For nearly five years, Debojyoti Das (University of Sussex) visited the Bay of Bengal to try to understand how local coastal communities were being effected by the climate crisis. Here he explains what his visual ethnography reveals about the everyday life of fishing villages on the coast who live at the mercy of the environmental and social consequences of the climate crisis.

Photo: Villagers use bhot bhoti- retrofitted country boats with double cylender diesel engine to commute between villages in the precarious delta backwaters. Credit: Author

Photo: Villagers use bhot bhoti- retrofitted country boats with double cylender diesel engine to commute between villages in the precarious delta backwaters. Credit: Author

In the 21st century, the health and wellbeing of coastal communities are at risk as climate change events accelerate the frequency of natural disasters. Growing inequalities and displacement are subsequently pushing coastal populations to migrate to cities across South Asia.

The global discourse on climate change has evolved increasingly into a discussion on how communities can adapt to these changing conditions and resilience, both socio-economic and ecological, is a crucial aspect of the sustainability of local livelihoods and resource utilisation. However, we currently lack a sufficient understanding of how costal societies build an adaptive capacity in the face of climate change and global warming.

Some regions of the world and their ways of life will in years to come be radically transformed if not disappear altogether. The region around the Bay of Bengal is one such area where residents are vulnerable to extreme weather. The most conservative projection reported in the International Panel for Climate Change Fourth Assessment (2014) is estimated at 40cm by the end of the twenty first century. More significantly however, the rise in sea levels in the northern Bay of Bengal, combined with warm sea surface temperatures, will result in more severe storms and cyclone activity with accompanying high water extremes, surges and salt intrusion.

Photo: A family of crab catchers and petty peasant who migrated from Bangladesh in the 1970s now settled in Kumirmari village, Sundarbans. Credit: Author

Photo: A family of crab catchers and petty peasant who migrated from Bangladesh in the 1970s now settled in Kumirmari village, Sundarbans. Credit: Author

Threats to the Bay of Bengal

In the Bay of Bengal the magnitude of the consequences of this change is beyond comprehension. Nearly 100 million people will be affected; 10 percent of the fertile agricultural land could be destroyed; farming and fishing livelihood could be completely compromised; and the fragile Sundarbans mangrove forest, with their unique biodiversity, are in danger of disappearing altogether. A rising sea level and reduced production in agriculture pose the biggest threats. Kolkata and Dhaka, whose greater urban areas are home to over 20 million people and rising, face the greatest risk of flood-related damage over the next century. Low-lying Bangladesh is vulnerable to flooding and cyclones in the Indian Ocean, which scientific literature suggests will grow more intense in coming decades. In 1991, a 20-foot storm surge that followed a cyclone killed nearly 140,000 people in Bangladesh and left up to 10 million homeless.

Photo: Young village children working as tourist guide and helpers in boats after the Aila cycle on 2009. Villagers see tourism as a livelihood option due to the salinization of their paddy fields by sea water inundation after the cyclone. Credit: Author

Photo: Young village children working as tourist guide and helpers in boats after the Aila cycle on 2009. Villagers see tourism as a livelihood option due to the salinization of their paddy fields by sea water inundation after the cyclone. Credit: Author

Sundrabans

Sundrabans is a vast forest in the coastal region of the Bay of Bengal which is one of the natural wonders of the world. Located in the delta region of Padma, Meghna and Brahmaputra river basins, this unique forest area extends across Khulna, Satkhira, Bagerhat, Patuakhali and Barguna districts in Bangladesh and South 24 Pargans in West Bengal (India). The Sundarbans is the largest mangrove forest in the world and is the home of the endangered Bengal tiger. It was recognised by USESCO as a Natural Landscape World Heritage site in 1987.

Between 2012 and 2017, I undertook several stints of fieldwork in the delta. My fieldwork photographs engage with people’s everyday struggles with a violent climate, human induced economic activities and the consequences it has on the lives of societies who live along the coast.

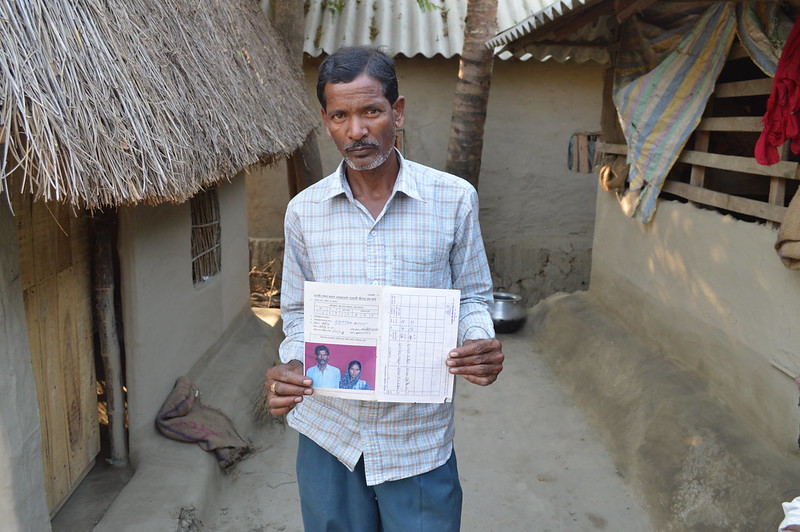

Photo: A village household showing the compensation they received after the devastating Aila cyclone on 2009. Credit: Author

Photo: A village household showing the compensation they received after the devastating Aila cyclone on 2009. Credit: Author

Living in the Sundarbans delta is like walking the edge of a knife. This amphibious landscape is ecologically fragile and exposed to hydro hazards such as tropical cyclones, floods, and typhoons.

These photos offer a place-based understanding of coastal societies in the Bay of Bengal. The photos also focus on the costal seaboard that connects the rest of Asia across the Indian Ocean trade route. When the East India Company and later the British Crown colonized the Bengal delta through the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793, their sole aim was to expand the revenue base of the Bengal Presidency. (The Bengal Presidency was established in 1765, following the defeat of the last independent Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Bengal was the economic, cultural and educational hub of the British Empire in South Asia. It was the centre of the late 19th and early 20th century Bengali Renaissance and a hotbed of nationalist movement. The Partition of British India resulted in Bengal’s division on religious grounds, between West Bengal and East Bengal present day Bangladesh).

European officials who surveyed the region during the later eighteenth century termed the delta archipelago “Sundarban,” meaning “beautiful forest,” in their itineraries and reports. The Sundarbans is a part-land, part-water milieu that supports the world’s largest mangrove megafauna. The liminality of the landscape is marked by vanishing islands that emerge and disappear with geomorphic processes of land formation. In this water-based economy, the riverine communities are socially connected through dispersed village settlements and weekly markets (locally known as haat bazaar). The rivers are not just channels of water; they carry a thriving trade, transporting people, goods, and ideas from one part of the delta to another.

Photo: A tribal village resident in Kumirmari sharing his narrative of rising tides and cyclones. Credit: Author.

Photo: A tribal village resident in Kumirmari sharing his narrative of rising tides and cyclones. Credit: Author.

In recent decades, the lives of communities in the coastal belt have been conceded by state-driven development projects such as the Rampal thermal power plant proposed jointly by India and Bangladesh. The project has triggered several protests across Bangladesh and raised many pressing questions on the environmental sanity of such capitalist and state-driven corporate projects. Meanwhile, the powerful ship recycling industry in Chittagong is creating a massive livelihood crisis in Bangladesh’s Sitakund coastal seaboard, among the traditional fishing community, as toxic litter pollutes the coastal water, and depleting fish catches.

During my yearlong fieldwork in the region, I took hundreds of photographs of the port depicting the defenseless everyday life of fishing villages who live at the mercy of tropic cyclones and ship breaking mafia who grab community owned land to expand their dangerous business. Most of the labour recruits come from the stripped fisherman families who have very little education and have limited opportunities for work and livelihood beyond the toxic ship breaking yards.

The photographs capture their hopes and aspiration for a better future. By contrast in the Indian part of the Sundraban delta communities have opened up their village spaces to the influx of domestic tourists and international backpackers after the devastating Aila cyclone of 2009. Villagers depend on outsiders who visit the island by working as night guards, cooks, porters and open air theater (jatra and pala) entertainers. The inflow of tourists into the delta’s fragile ecology looking to spot the endangered Royal Bengal Tiger has quadrupled. This unregulated entry of boats from Calcutta to Dhaka has caused oil spills which have polluted the pristine backwaters.

Photo: Villagers taking part in a history telling workshop in Kumirmari village. Credit: Author.

Photo: Villagers taking part in a history telling workshop in Kumirmari village. Credit: Author.

The increase in tourists has created a demand for guesthouses, camping sites, lodges and hotels in the delta, generates litter that have added to the vulnerability of the fragile delta ecology. Besides this, shrimp aquaculture, once a thriving business on the coast, has significantly damaged the mangrove forest. Both in India and Bangladesh, human intervention and changing state policies in favour of neoliberalization and globalization have adversely affected the coastal environment.

Photo: A degraded island and nature of river bank erosion. Credit: Author.

Photo: A degraded island and nature of river bank erosion. Credit: Author.

The demand for crab from China, particularly during the Chinese New Year, has added a new transnational dimension to the global interconnectedness of the delta and the demand and supply for seafood in the glocalised economy. The growth in crab export has replaced the booming shrimp aquaculture of the 1980s and has become the new hope of marginal farmers who earn small profits from traders and exporters who manage the demand and supply chain of the business.

These images communicate the community’s everyday struggles with their environment and their aspirations for improvement, local beliefs, customs, festivals, and local tradition. Besides this, the photographs show the connected history of the region—Islamic religiosity that has developed with the expansion of rice cultivation invigorated by Sufi prophets who came to spread the message of Islam from the 12th century onwards. These mystics have been portrayed through scroll paintings by local craft artists known as potuas, which are kept in their community and family-held museum depositaries. While the national and international audiences have been introduced to literatures illustrating the delta’s flora and fauna, the visuals showcasing human societies’ relation with nature and culture have escaped scholarly attention.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

The blog is a short epilogue to the photograph representation of the delta and its vulnerable future that the author featured in five major photo exhibits held at the Indian Museum Kolkata, India 2013; South Asian University, Delhi 2013, Nehru Centre, London 2014; Sussex University 2016; Yale University 2017. The author has used a select group of photographs in this blog from the exhibits.