students and researchers interested in sociology, gender and social movements.

Populism and Power: Farmers’ Movement in Western India, 1980-2014. D. N. Dhanagare. Routledge India 2015.

The final work by prominent Indian sociologist D. N. Dhanagare, who passed away earlier this year, covers the strategic and structural aspects of peasants’ movements in India. It explores in detail the rise and fall of the peasants’ movements in Maharashtra between 1980 and 2014, taking on a variety of fundamental issues like populist movements and their relevance to India; the conditions that enable Indian farmers to mobilise; the relationships between leaders and followers/activists, and between movements and class interests; and the nature of class hegemony. In addition, the book looks at the failure of populism to get electoral support, or of succeeding in the cases it does get power.

The final work by prominent Indian sociologist D. N. Dhanagare, who passed away earlier this year, covers the strategic and structural aspects of peasants’ movements in India. It explores in detail the rise and fall of the peasants’ movements in Maharashtra between 1980 and 2014, taking on a variety of fundamental issues like populist movements and their relevance to India; the conditions that enable Indian farmers to mobilise; the relationships between leaders and followers/activists, and between movements and class interests; and the nature of class hegemony. In addition, the book looks at the failure of populism to get electoral support, or of succeeding in the cases it does get power.

Theory and context

The first chapter of the book offers an excellent theoretical review which covers both western and Indian perspectives and develops a framework of analysis for the movements under study. It also explores major theoretical perspectives critically, covering resource mobilisation, Marxism, the subaltern approach, new social movements, and finally examining possibilities of theoretical populism. Although Marxist perspectives dominate this overview of populist movements, and one might not agree with author on every point, this section gives a rich critical understanding of the theory, enabling the reader to develop their own viewpoint.

The second chapter covers the farmers’ movement in Maharashtra, drawing on both fieldwork and secondary sources. In his analysis, the author also touches upon other contemporary on-going peasant movements of other parts of India and their ideological or strategic similarities and dissimilarities. He also outlines some of the historical context, building on his earlier book, Peasant Movements in India 1920 to 1950 (New Delhi, OUP, 1983).

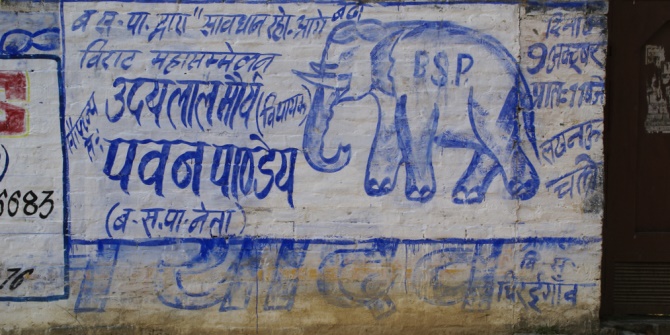

In this chapter, Dhanagare introduces Shetkari Sanghatana, a leading farmers’ organisation which led the peasant movement in Maharashtra during the period under analysis. They tackled issues from declining profitability and terms of trade, to the particular concerns of specific constituencies, such as onion growers, sugarcane cultivators and cotton growers. Their agitations reflected the main demands common to all contemporary farmers’ movements, namely for cost-based prices for all marketable surplus, subsidised inputs, concessions in credit, loans and taxes, a reduction in electricity and water charges, and so on.

Class and politics

The third chapter covers the class character of peasants’ movement in Maharashtra, 1980-2011. Dhanagare critically examines the emergence of rich farmers as a class, and questions whether economic populism or class is the key driver. The author narrates how the movement evolved from predominantly peasant agitation to a mobilisation with wider appeal because the campaigns served the interests of all classes, for example for remunerative prices of farm produce. This transition resulted in left leaning critics of those movements (who were initially supportive), who argued that the rich farmers and the better off peasants would reap the majority of the benefits because they have more marketable surpluses. However, the author presents evidence to contend that small and middle farmers were able to increase their income selling surpluses, particularly as many transitioned to producing more cash crops over the three decades.

Dhanagare also explores the link between the farmers’ movements and politics. For example, he discusses how a rich farmer’s class emerged in independent India due to the rural development strategy adopted, so even after four decades of land reforms the pattern of landholding shows a highly skewed distribution. As a result, landed power continues to be a major factor in Indian politics and society, although it is noted that rich landowning groups tended to prefer passive resistance as a means of collective protest as they feared militancy may result in them to losing their surplus land. At the other end of the spectrum, the Shetkari Sanghatana has taken both anti-establishment and pro-establishment stands as the occasion demanded through electoral contests. Debates around the role of middle peasant in the Maharashtra movement and controlling state politics are also explored. However, the book is missing an assessment of the relational and distribution impacts of the movements discussed.

Women’s activism

The fifth chapter looks at participation of women, who were voluntarily involved from the first agitation in 1980. It explores the social background of female activists and women’s mobilisation in other states, and theorises women’s oppression. It traces how the sustained participation of women in different movements led to the Shetkari Sanghatana establishing a separate women’s branch of the organisation with a distinct agenda.The chapter contains accounts of women being arrested for their participation in protests, and travelling to Delhi and even further a field to participate in seminars, workshops, conferences and national farmers’ rallies. The women campaigned successfully for village liquor shops to be closed, and as a result of the Laxmi Mukti mobilisation for women’s rights to property about two lakh (200,000) had a portion of their family’s land transferred into their names (albeit at their husband’s discretion). They also got elected in local government bodies, and put pressure on the state government which then granted 30 per cent reserved seats for women in Panchayat elections.

However, despite these successes and the hope inspired among rural women, this branch of the movement in Maharashtra was a disappointment in the long run. Dhanagare presents evidence to indicate that the leader of the Shetkari Sanghatana was critical of feminism, and mobilising women on a mass scale was a tokenistic gesture to serve the symbolic purpose. The gains in terms of gender equality and justice were limited and even the breakthroughs came with challenges. For example, even though many women had land titles transferred into their names, they couldn’t always navigate the systems required to manage the land, such as accessing loans, seeds and fertilizers or dealing with judicial courts in cases where the land was under litigation. This was either because of the convoluted nature of the unfamiliar systems, or because they were barred by social norms.

Conclusion

Other chapters explore the farmers’ movement response to new economic reforms, the electoral politics of farmers’ movement and how it damaged the peasant movement in Maharashtra, and the decline of the farmers’ movement as a result of the structural changes that have taken place in Indian economy. A strange feature of the book is that it adopts the neo-Marxist analytical approach without fully subscribing the associated ideas. This raises the question of whether it should adopt a more functionalist view on the issue or at least blend the two. The book could also have been made more reader friendly by the inclusion of a short introduction offering a summary of all the chapters.

However, Populism and Power is an excellent resource for students and researchers interested in sociology, gender and social movements, and will undoubtedly remain relevant for years to come. The title almost undersells the book by suggesting it is entirely focused on Western India, even though it frequently explores the wider context and would be of interest to readers interested in the national picture. The analysis would also be extremely valuable for policymakers looking to addressing the needs of the farmers across the country.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Dr Khurshed Alam is the Chairman of BISR Trust. He worked as a senior consultant in various government departments, and at the World Bank, JICA, ADB and USAID. He was involved in preparing the national plan for the country by the government of Bangladesh in 2008. He was also a university teacher. He has published 35+ research articles in international journals. Email: khurshedbisr@gmail.com and web: www.drkhurshedalam.info.