In Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point, Gyan Prakash challenges historiography that presents the Emergency of 1975-77 as an anomalous period in India’s recent history, instead showing how it grew out of existing political traditions, the legacies of which can still be felt in the present. This valuable analysis not only shows how Indian socioeconomic structures have moulded its politics, but also suggests a way to understand the wider challenges facing contemporary politics in many parts of the world, writes Ben Margulies.

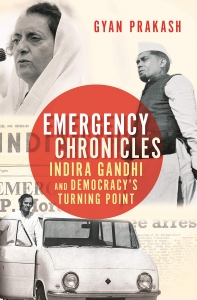

Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point. Gyan Prakash. Princeton University Press. 2019.

It is common in the age of Donald Trump to warn about ‘norm erosion’ – the process where an authoritarian or populist leader defies or undermines the rule of law. Trump’s personalised attacks on opponents are cast as norm erosion as they denigrate the idea of loyal opposition; ditto his threats to, say, re-introduce torture.

Corey Robin, a political scientist at Brooklyn College, often points out on his blog and elsewhere that Trump’s predecessors were not, in fact, great defenders of liberal norms. The George W. Bush administration authorised interrogation techniques that amounted to torture, and one of Bush’s legal advisers became a tenured professor at the University of California at Berkeley; the US military commitment in Afghanistan began two presidents ago. Robin describes ‘the slow delegitimation of American national institutions since the end of the Cold War’, starting with the appointment of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court in 1991:

It continued with the gratuitous impeachment of Bill Clinton, the elevation of George W. Bush to the White House by a Supreme Court deploying the most specious reasoning, a war in Iraq built on flagrant lies, the normalization of the filibuster-proof majority in the Senate, and now the ascension of Trump. ….

Robin’s arguments came to mind quite a bit as I read about the very different context of India in the 1970s, the subject of Gyan Prakash’s excellent Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point. Prakash says that, in most Indian historiography, the Emergency is a sort of blip, when democracy blinked out of existence before its fortuitous restoration. But Prakash uncovers how the Emergency grew organically out of Indian political traditions, and how those traditions continue today. Prakash’s analysis of this political culture, and the way Indian socioeconomic structures mould its politics, suggest a way to understand the wider problems of unruly contemporary politics in many parts of the world.

Indira Gandhi exemplified the Nehru-Gandhi era in Indian politics, when this family dominated the ruling Indian National Congress and a succession of majority governments. Prime Minister from 1966 to 1977, and again from 1980 to 1984, she led a developmental state, committed to the industrialisation and uplift of ‘a population of multiple tongues, regions, religions and cultures’ that ‘had to be fused into a nation’ and made modern (51-52). In the period between 1973 and 1975 Gandhi faced an economic downturn, a mass campaign for her removal led by Gandhian activist Jayaprakash Narayan and a court case that threatened to strip her of office. Indira Gandhi declared a State of Emergency on 25 June 1975. For the next 21 months, she would jail her opponents, muzzle the press, deflect judicial review and wield nearly unchecked executive power, often in tandem with her eldest son, Sanjay.

Image Credit: Indira Gandhi, 1977 (Nationaal Archief, CC0)

Image Credit: Indira Gandhi, 1977 (Nationaal Archief, CC0)

Prakash recounts the Emergency, and Indian political history more broadly, through a series of topical chapters which often sweep down to focus on a particular human drama to illustrate a specific topic. The story of student activist Prabir Prakayastha takes us through the world of preventive detention; the trials of Old Delhi’s walled city serve to illustrate the violent slum clearance and sterilisation campaigns (India saw more than 8 million sterilisation operations in 1976-77 (284)). These are often compelling, though Prakash spends perhaps a bit too much of the book on Sanjay Gandhi and his Maruti project, a failed bid to build a small passenger car in India’s closed market.

Prakash writes that the Emergency’s declaration ‘is […] seen as a sudden irruption of authoritarian darkness and gloom’, and ‘an abrupt disavowal of the liberal-democratic spirit that animated Jawaharlal Nehru [Indira Gandhi’s father] and other nationalist leaders’ (8). One of the key arguments of his book is that this conventional view is wrong: Indian political order always contained ‘authoritarian darkness and gloom’. The Indian National Congress and the Constituent Assembly met in an India mired in ‘backwardness’, new to democracy and riven by an exceptionally bloody Partition. ‘Violence and upheaval were on the minds of the lawmakers’ (56).

Consequently, India’s ruling elites embedded sweeping emergency provisions in the Indian constitution (adopted in 1950), while working to strengthen the central government and limit restrictions on its executive power. For example, the Indian constitution does not require the government to uphold ‘due process of law’ in detaining (or indeed, killing) someone, but merely ‘procedure established by law’ (62-63). India passed its first Preventive Detention Act in 1950 (66-68). Prakash argues therefore that the Emergency was not a departure from Indian norms, but rather an intensification of authoritarian practices New Delhi had employed from independence.

Why were India’s elites, in founding the world’s largest democracy, so illiberal in their habits? Partly it was because they thought it necessary for national development; Indira Gandhi often cited economic development and the fight against poverty as justifications for emergency rule. B.R. Ambedkar, a Dalit scholar often considered a father of Indian constitutionalism, argued that a strong centre and a developmental state were necessary for democracy to function at all, because the state would abolish caste discrimination and level out economic injustice – ‘without equality and fraternity, liberty would be meaningless’ (70).

Prakash’s other great contribution in this volume is to draw on Ambedkar to link the Emergency to a particular sort of elite-society relations. Prior to Independence, India had never enjoyed universal suffrage, so Indian governments were not used to mass politics aside from the civil disobedience and strikes associated with Mahatma Gandhi (who was not related to Indira Gandhi). For mass politics to work, India’s Congress governments would have to create a more prosperous and equal society.

By the late 1960s, it was clear that wealth and equality were not in India’s immediate future. ‘The consequences of this failure are profound,’ Prakash writes (126). Without equality, ‘empowering the disadvantaged can only mean climbing the power ladder rather than kicking out the ladder altogether’, meaning that Indian democracy devolved into a competition between various clienteles and interest groups playing ‘a game of power’, rather than working as ‘an instrument of social transformation to make equality the norm’ (127).

The result is an Indian politics steeped in authoritarianism. Gandhi, unable to relate to the masses through a Western-style mass democratic party, could only handle mass politics through a combination of repression and a cult of personality, trying to create a single pyramid of power and devotion focused on her and her son. On the ground, the opposition developed into a fractious set of warring parties, often based on specific castes or regional bases. These parties managed to unite as the Janata Party to defeat Indira Gandhi when she belatedly – and overconfidently – called an election in 1977, but they soon fell apart (as Prakash details in a chapter towards the end of the book), allowing Gandhi to return to office in 1980.

This leaves secular, democratic India defenceless against its main ideological competitors – Maoist Communism (in the form of the Naxalite revolt) and the Hindu nationalists of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its affiliated parties. The RSS offers a mass politics, but one based on a majoritarian, illiberal and often violent Hindu chauvinism. The Hindu nationalist political camp has long been one of India’s most potent social forces – Prakash details how Narayan’s opposition and Janata depended on Hindu nationalists. Fittingly, Prakash mentions Narendra Modi in his opening and closing chapters.

Perhaps the only unmet ambition in Emergency Chronicles is Prakash’s wish to situate the Emergency and its associated turmoil in the wider history of the post-1968 period. The author hints at this theme a few times, but does not really develop it in depth. This is unfortunate, because many developing polities faced similar stresses during the 1970s, and responded with emergency rule. Prakash alludes here to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s rise and fall in Pakistan, a theme he could have developed more, especially given Pakistan’s own clientelistic, top-down politics. (Anatol Lieven compares India and Pakistan in his book on the latter country.)

That aside, Prakash has written a valuable work, which embodies important lessons and certainly speaks to contemporary issues. Emergency Chronicles reminds us that the horrors of our histories do not emerge from the clear blue sky, but from long traditions of (mis)rule. The book also warns us that democracy is a game played by equals – or else a rigged game, where someone is always threatening to take the ball and go home.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. This piece was originally published on the LSE Review of Books.