Myanmar’s national peace process, simultaneously initiated with the opening of the country and transition from a military regime towards a civilian government in 2011, continues to face multidimensional complex challenges in seeking to end over six decades of conflict. Irena Grizelj (Independent Researcher, Myanmar) explores the role of young people in seeking inclusion in Myanmar’s ceasefire and peace negotiations, and draws on new global research on youth in peace processes, which argues that young people can increase the legitimacy and sustainability of peace agreements.

Photo: Young activists organise peace march in Yangon, February 2017. Credit: Irena Grizelj

Photo: Young activists organise peace march in Yangon, February 2017. Credit: Irena Grizelj

Historically, young people in Myanmar have actively participated in – and influenced – political, conflict, and peace movements within the country. Efforts related to peacebuilding, activism, and public protests have been highly visible over the last four decades: student and youth movements led to dramatic changes in state-level power structures and influenced political changes, including independence from the British colony in 1948, the resignation of General Ne Win in 1988, and the initiation of the 2007 Saffron Revolution. The role of youth in Myanmar’s current peace process has not, however, been studied in detail.

Since the lifting of restrictive laws in Myanmar in 2011, numerous youth organisations, groups and networks have arisen, with an increasingly strong presence of youth-led civil society across the country. Today, youth comprise a significant demographic in Myanmar, as well as large percentages of ethnic armed groups, numerous militias, and the military. Youth, defined as aged 15–35 years old by the Myanmar National Youth Policy (passed December 2017), constitute over one-third of the population, with a national median age of 27 years old, and about 55% are under the age of 30, according to the 2014 census.

Despite the historical legacy of youth movements in Myanmar, young people today have been marginalised into a similar exclusionary and suppressive power structure that Myanmar’s youth faced several decades ago: there are few avenues to make themselves heard politically and formally to influence the decisions that will directly affect the future of their country. Young people further face ongoing security and human rights challenges, with large migration abroad in search of employment and quality education, as well as recruitment into armed groups. Within the peace process architecture, no formal structural inclusion mechanisms exist for youth; neither the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) nor the Framework for Political Dialogue contain provisions related to the inclusion and participation of young people as key stakeholders.

The hidden role of youth in Myanmar’s Ceasefire and Political Dialogue

On the other hand, the peace process architecture has extensively relied on the support of tech-savvy, educated young women and men. Youth organisations – in particular ethnic youth organisations and youth wings of Ethnic Armed Organisations – play key roles in coordination, facilitation, and documentation of the ongoing peace negotiations. Under the (former) Thein Sein administrative government, a series of efforts were made to engage young people in the peace process negotiations. The efforts, often advocated for and initiated by young activists and youth leaders, mainly included ‘youth forums’ and ‘youth dialogues’, aimed to raise awareness of the peace process to the younger generation. However, there was limited feedback and accountability of young people’s voices to shape the formal peace negotiations. This culminated in a boycott of engagement in the peace process by the National Youth Congress, following arrests of student leaders advocating for higher-education reform.

With the election of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in 2015, and commencement of the implementation of the Framework for Political Dialogue, young people could be seen taking active and prominent roles within the National Dialogue process, through organising and engaging in civil society platforms, rather than youth-specific spaces. Yet, as the initial wave of hope that swept across the country tapered, young people face a continued lack of space for meaningful political engagement and dialogue with the government. Many young activists have reverted to former tools of participation and expression, namely demonstrations and political protests on the streets. Youth who have been rallying for peace and anti-civil war sentiment since the start of the resumed civil war in 2011 are now facing legal charges that impede freedom of expression and assembly.

Global research on youth-inclusive peace processes sheds new light

Myanmar is not unique with regards to its exclusion of young voices in political and peace negotiations. Globally, in the last two decades, over 1000 peace agreements have been signed globally, across multiple countries and peace processes. Despite the fact that young people often comprise the majority population in countries with ongoing peace negotiations, no comprehensive studies have assessed the role and impact of young people during, and in the lead up to, peace agreements. A new global policy paper – ‘We Are Here: An Integrated Approach to Youth-Inclusive Peace Processes’, commissioned by the United Nations Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth and launched in July at the UN Security Council – has supported the argument for youth-inclusive peace processes, demonstrating the positive and dynamic roles that young people have taken to shape peace agreements. The paper maps young people’s engagement in peace processes in relation to proximity of the ‘negotiation table’.

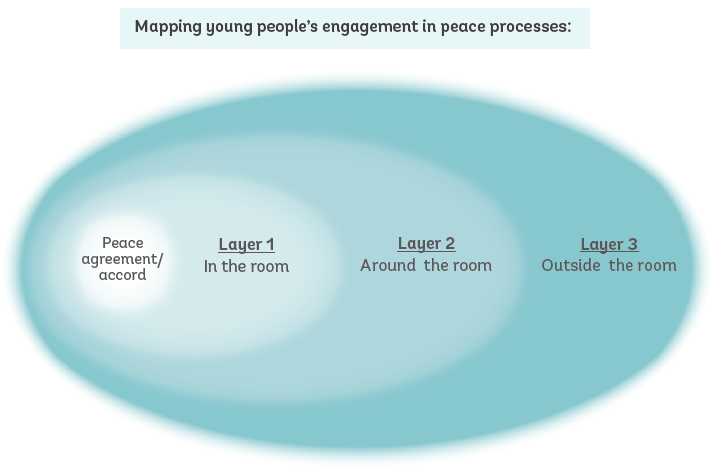

Image: Visualizing the ‘layers’ of youth engagement in peace processes, extracted from report, ‘We Are Here: An integrated approach to youth-inclusive peace processes.’

These layers, ‘in the room, around the room, and outside the room’, should not be understood as a hierarchy, nor do they infer that influence increases with proximity to the negotiation table. Rather, it is important to emphasise and understand that young people’s inclusion and participation across multiple layers of peace negotiations equally matters. Young people’s contributions to influence peace negotiations through creative and alternative avenues, often considered informal, need to be recognised as a critical bridge that shapes and supports formal processes. Utilising a multi-layered and integrated engagement approach should therefore be the main strategy for realising youth inclusion and participation in peace processes.

A rationale for the urgency of youth-inclusive peace negotiations

In Myanmar, history has shown young people to relentlessly demand – with arms or on the streets – in the pursuit of democracy, peace, and state-building. This underscores the importance of linking informal youth participation to formal inputs to the peace negotiations, in order to address structural and cultural conflict drivers. The design and implementation of the Myanmar peace process should enable youth representatives from diverse constituencies to substantively participate and influence the ongoing peace discussions intentionally. Sustaining and implementing peace requires a long-term, multigenerational reconciliation process, which the current young generation will lead in the coming decades.

As peace agreements set the foundation for a society post-war, the political marginalisation and exclusion of youth during this process neglects their needs in society thereafter. Through understanding the role, perspectives, and influence of young people inter-generational ownership of a peace agreement can be garnered. As the next generation of leaders and stakeholders will emerge from the current cohort of youth, their engagement in all stages of the peace process is critical for a democratic and peaceful transition. Myanmar faces an unprecedented opportunity for peace; it’s younger generation must be recognised as key for the peace to last.

This article is based on revisions from the author’s papers, ‘Engaging the Next Generation: A Field Perspective of Youth Inclusion in Myanmar’s Peace Negotiations’ (International Negotiation: A Journal of Theory and Practice; Brill, March 2019), and ‘We Are Here: An Integrated Approach to Youth-Inclusive Peace Processes’ (UN Youth Envoy Office, July 2019).

This article gives the views of the author and not the position of South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Irena Grizelj is an independent researcher and consultant on Youth, Peace & Security, with a focus on youth participation and inclusion in peace and mediation processes. Irena is co-author of the first global policy paper on youth inclusive peace processes, ‘We are Here’. She has been based in Myanmar since 2015, and has published several seminal reports on youth, conflict, and peace-building in the country. Her papers and research can be found on her website: https://www.irenagrizelj.com/.