The President of Pakistan, Mamnoon Hussain, recently signed the 31st Constitutional Amendment Bill into law, giving a green light to the merger between Pakistan’s Federal Administered Tribal Area (FATA) and its Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPK). Whilst this has been hailed as a democratic victory, Amber Darr examines the complex legal and political implications of this enactment.

On 31st May 2018, the President of Pakistan, Mr. Mamnoon Hussain, signed the 31st Constitutional Amendment Bill into law, thereby giving a green light to the merger between Pakistan’s Federal Administered Tribal Area (FATA) and its Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPK). The enactment of this bill has been well-received: it is being hailed as a victory for Pakistan’s often unsteady democracy; as a re-organisation and streamlining of its federal structure, and as a harbinger of a new era of development and prosperity for FATA and its citizens. However, the legal and political implications of this enactment are not only more complex but also have a global dimension that extends far beyond Pakistan’s borders.

A Tangled Web

To unravel these complicated yet significant implications it is necessary to understand the geography of the region as well as its tangled history. FATA essentially refers to a narrow strip of steep, rugged and impassable mountains, nestled between KPK and Afghanistan which can only be crossed through one of the several passes that straddle it from east to west. Historically, the region has been synonymous with the Khyber Pass through which countless invaders, from Genghis Khan to the Mughals, entered the Indian sub-continent. In more recent times, however, other areas of the region, such as Waziristan, have also gained notoriety: first as targets of US drone attacks and later as the battleground of Pakistan Army’s operations against militants.

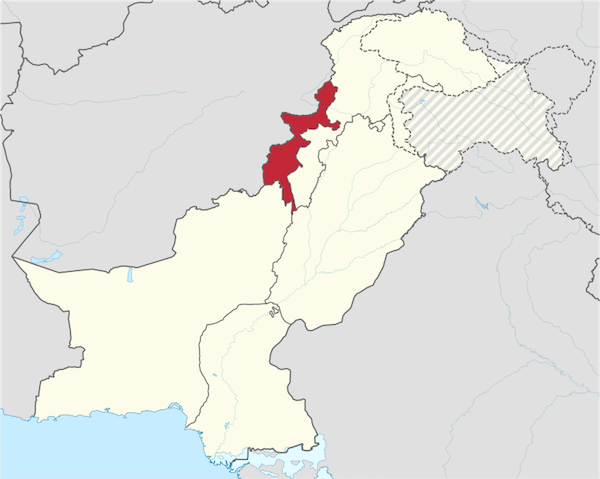

Federally Administered Tribal Area, North West Pakistan. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Federally Administered Tribal Area, North West Pakistan. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.

FATA’s distinctive geography is matched only by the unique character of the Pashtun people that inhabit it. Although, the Pashtun are generally known for their valour and adherence to ‘Pashtunwali’—the Pashtun code of honour—British Colonialists had discovered, much to their dismay, that the combination of these two traits, along with the impact of their terrain, rendered them largely ungovernable. In 1848, the British introduced special laws to administer the region. By 1901 these laws were consolidated as the Frontier Crimes Regulations (FCR) and remained in force throughout British rule. The FCR, although based upon customs and traditions of the region, were seen by the Pashtun as part of the Colonial government’s plan of subjugating them and securing easy convictions.

At the time of India and Pakistan’s Independence in 1947 FATA came under the administrative control of the government of Pakistan. However, it remained politically and legally detached from the rest of the country. In terms of Article 1 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973, FATA was recognised as a discrete constituent part of the federation, which, under Article 247, was to be administered directly by the President through the Governor KPK. Further, in terms of Article 247, federal and provincial laws applied to the region only if the President in his discretion so directed; Governor KPK had the power to make regulations for the ‘peace and good government’ of the region, albeit with the approval of the President, and, most significantly, the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and the High Courts was ousted, unless the Parliament legislated otherwise.

To complicate matters further, Pakistan enacted the Supreme Court and High Court (Extension of Jurisdiction to Certain Tribal Areas) Act 1973 whilst still keeping the FCR in place. FATA, therefore, had two legal systems: one under the Constitution and the other under FCR. The FCR combined the executive and judicial function in the Deputy Commissioner (DC); made fact-finding the domain of the Jirga; dispensed with procedural and evidentiary rules in proceedings, and decreed that appeals from a decision of the DC could lie only to the Commissioner rather than to the courts. FCR, therefore, was contrary not only to the Constitution’s avowed commitment to separation of powers but also to the customs of the region, where historically, the Jirga had not exercised any formal judicial authority.

In time, the FCR came under heavy criticism by the courts (the 1995 decision of the Supreme Court in Government of NWFP v. Muhammad Irshad is particularly significant in this regard) and the civil society. However, this made little difference to the citizens of the region. The people of FATA, worn out by the excesses of the DC and kept legally and politically isolated from the mainstream, had by then found a voice in Maulana Sufi Mohammad and his Tehreek-e-Nifaz-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM) which rejected both the Constitution and the FCR, and called for and established Shariah Courts. It was only in 2009 when escalating militancy had paralyzed the region that President Zardari finally took the situation more seriously. However, even then it took until 2011 for the FCR to be amended and the people of FATA to be granted political rights.

The merger in perspective

Against this backdrop, the FATA-KPK merger certainly represents a restructuring of Pakistan’s federal structure. It reduces the overall size of Pakistan’s Senate and National Assembly; increases KPK’s share, and, integrates FATA into the mainstream politics of the country. The merger also represents a victory for democracy, to the extent that it reflects the combined vote of a number of opposing factions in Pakistani politics. However, it camouflages two important facts: first, that the representatives of the religious, Jamiat Ulema-e Islam (F) and the nationalist, Pashtunkhwa Milli Awami Party had walked out of the merger proceedings and second, that the Taliban, possibly under the leadership of Maulana Sufi Muhammad’s son-in-law Maulana Fazlullah, still operate in the region—indeed, within days of the merger there were reports on social media regarding clashes between Taliban and civilians. These realities suggest that whilst the merger may have been achieved on paper, it may still be resisted by groups accustomed to treating the region as their fiefdom.

These ground realities along with the Pakistani federal government’s poor record of supporting the so-called smaller provinces and the judiciary’s tendency for delay in deciding cases makes one wonder if the merger will bring the much-needed peace and prosperity to the citizens of FATA. The government’s failure to meaningfully integrate FATA citizens into the mainstream or the judiciary’s usual laid-back attitude towards petitions filed before the courts, is likely to create yet another cycle of resentment and unrest within the country—this time, however, the government would not have the option to deploy draconian measures to deal with these situations. Continued unrest in a region historically known for its antipathy towards the west, means a continued cause of concern for the international community. Perhaps the only solution is for the Pakistani government and international powers to collaborate as closely for the development of the region as they have done in the past to fight militancy.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Cover image: Khaledafridi village, Tirah valley, Khyber, Kurram and Orakzai agencies, FATA. Photo credit: Azam Rafique, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

About the Author

Amber Darr holds a PhD in Law from University College London, whee she is a teaching fellow and a Senior Research Fellow at the UCL Centre for Law, Economics and Society. She is also an Advocate of the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

Amber Darr holds a PhD in Law from University College London, whee she is a teaching fellow and a Senior Research Fellow at the UCL Centre for Law, Economics and Society. She is also an Advocate of the Supreme Court of Pakistan.