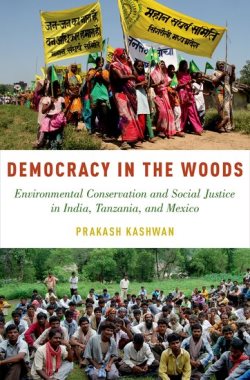

In Democracy in the Woods: Environmental Conservation and Social Justice in India, Tanzania and Mexico, Prakash Kashwan contributes to urgent debates surrounding forest and land rights by looking at how competing agendas of environmental protection and social justice have been balanced in three country-specific case studies drawn from India, Tanzania and Mexico. This is a powerful portrayal of the complexities of governance and the pursuit of justice when it comes to land displacement and environmental conservation, writes Indrani Sigamany.

Democracy in the Woods: Environmental Conservation and Social Justice in India, Tanzania and Mexico. Prakash Kashwan. Oxford University Press. 2017.

In an era of free market globalisation, in which environmental conservation and extractive industries take priority over indigenous claims to ancestral lands, Prakash Kashwan’s Democracy in the Woods: Environmental Conservation and Social Justice in India, Tanzania and Mexico is an opportune and timely book for scholars studying the social justice aspects of nature conservation within democratic contexts. It offers a valuable contribution to debates around forest regions occurring on every continent, which range from dispossession of indigenous peoples’ lands to tensions between conservation and economic development. Following Kashwan’s firm belief that environmental conservation and social justice are the two most important issues of our times, the book gives prominence to the inclusion of social justice within narratives of nature conservation and positions human rights within a political morality that is often missing in these discussions.

In an era of free market globalisation, in which environmental conservation and extractive industries take priority over indigenous claims to ancestral lands, Prakash Kashwan’s Democracy in the Woods: Environmental Conservation and Social Justice in India, Tanzania and Mexico is an opportune and timely book for scholars studying the social justice aspects of nature conservation within democratic contexts. It offers a valuable contribution to debates around forest regions occurring on every continent, which range from dispossession of indigenous peoples’ lands to tensions between conservation and economic development. Following Kashwan’s firm belief that environmental conservation and social justice are the two most important issues of our times, the book gives prominence to the inclusion of social justice within narratives of nature conservation and positions human rights within a political morality that is often missing in these discussions.

Kashwan uses social justice as a lens through which to examine environmental and conservation policies in the context of land rights claims by indigenous forest peoples. Kashwan analyses the political institutions and policy processes that shaped environmental policies and land reforms during the 1990s and 2000s in India, Tanzania and Mexico. Using country-specific comparisons of tensions between political elites and peasant mobilisations over land rights, the book examines the resulting dichotomies between social justice and environmental conservation. It focuses on the politically mediated interactions between states and citizens, which have led to different forms of ‘transformational institutional change’ (117) in the three contexts. This comparative multi-country analysis is a key strength of the book.

Kashwan’s three country-specific case studies also trace the historical trajectories of unfolding forest rights, and the socio-political landscapes underpinning transformational institutional changes. The case studies are therefore grounded in discussions of history, the politics of institutional change, public accountability and policymaking, which culminate in different realisations of social justice within nature conservation. The author outlines the political evolution of forest governance under colonial rule and post-independence as well as in contemporary periods, as a methodology for ‘separating out the effects of path dependence from contemporary institutional structures that shape policy making’ (213).

Democracy in the Woods maps the extent to which state-controlled forests and the colonial extractive exploitation of forest resources continue in contemporary forest policies in each context. India and Tanzania, where forests are state-controlled, offer a useful comparison to Mexico. The Mexican government’s large-scale land redistribution was implemented to counter the power of political elites after the revolution, which ensured an unprecedented control of forest lands for Mexican forest communities. This, Kashwan argues, has resulted in an alignment of community forestry with conservation programmes in Mexico, in stark contrast to conservation policies in India and Tanzania that have excluded forest communities.

The case studies also illuminate the centrality of political engagement in shaping historical and contemporary policies, and outline relations between peasant communities and political elites in the three countries. Tanzanian forest peoples are shown to have the least political clout, and ‘the task of steering it in the right direction is hampered by Tanzanian leaders’ single-minded focus on the goals of economic growth without ensuring that a majority of the country’s population acutally benefits from such economic growth’ (203). In India, forest communities have been a stronger mobilising force, and have also benefitted from a secure multi-party system. Mexico is shown to be the greatest success story, with the strength of peasant mobilisation coupled with ‘inter-elite competition’ fuelling a partnership with the government that has benefitted indigenous and peasant welfare. This, Kashwan contends, also has had lasting and positive implications for climate change policies. For example, the failure of the Kyoto Protocol, which the author refers to as the ‘strongest international environmental governance agreement ever’ (211), is attributed by Kashwan to it not having taken domestic politics sufficiently into account. All three case studies nonetheless represent the conflict between redistributive policies and environmental protection.

A third strand of analysis illuminated by the case studies is how the international community influences domestic forest governmentality and vice versa. Kashwan concludes that ‘domestic policies in developing countries also greatly influence the outcomes of international conservation’. An example cited are the ‘perverse incentives for state agencies to promote unsustainable and wasteful environmental policies and programs’, which normal domestic policies might constrain, but which could be created by global environmental governance (211). This significant analysis goes beyond the conventional perspective of the influence of international conventions on domestic policies. Instead, Kashwan argues that:

while the international environmental community has to engage with domestic political actors, such engagements should be broad-based engagements with a plurality of actors and voices, with the goal of fostering public demands for global environmental quality (211).

The rich conclusions of the book are deliberately not based on a particular theory, but instead use the ‘political economy of institutions framework, comprised of conceptual tools drawn from historical institutionalism, institutional analysis, development studies and comparative politics’. Kashwan posits that eclectic frameworks such as this are more conducive to understanding institutional change in relation to environmental conservation and social justice, because of the ‘inherent diversity and complexity of the process’. Kashwan’s empirical study also uses a wide range of data on the displacement of indigenous peoples from their lands based on extensive fieldwork. The book would nonetheless have benefitted from a better disaggregated and representative analysis of the inequalities which exist within indigenous communities themselves as well as the effects of land dispossession or successful land claims on these. Kashwan’s argument that institutions ‘reflect the intricate layers of social economic and political inequalities within a society’ could particularly have been deepened by exploring gender inequalities and comparing and contrasting social dynamics within the three forest communities (207).

Despite this, the book is thoroughly documented and comprehensively cited. The analysis is nuanced and contributes original findings, which challenge the conventional understanding of the conflict between the environment and economic development. Kashwan posits that these might actually reinforce each other, as demonstrated by the argument that land conflicts and poverty alleviation need addressing in order to respond to the root causes of deforestation. Finally, he highlights the position of forest land rights between social justice and environmental conservation, arguing that they cannot be separated from forest policy reforms and sustainable development.

Democracy in the Woods is a powerful portrayal of the complexities of governance and justice contained in the issues of land displacement and environmental conservation, which can both contribute to widening livelihood and habitat insecurity. The trespassing on human rights creates an urgency to the debates explored in this book. Institutions reflect the dynamics in a society, and Kashwan argues that unequal access to natural resources, social justice and environmental power presents ‘a set of interconnected social dilemmas of the grandest scale’, here embodied in forest rights and the rationale for forest protection.

This post originally appeared on LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Indrani Sigamany has worked on social justice and poverty alleviation for more than 25 years. Specialising in civil society strengthening, gender and human rights, Indrani has straddling roles as both a practitioner and an academic, and has worked in more than fifteen countries in the field of international development. Indrani’s PhD, from the Centre for Applied Human Rights, York Law School, University of York, UK, focuses on mobile indigenous peoples, land displacement and forest rights legislation. Her Masters degrees are from the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS), Erasmus University, Rotterdam; and from Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai. She has a Bachelor’s degree from Whitman College, WA, USA. Indrani lives in Oxford, England.