By signing up to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, Bangladesh is committed to promoting the rule of law and ensure equal access to justice for all. Sarder M. Asaduzzaman argues that Village Courts, a quasi-formal rural justice delivery mechanism, can be the legal and institutional tool to not only improve an overloaded and costly justice system, but help the country meet its international commitments.

Under the Honorable Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s leadership, Bangladesh has signed up to both the Millennium Declaration in 2000 and the more recent SDGs. Having scored well in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), Bangladesh since 2015 has aspired to a similar performance in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). During this time, Bangladesh has taken key steps to try and achieve these targets. A SDGs coordination unit has been established within Prime Minister’s Office, and as part of a systematic review of the implementation of ‘Agenda 2030’, the government organised for the first time a national conference in 2018, in which forty-three ministries and divisions were present, along with a similar number of non-governmental organisations to discuss how Bangladesh could reach these goals.

Constitutional aims, real-world problems

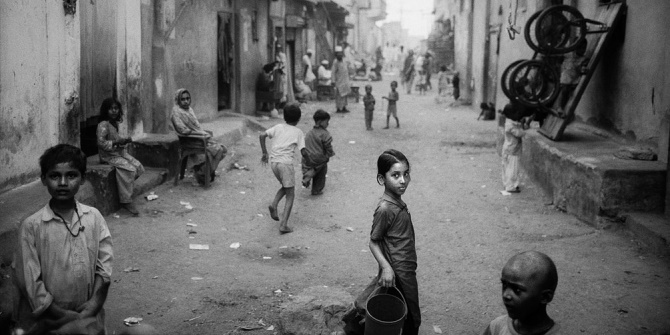

A key element of the SDGs is to promote peace, justice and the strengthening of institutions. Point 16.3 of the SDGs declaration states an aim to “promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all.” Bangladesh’s constitution reinforces this aim, as in Article 27 it states that “all citizens are equal before law and are entitles to equal protection of law.” These legal aims however in reality are not realised: the HiiL study report published in 2018 states that four out of five adults in Bangladesh faced one or more legal problems in the past four years. Another study cites that one in every six households has on-going disputes; among the disputant households 40 percent have disputes that fall within the jurisdiction of village courts.

Photo: Hearing session in a village court | Credit: AVCBII Project, UNDP

Photo: Hearing session in a village court | Credit: AVCBII Project, UNDP

Lack of safeguards

Like many other developing countries, access to justice for the citizens of Bangladesh is not properly safeguarded. The formal justice sector in particular suffers from chronic problems at all stages of the justice delivery system, which seriously limits citizens’ ability to access justice through the courts: the police are understaffed, under-equipped, inadequately trained, the court’s infrastructure is inadequate, the number of judges is too few, and court procedures are slow, complex and confusing and expensive. This has led to cases delayed, often by years. There is currently a backlog of 3.2 million cases.

With 170 million citizens, Bangladesh has only 1,747 judges; and the police-public ratio is 1:816. In addition, a criminal case takes an extremely long time to reach a verdict. Given these circumstances, about two-thirds of disputes do not enter the formal court process. Instead they are either settled at the local level, through informal settlement by local leaders or a village court, or they remain unsettled.

Government Acts and local justice

The government introduced the Village Courts Ordinance in 1976, later replaced by the Village Court Act in 2006, which established a Village Court in each union to deal with a wide range of minor criminal and civil disputes. Village Courts, a unique justice delivery mechanism, employs an easily-understood and simple procedure based largely on shalish (mediation), but modified to address some of the inequalities in the traditional form with a strong restorative justice approach. This mechanism, if properly functional, can significantly contribute to helping achieve the SDG’s goal of “promoting the rule of law.”

Village Courts

The Village Court is made up of a panel of five members, normally the UP Chair, and four nominated Panel members. Two panel members (one of whom must be a member of the UP) are nominated by each party to the dispute. The Village Court is empowered to employ a mix of conciliation, mediation and arbitration to deal with minor civil and criminal matters and may award compensation. The fee associated with Village Courts is extremely low, and parties are not allowed to be legally represented. Village Courts have no power to impose punishment or imprisonment but can order restitution or compensation.

Decisions at the end of an arbitration are legally binding and enforceable and may only be appealed to the District Courts if the panel is split 3:2. They are exempt from normal rules or evidence and procedures, and can be best described as a quasi-judicial local dispute resolution mechanism. As such, they are not within the purview of the Chief Justice, and in fact have no official link to the judiciary although cases (which are triable at Village Courts) are referred from District Courts. The District Court also hears appeals from Village Court’s decisions.

Instead, they fall under the responsibility of the Local Government Division of Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives at the national level and directly under the responsibilities of the lowest tier of local government institutions – the Union Parishad (UP). This means they have the potential to strengthen local authorities and institutions, make them more responsive to local needs, function as a bridge between informal and formal justice institutions and provide a level of affordable, quick and accessible justice for all residents of a UP, particularly the poor, women and other vulnerable groups.

Activating village courts in Bangladesh

It is against this backdrop, that in 2016, the Local Government Division, following a successful piloting (2009 – 2015), with funding from the European Union, the Bangladesh Government and the UNDP, implemented ‘Activating Village Courts in Bangladesh Phase II project’ targeting 1,080 Unions across the country. In just over two years, the project has been a huge success: as of December 2018 a total of 79,568 cases were reported, 61,450 were resolved and where 56,440 decisions or verdicts were enforced. Of those who received justice 28% were women while women only made up 13.5% in the justice delivery process.

In addition, 52% of people believe the Village Court has led to lower levels of ‘fighting and quarrelling’ and 31% believe it has led to less crime in their area. Such satisfaction was also built on beliefs that Village Court services are inexpensive (67%), close to where the users live (67%) and the user get the decision they are hoping for (50%).

The ‘Activating Village Courts in Bangladesh Project’ is directly contributing to SDGs, promoting community-based peace, establishing justice and strengthening local justice institutions. With more support and effort to this project from the national government and international organisations, the long-term future for a strong and effective local justice system in Bangladesh is bright.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Sarder M. Asaduzzaman is the National Project Coordinator of UNDP Bangladesh for Activating Village Courts in Bangladesh Phase II Project. His opinion expressed here does not reflect the UNDP’s views or policies but author’s own. asad_sarder@yahoo.com

Village court is very much needed to dispute resolution in rural level. It is also supportive to reduce case backlog in formal courts all over the country. Thanks to National Project Coordinator of UNDP to lead such a demanding project with his dedication.