The decision to acquire educational qualifications has economic implications. Getting an education demands both time and money and is expected to deliver higher economic returns than the money invested in acquiring it (Return to Education). The recent job riots in India, when some of the rioters expressed a worry that highly-qualified candidates were snatching away low-skilled jobs, underlined this connection. Jie Chen, Sanghamitra Kanjilal Bhaduri and Francesco Pastore use data from India’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) to examine different aspects of this connection.

Between 2011 and 2018, the period on which we focus our analysis, there was a decline in below-primary and primary levels of education in India (see, Figure 1 below). However, there was an increase in middle, secondary, higher secondary, graduate and post-graduate levels of education, which was particularly apparent for the young cohort (24–35 years).

Inadequate Demand

This increase is, however, not complemented by the demand side as official statistics (Statista, 2019) show that graduates made up the highest unemployment rate at16.3% in 2019, followed by individuals with a post-graduate degree or above at 14.2%.

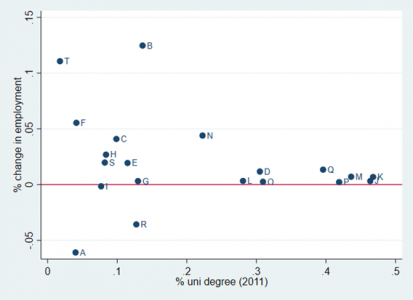

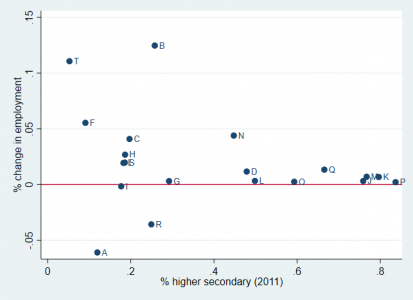

Indeed, the evidence seems to suggest that the 1990s’ push in favour of a higher demand for skills has come to a standstill in more recent years as seen in Figures 2a and 2b. Each dot in the figures represents an industrial sector. On the horizontal axis we show the percentage of employed individuals holding tertiary (above secondary) education qualifications (Figure 2a), and high secondary education qualifications (Figure 2b), in each sector in 2011.

On the vertical axis, we show the change in the employment rate in each sector from 2011 to 2018.

Figure 2a: Share of university-degree holders vs. change in employment between 2011–2018

Figure 2b: Share of higher secondary degree holders vs. change in employment between 2011–2018

Notes: A– Agriculture, forestry and fishing; B– Mining and quarrying; C – Manufacturing; D – Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; E– Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities; F– Construction; G- Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; H -Transportation and storage; I-Accommodation and Food service activities; J– Information and communication; K– Financial and insurance activities; L – Real estate activities; M – Professional, scientific and technical activities; N– Administrative and support service activities; O– Public administration and defence; compulsory social security; P– Education; Q – Human health and social work activities; R – Arts, entertainment and recreation; S– Other service activities; T– Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods- and services-producing activities of households for own use. Data are for working age individuals only.

The figures clearly show that the expanding sectors are those employing a low-to-middle share of tertiary educated, for example, mining and quarrying (·B); household employment (·T); and construction sectors (·F). Very few sectors with a low share of graduates, including agriculture, accommodation and food services, and the arts, have experienced an employment reduction over the period considered. The industrial sectors occupying the largest share of individuals with tertiary education lie very close to the 0-line of no increase in employment. Overall, this is clear evidence that

the demand for skills has not increased much over the last decade or so.

Reduced Returns on Education

With the supply of skilled workers increasing, but demand remaining stagnant, the economic benefits of getting tertiary level education are expected to shrink. Our study corroborates this hypothesis. Indeed, we found lower yearly returns to general education for regular workers (5.5%), self-employed workers (2.7%) as well as casual workers (0.6%). This prompts us to observe that for individuals it is not sufficient to merely hold high levels of education. There needs to be a concurrent increase in the jobs for higher education levels, otherwise returns to education in general decrease.

Moreover, our estimates suggest that over the last about 15 years, returns to education have reduced for higher education in India. Our results show that for regular workers, compared to those with no formal education, one additional year of literacy education increases yearly return by 2.3%, primary education by 3.4%, middle school education by 3.7%, secondary school education by 4.5%, higher secondary education by 5.8%, graduate and diploma by 9.8%, and postgraduate and above level of education by 8.2%. These rates are lower than previously found. Similar patterns are observed for self-employed workers, but casual workers do not seem to benefit as much from education.

Other Trends

We also found a widening of the wage distribution and a number of mention-worthy differences across social groups, sectors, locations. Returns to middle-school and above level of education are higher for women than for men at 28.4% vs. 19.3% at middle-school level; 38.0% vs. 28.6% for secondary; 58.7% vs. 38.2% for higher secondary; 101.5% vs. 59.9% for graduate and diploma; and 119.0% vs. 71.7% for postgraduate and above. There is a gender gap in returns to education in favour of women, with increasing educational levels.

Returns to graduate and above level of education are higher for urban than for rural workers. On completion of graduate and diploma levels the returns are 74.3% vs. 62.3%, and for postgraduate and above level of education the returns are 89.4% vs. 75.1%.

Returns to workers in the public sector are higher than returns in the private or third sectors, especially so for higher levels of education – 38.3% vs. 30.0% for secondary; 58.3% vs. 36.6% for higher secondary; 78.5% vs. 68.1% for graduate and diploma; 94.6% vs. 84.5% for postgraduate and above.

Returns to the scheduled tribes are the highest across all the castes at 21.8% for literate level; 21.0% for primary level; 40.7% for middle education; 48.0% for secondary level; 65.8% for higher secondary level; 79.4% for graduate and diploma level and 91.2% for PG and above level.

Returns to technical degree in engineering/technology are the best (42.6%) for regular workers and among those with technical degree in engineering / technology, self-employed workers enjoy better returns than regular workers (54.1% vs. 42.6%).

Policy Implications

Our finding that education level below primary has the lowest return implies that universalisation of elementary education alone will not suffice in the Indian economy and hence our policy suggestion is that there is a need for improving secondary and above education levels too. In rural areas and peripheral regions, it is important to increase basic levels of education, but in urban areas and for some vulnerable groups like women and scheduled castes/scheduled tribes, it is imperative to improve tertiary education, to enable them to reap the benefits of higher returns. In a developing country like India, returns to education in the labour market may be of limited use because most of the workforce does not participate in the formal labour market. Hence,

a policy of solely increasing education among masses is insufficient if not complemented with other changes in the Indian economy to promote widespread wage employment.

Also it would be important to promote regular employment, as a means to guarantee better-paid jobs to the largest number of individuals and better wages for women.

Banner Image: Photo by Adeolu Eletu on Unsplash.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.