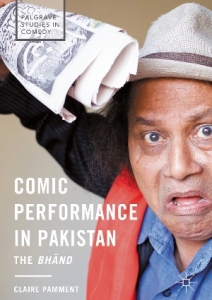

In Comic Performance in Pakistan: The Bhānd, Claire Pamment explores the centuries old tradition of Pakistani bhand performances which have used comedy to tread a line between flattery and challenging patron’s authority. Asad Abbasi, however argues that Pamment’s work is anything but comedy and reveals the discriminations faced by this subaltern population.

The Punjabi stage show weaves together abrasive and acerbic wit, and hyper-sexualized dance sequences with nationalistic, moral and religious dialogues. In these stage shows, nothing is sacred, yet everything is sacrosanct. This contradictory art form, with its simultaneous ‘asserting and debunking’, as Claire Pamment demonstrates in Comic Performance in Pakistan (2017), has existed in South Asia for centuries.

‘In Punjab, bhands comprise a comic male duo’. One, the ‘straight man’, is a serious, authoritarian figure. The other, ‘a chaotic and more radical clown’ (2017:6). The Punjabi popular stage theatre is but one incarnation of the ‘bhand’ phenomenon. For centuries, by using this basic structure to cover every topic from the ‘donkey cart to the aeroplane’, bhands have performed for kings, rulers, landlords, politicians, peasants, working class and passersby.

The bhands’ genealogy, according to Pamment, draws from the Brahmin jesters— like Tenali Rama and Raja Birbal— and the Sufi wise fools— like Bahlul and Mullah Nasruddin. Whereas the Sufi wise fools performed for the royals and the commons, Brahmin jesters performed exclusively for the royal court. Yet, both— the Brahmin jester and the sufi fool— impart moral edict to their audience. The bhand, however, is beyond moral edicts and emerges as a complex, critical, and even controversial, figure.

The bhand is a cynic, a critic, a Sufi, a saint, a satan, a wise man, a fool. The bhand spares nobody. The bhand questions your conservative attitude and your liberalism. The bhand banishes you for wearing a tie or fashioning a beard. The bhand mocks you for wearing jeans or a veil. The bhand heckles you when you look at a woman or you shy away from looking. The bhand mocks you for your clothes or lack thereof. The bhand does not care about your religion nor your sect. The bhand does not care about your gender, nor your orientation. Everything that you pretend to be, is likely to be questioned, ridiculed, satirized. Depending on the day of the week and the mood of the bhand, you will all be ridiculed, some more than others.

The bhand is a cynic, a critic, a Sufi, a saint, a satan, a wise man, a fool. The bhand spares nobody. The bhand questions your conservative attitude and your liberalism. The bhand banishes you for wearing a tie or fashioning a beard. The bhand mocks you for wearing jeans or a veil. The bhand heckles you when you look at a woman or you shy away from looking. The bhand mocks you for your clothes or lack thereof. The bhand does not care about your religion nor your sect. The bhand does not care about your gender, nor your orientation. Everything that you pretend to be, is likely to be questioned, ridiculed, satirized. Depending on the day of the week and the mood of the bhand, you will all be ridiculed, some more than others.

But simultaneously, your cultural status and social standing is praised. Your good deeds are publicly announced and emphasized by the bhand. If you are rich, or from a wealthy family, you will be praised for your wealth and ‘good’ family. If you lack wealth, you will be praised for you modesty. You are thanked for your patronage and high status, intelligence, beauty, luck and generosity. Praise bestowed, order restored.

This is the package that you pay for, this is the package that the bhand has specialised in for centuries. This, Claire Pamment argues, is the process of ‘asserting’ and debunking’ and this is the bhand’s livelihood.

To suggest that Pamment’s book explores only the bhands in Punjab would be to say that Ginzberg’s Cheese and Worms only traces daily struggles of a sixteenth century Italian miller. Prima facie, Ginzburg focuses on an individual in the sixteenth century, yet his subject matter is broader, even dangerous, as it discusses enlightenment, religion, education, culture and so forth. Similarly, Pamment focuses on the art of bhand but in doing so she covers caste ideology in Pakistan; the prominence of class hierarchies; the art of dissent; the role of women in an all-male industry; and the perseverance, struggles and survival of bhands. Pamment, unfortunately, does so without Ginzberg’s style and storytelling. Ginzberg transports you to Menocchio’s trial, but Pamment intermittently jolts her readers with academic vernacular, which results in an intellectual irritant. The language, concepts and themes of the book suggests that Pamment only targets academics. It is unfortunate because Pamment’s work deserves wider— much wider— audience.

Pamment classifies bhands into three categories: the wedding bhands, the stage show bhands and the television bhands. Each classification differs from the other two with regards to the audience, medium of performance, freedom of expression, control over the script material, and, most importantly, income. The television bhands earn the highest income, whereas the wedding bhands face incessant penury. Theatre bhands enjoy varying fame, varying income but hold the most freedom to express agency, barring any state sanctions, whilst the wedding bhands are expert genealogists and ‘can disclose embarrassing information that patrons would rather keep hidden, and, conversely announce histories that patrons would like to project’ (110).

Many bhands proudly claim to have performed for the Bhutto family and the Sharif family. If the bhand exposes class hierarchies, why would politicians invite them? The reason is simple. Through praise the bhand elevates, and through criticism the bhand humanizes the patron among the wedding attendees.

The Bhand disturbs and affirms the class hierarchies through debunking and asserting. For such qualities, politicians feel compelled to invite and financially support the bhands.

When the bhand performs in front of the working class or rural family, the bhand talks about ‘aspirations of making it rich in the city……[but] also criticizes the symbols of power of the ruling elite establishment’ (128). The bhand tweaks the performance to suit the specific audience. This requires excellent and extensive research. Pamment recalls that when she met one of the bhands for an interview, he was well informed about Pamment and her family.

The bhands are not fans of two groups: The aspiring middle class and the Army. The reason is that both these groups, the middle class and the Army, continuously try to distance itself from the bhands.

The aspiring middle-class continues to distance itself from the bhand and the bhand culture. Classical, semi-classical music and bagpipes are the wedding entertainments at the commercial wedding halls. In such a setting, ‘the bhand potentially becomes a difficult encounter for those with things to hide, the bourgeoisie’s nightmare reminding audiences from where they apparently come and critiquing their ambition of power’ (123). The reason the bhands dislike the army is far simpler: Army barracks are ‘a comedy no-go zones’ (119-120).

The entrance to the old Aziz theatre in Taxali gate, Lahore. Image source: Walled City of Lahore Authority, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Ironically, the Army is responsible for the bhands movement into theatre and television. Post 1947, with Pakistan a sovereign country, the Lahore theatre culture, Pamment notes, relied on Anglo-Saxon plays adopted in Urdu for the upper-middle class milieu and sanitized from any political critique. Until 1970s, the theatre ‘was a place of the elite by the elites and for the elites’ (136). The elites banished and criticized those from the bhand background for having ‘no literary background’. The deputy director ‘felt… [the bhand]… should be kept separate from the theatre’ (141). Forget the discrimination against other ethnicities, Pamment shows how caste and class segregates people who speak the same language, belong to the same region and associate to the same religion.

With General Zia’s cultural banishments, many theatre actors moved into television. The bhands took over the empty theatre. By the time Benazir Bhutto came to power, the bhands had gained financial support to run the popular stage theatre. By 1990s, the burlesque, sexualized dance performance entered the popular Punjabi stage theatres. Few dancers even headlined the shows and commanded higher fees.

In this context, Pamment focuses on the issue of the ‘male gaze’. Pamment argues that for the female characters, dancing provides a route to enter popular stage shows. Otherwise, the all-male industry assigned women ephemeral appearance, without role, without agency. The dancer ‘by playing with the conventions of theatre and its gazing patterns, she [the female performer] knowingly uses objectification to turn the gaze back on the patriarchal structure and in doing so she asserts power’ (146). Pamment understands that she is taking a difficult position and acknowledges the ‘criticism from feminist quarters that these women were reduced to “consumerist objects” and controlled by male producers and audiences’ (144-145). Pamment understands that stage show dancers are objectified, but she argues that, just like the bhands, the dancers use their precarious status, to counter the male gaze.

It is not just the ‘feminist quarters’ or people from the parallel theatre but ‘many of the popular theatre’s formative actors are keen to disassociate themselves from its contemporary sexual context and have left the stage or have passed away in disillusionment’ (165).

Once again, Army plays an indirect role in the bhand’s movement from theatre to television. It was General Musharraf’s appearance on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart that inspired Aftab Iqbal, an influential journalist, to create Hasb-e-Haal (177). In Hasb-e-Haal, Iqbal plays a serious ‘anchor’ and Sohail Ahmed, the bhand, plays a fool. But soon, Pamment writes, the off-screen rifts between the two emerged as both men fought to control the narrative of the show. In an interview, Iqbal tells Pamment that Ahmed is ‘just a performer’ who fancies himself as a political pundit (179). In this case, Ahmed had the last laugh as Iqbal left the show to start a new show where he plays the same, serious, wise man ‘commanding’ eight bhands who perform and entertain the audience. Hasb-e-haal, based on the bhand format, started a new trend which dozens of networks now copy.

In each setting, the bhands are assigned a low-status by the society. The bhand, however, fights this status with praise and with critique. On wedding ceremonies, on stage, or on tele, the bhands continue to fight the hierarchies which disapproves them and praise the hierarchies which supports them. In each setting, Pamment sides with the bhands and their struggles against the social and cultural stigma attached to the art. Perhaps, Pamment sides with the bhands bit too much.

For example, the popular stage show begins with the national anthem followed immediately with a song layered with sexual undertones. This contrast, Pamment feels, is ‘playful manipulation of hierarchical structures.’ (134). Yet, a simpler explanation is that the bhands fulfils the audience expectation: a bit of patriotism mixed with a bit of perversity. Similarly, Pamment subscribes too much power into bhand’s critique of the political class. The structure of the bhand performance, the debunking and asserting, is based on the political economy of the the bhand. The bhand relies on the patron’s generous gift. Could the bhand bite the hand that feeds it? Within this structure, very few bhands criticise politicians vehemently, but many others do it with caution.

Pamment briefly explores yet another important topic: the right of representation. The bhands argue that the cultural elites of Lahore (and Karachi), with their ‘first-class failed’ degrees; skin-tight jeans and ties; accents; stories of London and New York; and finally, their disinterest in the rural issues, are not the true representatives of Pakistani art. But the bhands understand this, so does Pamment, that for the international community it is far easier to communicate and promote people who look, speak and think as them. The bhands paint a difficult picture to appreciate. The bhands wants your support, but will attack your manners. The bhand questions religion but also secularism. The bhand wants to be part of the system but will not abide by the civil rules of the society. The bhand conforms to norms but destabilizes them too. The bhand ‘dishes harder truths that might unsettle the neo-imperial paradigms’ (203).

The book is published with Palgrave studies in Comedy, yet Pamment’s work is anything but comedy. It reveals discriminations that the ‘subaltern’ artists face against the bastions of their art. The book tells story of people who used to perform for kings, rulers and ‘common man’ but now fight penury, despair and disillusionment. But it is also a story of people in constant flux and revival, and, in that, one finds hope.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Asad Abbasi has a Masters degree in Political Economy of Late Development from LSE. Currently, he is researching conceptual frameworks of development.

Asad Abbasi has a Masters degree in Political Economy of Late Development from LSE. Currently, he is researching conceptual frameworks of development.

1 Comments