Kamal Hossain, who was in prison in Pakistan and flew back with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to Dhaka (via London/Delhi) in January 1972 following the independence and birth of Bangladesh, pens a personal tribute. This blogpost inaugurates a series of specially-commissioned posts to mark the Golden Jubilee of Bangladesh’s independence in 2021. LSE South Asia Centre has created a special logo to mark the occasion, which will appear in all blogposts commemorating this jubilee through 2021-22.

Kamal Hossain, who was in prison in Pakistan and flew back with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to Dhaka (via London/Delhi) in January 1972 following the independence and birth of Bangladesh, pens a personal tribute. This blogpost inaugurates a series of specially-commissioned posts to mark the Golden Jubilee of Bangladesh’s independence in 2021. LSE South Asia Centre has created a special logo to mark the occasion, which will appear in all blogposts commemorating this jubilee through 2021-22.

The Awami League Party had won an overwhelming majority in the general elections in East Pakistan in December 1970. The Awami League had campaigned for a constitutional arrangement based on autonomy of the two regions that comprised Pakistan — West Pakistan (later, Pakistan), and East Pakistan (later, Bangladesh). The elected members of the Constituent Assembly were to meet to formulate a Constitution for Pakistan. As a member of the Awami League, I was actively involved in the movement for political autonomy and independence. I worked with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, or Mujib Bhai as we knew him, and Tajuddin Ahmad, General Secretary of the Awami League, to draft a Constitution that would ensure autonomy for East Pakistan/Bangladesh, and equality between the two provinces of Pakistan.

Instead of allowing the elected political representatives of the people to formulate a democratic Constitution, Yahya Khan had arbitrarily postponed the meeting of the newly elected Constituent Assembly. In protest, Bangabandhu launched a Civil Disobedience Movement in which people participated with boycotts and hartals (strikes). As political tensions mounted (in March 1971) and hartals and curfews brought everyday life to a standstill, Yahya Khan announced talks with the elected political parties on 24 March.

After two days of discussions, Khan abruptly suspended the talks and, on 25 March 1971, the Pakistan military launched Operation Searchlight, a genocide in what was to become Bangladesh. At midnight, the military attacked student residential halls at the University of Dhaka, and shot a large number of students. The students in turn attacked the police headquarters in Rajarbagh, and several newspaper offices. Curfew was declared from the next day; late that night they arrested Bangabandhu from his house in Dhanmandi.

I was arrested on 1 April in Dhaka, and for nine months (April–December 1971) I was kept in solitary confinement in Haripur Central Jail (in the North-West Frontier Province of (West) Pakistan). The most oppressive aspect of the confinement was that I could not communicate with anyone; nor did I have access to newspapers or any other source of information. I knew nothing of the ongoing military violence in East Pakistan/Bangladesh, nor of the Liberation War. Except for one brief meeting, I was not allowed to see my family. The jail officials were under strict instructions not to talk with me nor to give any information about what was happening in the outside world.

Then suddenly, in December 1971, there was tremendous tension in the jail. All lights would be turned off as we heard the drone of planes flying overhead. When I asked why so many planes were flying, the guards gave a careful explanation that a national defense exercise was being held.

After a few weeks the planes stopped flying, and the blackouts ended. I noticed that the jail superintendent’s behaviour seemed more deferential towards me. One day the Deputy Inspector General of Prisons came to my cell and asked me to accompany him in a waiting police car. I was worried about where he might be taking me. He did not tell me where we were going, but I had no choice except to go along with him. We drove through some hilly territory and finally, after a couple of hours, arrived at a police rest house. I was asked to enter. I could not believe my eyes when I found Bangabandhu standing in the front room in the Sihala Rest House in Islamabad. He had been brought there earlier from Lyallpur, where he had been imprisoned. It all seemed miraculous and we were overwhelmed with emotion.

It was only after I was brought to the Sihala Rest House that I learnt that Bangladesh had become an independent nation on 16 December 1971. Bangabandhu told me that Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto had met him at the Rest House, and he had told Bhutto that I should be brought there too. Bangabandhu also told me that we should try to leave for Bangladesh as soon as possible. Bhutto said that their planes could not fly over India, but proposed instead to arrange a flight over Tehran or Istanbul. We thought that since the Government of Pakistan had good relations with Iran and Turkey, these countries could try to coerce Bangabandhu into issuing some kind of political statement. We insisted on flying directly to London. Bangabandhu was tough and very clear. He said he would make no political statements while he remained in Pakistan, and that we could not remain any longer in Pakistan.

I experienced a second miracle during these few days. I was able to reunite with my family. I heard Bhutto telling his Secretary to make arrangements for the plane (on which Bangabandhu and I were to travel) to fly in from Karachi to Rawalpindi. When I heard this, I had a brainwave. I told Bangabandhu that Hameeda, and our daughters Sara and Dina were staying with Hameeda’s parents in Karachi, and asked that they be brought on the plane that was coming from there to collect us. Bangabandhu asked Bhutto to arrange to bring them so we could all leave for London together. That night Hameeda and the girls were put on the plane, and came in it to Rawalpindi airport. It was a real miracle. As I got on the plane, I was hugely relieved to see Hameeda, Sara and Dina there.

We arrived in London on the morning of 8 January 1972. For security, the Government of Pakistan had not announced the flight schedule. London’s Heathrow Airport was informed only an hour or so before we were due to land. Nevertheless, the Foreign & Commonwealth Office had sent Ian Sutherland as a representative of Her Majesty’s Government to meet us at the airport, from where we were driven to Claridge’s Hotel in Mayfair. On hearing the news over the radio that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had been released and was in London en route to Dhaka, large crowds had gathered on the road outside the hotel.

We were informed that Prime Minister Edward Heath was not in the city, but that he would return to meet Bangabandhu the same evening. Later that day, Mr Heath welcomed us at 10 Downing Street and told us that the British government, and he personally, had great sympathy for the people of Bangladesh. In principle Britain had decided to recognise independent Bangladesh, but needed more time to consult with other European countries to ensure a coordinated and simultaneous announcement. Bangabandhu thanked Mr Heath and said he appreciated the support extended by Britain. He also thanked the Prime Minister for the economic and material support extended by the United Kingdom for the reconstruction of war-ravaged Bangladesh. Prime Minister Health assured us of continuing support and asked Bangabandhu ‘What can we do for you?’, to which Bangabandhu replied: ‘Yes, you can do one more favour. Kindly provide a plane to take us to Bangladesh as soon as possible.’ Preparations were thus started to ready an aircraft, and to make sure that Dhaka had adequate facilities for it to land there.

Throughout the day we received many calls from Dhaka. Amongst the first few callers were Tajuddin Bhai (Tajuddin Ahmad, the Prime Minister in exile) and Nazrul Bhai (Syed Nazrul Islam, acting President), who told us about the devastation caused by the Pakistan army, and the genocide.

We were to leave London early the next morning (9 January 1972), and felt that we should use our brief stay in London to meet with the Press, and those who had supported the struggle and were keen to meet Bangabandhu. Rezaul Karim, then acting as the High Commissioner of Bangladesh, arranged for Bangabandhu to meet members of the media at Claridge’s. The turnout was overwhelming and the largest meeting room in the hotel overflowed with people. There was hardly any time to prepare a written statement, but Bangabandhu spoke about our confinement in jail, and about the Pakistan military’s brutality in the war. Amongst the earliest visitors to meet Bangabandhu at Claridges’ were the (Labour) Leader of the Opposition Harold Wilson, along with Begum Abu Sayeed Chowdhury (Abu Sayeed Chowdhury was already in Bangladesh) and Abul Kashem (A.K.) Khan.

Prime Minister Heath had arranged for a Royal Air Force aircraft to fly us to Delhi en route to Dhaka. Early the next morning (9 January) we were driven to the airfield, escorted by S. S. Banerjee, an official from the High Commission of India in London. Amongst the many supporters who had gathered at the hotel was Golam Mowla, the Executive Director of the Great Eastern Insurance Company. He had been a keen supporter of the Awami League, and arranged to accompany us on the flight. Our aircraft landed at the British Royal Air Force Base in Nicosia (Cyprus) for refueling; we all got down and were welcomed by Royal Air Force officers there.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Dr Kamal Hossain en route from London to an independent Bangladesh, at a fueling stop at the RAF base in Nicosia (Cyprus), 9 January 1972, with Golam Mowla on the extreme right and Air Commodore David B. Craig on the extreme left. © For copyright information, please see below.

After an hour’s stop, our plane took off for New Delhi. We understood that there were plans to welcome Bangabandhu at meetings in Delhi and Calcutta, but because we had to fly in to Dhaka no later than 3 pm (before sunset), we apologised for having to put off our stop in Calcutta. In Delhi, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her entire cabinet along with other distinguished citizens had come to the airport to welcome Bangabandhu. We were taken to a large open area next to Palam Airport where Bangabandhu addressed an enormous audience.

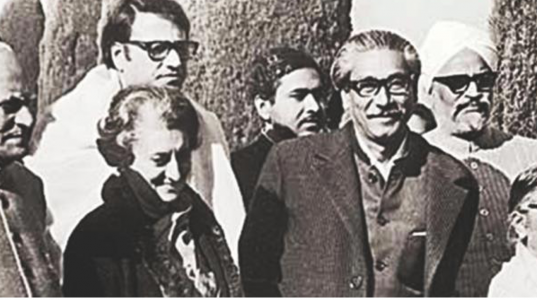

Indira Gandhi, Swaran Singh, and others welcome Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Kamal Hossain (standing behind Bangabandhu) at Delhi Airport, 10 January 1972. © For copyright information, please see below.

We were glad to receive a message from Dhaka that the runway was adequate for the aircraft to land, so no change of aircraft was necessary. Bangabandhu thanked Gandhi and her government for their support for the Liberation struggle in Bangladesh, and their continued efforts to free him from captivity in Pakistan.

As we neared Dhaka, the scene — even from the air — was totally overwhelming. The entire area was flooded with people — political workers, young freedom fighters in khaki, and so many well-wishers. Amongst the first to receive Bangabandhu were Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmad and other senior leaders of the Awami League. Bangabandhu was taken in a truck through cheering crowds lining the road to the Race Course (later Suhrawardi Uddyan) where the mammoth meeting of 7 March 1971 had been held only nine months earlier. In his address to the people of Bangladesh, Bangabandhu expressed an unbridled joy and a deep sense of fulfillment that he was speaking in sovereign, independent Bangladesh.

© Every effort has been made by the author as well as the Editor of ‘South Asia @ LSE’ to identify the copyright holder of the 2 black & white photographs used in this post. LSE South Asia Centre will be happy to acknowledge the copyright holder in future updated versions if it is brought to our knowledge at southasia@lse.ac.uk

© Featured image ‘National Flag of Bangladesh Word cloud Illustration’ by MattZ90 for iStock.

The ‘Bangladesh @ 50’ logo is copyrighted by the LSE South Asia Centre, and may not be used by anyone for any purpose. It shows the national flower of Bangladesh, Water Lily (Nymphaea nouchali), framed in a design adapted from Bangladesh’s dhakai & jamdani textile weaves. The logo has been designed by Oroon Das.

*