The Covid-19 pandemic has created economic conditions that are keeping the stock markets high in India. However, analysing historical trends and current data together, Simtiha Ishaq Mir and Younis Ahmed Ghulam warn that the stock market is out of sync with the real state of the economy and that the government needs to take urgent steps to avoid an uncontrolled and catastrophic bursting of this bubble. The downslide in the markets as the SENSEX lost 1500 points this morning suggests their warning is both timely and serious.

Stock markets have often been used as a barometer of the macroeconomy, with stock market surges representing a booming economy and market crashes heralding an economic downturn. Evidence from the past downturns such as the Great Depression, Japan’s ‘lost decade’ and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 (GFC) finds that stock market bubbles and crashes stimulate macroeconomic upheavals. Similarly, research suggests that fluctuations in macroeconomic factors influence stock market returns.

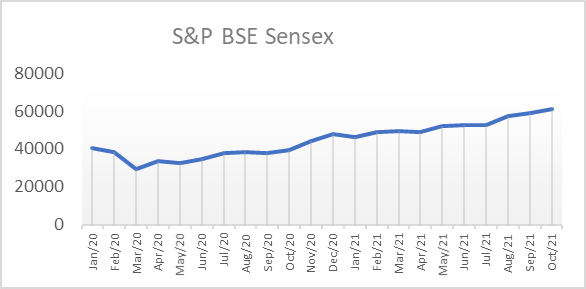

Recently, however, concern has been raised regarding the disconnect between the real economy and the stock markets in India. With the Covid-19 crisis, this discrepancy has become even more prominent. As the crisis developed, the stock market stabilised after an initial decline and then reached new highs in the subsequent quarters (Figure 1).

Figure 1: S&P BSE SENSEX; Source: Data from Sensex.com

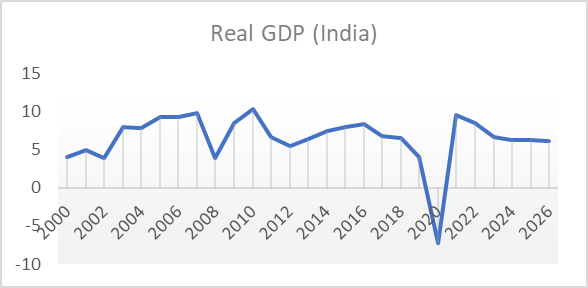

At the same time, the ground realities that emerged were much more distressing as the global lockdown resulted in a collapse of production and economic activity. The IMF has had to constantly revise its forecasts for the GDP in India and the current highs are going to stay unmatched in the foreseeable future with GDP growth expected to fall from 9.5% in 2021 to 6.1% in 2026 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Real Gross Domestic Product; Source: Data from IMF WEO

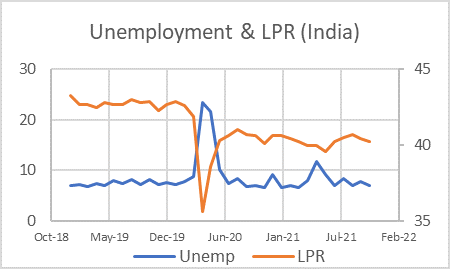

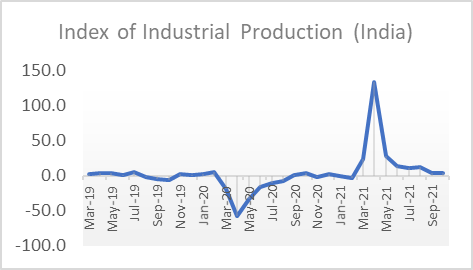

Though the unemployment rate in India is close to pre-pandemic levels, the labour participation rate seems to have shifted structurally, and settled at levels lower than the global average (Figure 3). The Index of Industrial Production (IIP) has also declined significantly after the April 2021 peak (Figure 4). Similarly, the trade deficit for India has also been increasing gradually.

Figure 3: Unemployment and Labour Participation Rate; Source: Data from Cmie.com

Figure 4: Index of Industrial Production; Source: Data from MOSPI

With recurrent waves and new variants of Covid-19 emerging across nations, concerns are being raised as to whether the current exceptional uncertainty will allow the still-optimistic projections of the stock market to come true. Equity returns in the stock market do not align with the state of the economy. Though this divergence is by no means new, the extent of the disconnect this time seems to represent unrealistically high investor expectations about future growth.

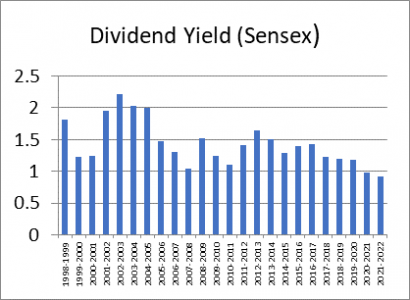

Prominent market analysts such as Warren Buffett and Robert Shiller use valuation measures to gauge the direction of the stock market. Given as ratios, these indicators are used to assess the under- or over-valuation of the market and can be used to analyse by how much the stock market has diverged from the real economy.

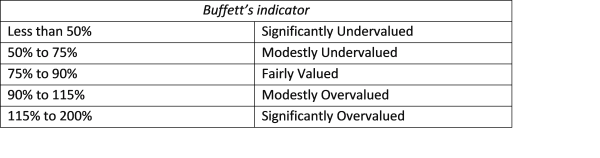

Buffett’s Indicator (the ratio of equity market cap to Gross National Product) gained popularity after the ace investor called it ‘the best single measure of where valuations stand at any moment’.

At 115% and above the indicator shows a market that is ‘significantly overvalued’ (Table 1). For India, the indicator stood at a high of 122% at the end of the third quarter of 2021 (Figure 5), raising concerns for the upcoming growth stability. Similar levels of market capitalisation to GDP were witnessed before the GFC and their recurrence may point to a considerable downside ahead.

Figure 5: Market capitalisation of listed companies to GDP; Source: Data from World Bank

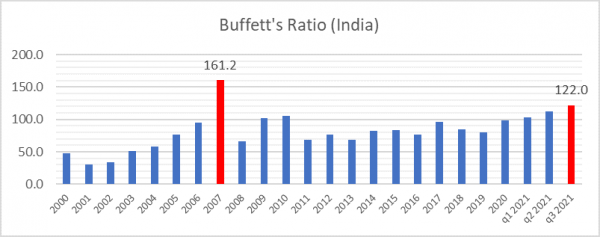

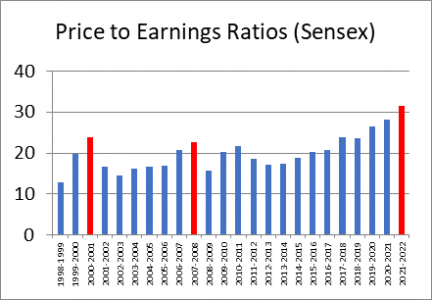

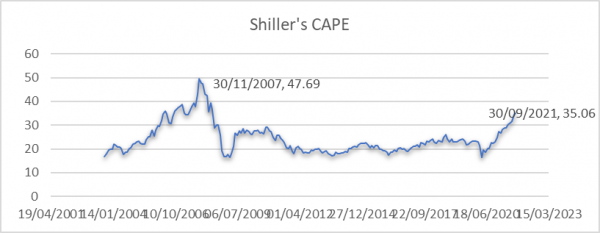

Other indicators also present similar results. The Price-to-Earnings ratio (P/E ratio) is showing an increasing trend in recent years (Figure 6) even though the dividend yield has fallen significantly over the last few years (Figure 7) – both factors indicate an over-valued Indian stock market. Similarly, values for Shiller’s CAPE, whose high values indicate an over-valued market and predict poor returns in future, have been rising over the 10-year average, exhibiting a similar trend as before the 2008 GFC (Figure 8).

Figure 6: Price to Earnings Ratio; Source: Data from BSESENSEX.com

Figure 7: Dividend yield; Source: Data from BSESENSEX.com

Figure 8: Cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio; Source: Data from siblisresearch.com

Thus, all valuation measures are achieving new highs with the conclusion that the Indian stock market is strongly over-valued. The authors believe that there is very little scope left for value-investing in the current Indian stock market.

What’s Causing the Disconnect?

The literature presents multiple reasons for this disconnect: abundant liquidity supported by unprecedented government stimulus, low-interest rates, stock market composition, leveraged buybacks, high volatility and low sovereign yield bonds.

Interest rates, to take one example, have steadily declined in the past few years. In reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic, India’s apex bank – Reserve Bank of India (RBI) – further reduced interest rates to 4%. In general, this indicates that investments in low-risk goods (such as bonds) pay meagre returns and are therefore not in high demand by investors. Even traditionally risk-averse investors have no choice, then, but to invest their capital in riskier shares right now, thereby diverting their funds to equity markets. This is one reason why India’s crucial stock market index – Bombay Stock Exchange’s Sensex – has surpassed the high point of 60,000 even as the aggregate demand in the economy is low.

Other reasons propelling the demand for equity include the growth of the ‘investor pool’ as newbie investors and passive investors enter the market. At the corporate level, the policy of stock buybacks amid a lack of investment opportunities also favours equity markets. Trends in foreign investments also support this rally.

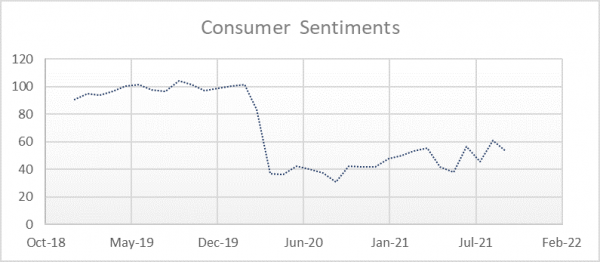

Eminent Economists such as Raghuram Rajan and Abhijeet Banerjee iterate that Indians’ belief in the country’s economic future has diminished in recent years, with the Covid-19 pandemic taking a further toll on consumer sentiment. Though sentiments in October 2021 improved compared to the October 2020 levels, they were still below the pre-pandemic levels (Figure 9). At the same time, though the sentiments in the richer households fared better, the reversal to pre-pandemic levels seems strained.

Figure 9: Consumer Sentiments; Source: Data from cmie.com

Yet, the stock markets seem euphoric regardless of the fact that a reversal of government policies such as the Fed’s taper – slowing down economic stimulus – or simply an increase in interest rates could end this optimistic bubble. All the indicators suggest that this equity bubble is not sustainable in the long run, and market corrections in the near future can bring down both the stocks and the economy. History offers enough evidence to suggest that such bubbles have not ended well, whether in the Panic of 1873 or in the Crash of 2008, bubbles were followed by disruption in the economic activity and financial crisis.

It then becomes pertinent for the government to take into consideration the eventual impact of these stock market exuberance episodes. Ironically, in such instances, the mindset of ‘this time is different’ prevails, leading governments and policymakers to consider the short-term benefits over the long-run challenges of such divergences. The government should urgently focus on framing an optimal monetary policy for the current inflated bubble; they should try to prick or burst this bubble in a controlled manner to prevent the economic and investment distortions of an erratic outburst. For the investors, lump-sum investments should be avoided in the current over-valued markets as the possibility of recovery seems bleak. To quote Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

‘This high yield market resembles a nap on a railway track. One afternoon, the surprise train would run you over.’ (Taleb, 2004)

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude to Professor Bashir Ahmad Joo, their guide and mentor, for his support and insights.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Banner Image: Photo by Dylan Calluy on Unsplash.

This provide great insight about current situation in Indian stock market

Excellent article