Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is particularly high in Bangladesh and seems to have been made worse during the COVID-19 pandemic, even though Bangladesh ranks first in South Asia in reducing gender gaps. Laila Rahman, Janice Du Mont, Patricia O’Campo and Gillian Einstein took an ‘intersectional’ approach – examining the interplay of several factors working together to keep IPV alive – and present their main findings below. They argue that effective implementation of gender-equity measures, coupled with a high quality of education rather than its mere spread, would put women in the driving seat for the creation of a gender-equitable and violence-free society.

No country is immune to intimate partner violence (IPV) against women, but its prevalence varies across countries. According to World Health Organization’s 2018 estimates, among nine South Asian nations, Bangladesh stands next to Afghanistan with the second highest current physical and/or sexual IPV prevalence rate (23%) among ever-married 15–49 years old women. The latest Bangladeshi national survey shows that almost one in two currently married 15 years and older women has experienced physical IPV in their lifetimes while one in five women has experienced IPV in the past year.

Who are these women?

Women bearing the brunt of IPV, in fact, come from all walks of life. The IPV literature suggests that married women living at the margins – for example, women who are younger, lower-educated, or poor – are more likely to experience IPV compared to their older, higher-educated, or nonpoor counterparts respectively.

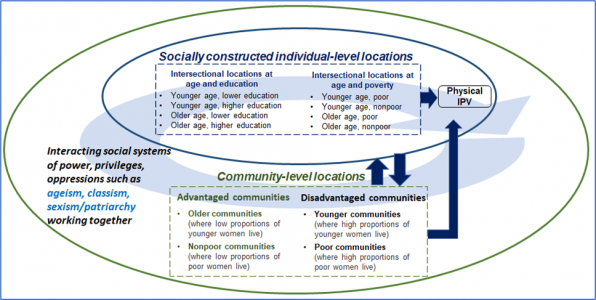

However, in this conventional framework, the impact of different ‘social locations’ (e.g., the ‘location’ of age or the ‘location’ of education) is considered additively – one by one, in a mutually exclusive manner. Intersectionality theory, rooted in Black feminism, challenges such an additive standpoint. This is because no woman lives in just one isolated social location, i.e., experiences life only as a young woman or only as a poor woman, rather than as a young and poor woman. Different structures of power such as ageism, patriarchy, and poverty affect a woman in interaction with each other. For this reason, intersectionality theory invites us to examine ‘intersectional groups’ of women – that is women experiencing two or more disadvantages that interact with each other – and interrogate the various structures of power that interact to create conditions for IPV against women (see, Figure 1).

Therefore, in a recent paper, instead of juxtaposing lower vs. higher educated or poor vs. nonpoor women, we used intersectionality theory to examine whether women located at different intersections of the three factors of youth, education and poverty fared differently in experiencing IPV in Bangladesh (Figure 1).

In addition, we looked at communities in which women live, as IPV literature (e.g., O’Campo and colleagues) suggests that women in disadvantaged communities (e.g., those with high levels of unemployment and poverty) experience high rates of IPV.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework depicting women’s intersectional individual- and community-level locations, shaping their experiencing physical intimate partner violence (IPV). Source. Open Access article by Rahman et al., 2022, figure published under Creative Commons licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

We applied McCall’s intercategorical intersectionality approach to the 2015 Bangladesh Violence Against Women Survey data. Our sample comprised 15,421 currently married women who were living with their spouses during the survey across 911 communities.

What did we learn?

Overall, 25% of women reported experiencing physical IPV in the past 12 months. Counter to our intuitions, we found no evidence that probabilities of physical IPV experiences increased or decreased by the mere fact that a woman lived in a disadvantaged (high proportions of younger or poor women) or an advantaged (high proportions of older or nonpoor women) community.

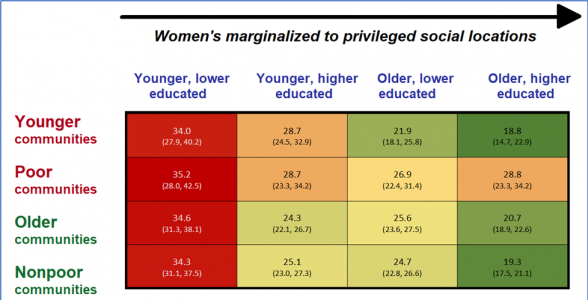

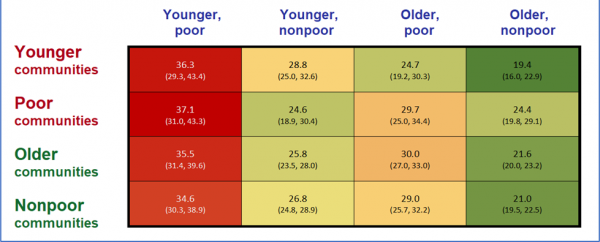

We, however, did find across board that younger women who were also lower-educated or poor had the highest probabilities of experiencing IPV and were, therefore, bearing the brunt of IPV (Figure 2, see 1st and 4th columns).

In terms of ageism, younger women were more disadvantaged compared to older women of same educational levels except, surprisingly, older, higher-educated women had similar probabilities of suffering IPV when living in poor communities. This might happen if getting higher levels of education does not help escaping poverty, while poverty-related stress triggers marital conflict and consequently IPV.

At the intersection of age and poverty levels, younger, poor women faced significantly higher probabilities of suffering IPV compared to older, nonpoor women in all types of communities studied.

Figure 2. Currently married women’s probabilities of experiencing male physical intimate partner violence in the past year across their different intersectional locations and communities, using the 2015 Bangladesh Violence Against Women Survey (unweighted N, 15421). Source. Open Access article by Rahman et al., 2022, figure published under Creative Commons licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Notes. Different colour cells show configurations of differences but not necessarily statistically significant differences. Differences in probabilities between maroon and green colour cells were significantly different at p<0.05 level, but those between maroon and either orange or dark yellow colour cells were not (e.g., probabilities were similar for – younger, lower-educated compared to older, higher-educated in poor communities; and younger, poor compared to younger, nonpoor in younger communities).

Although we did not find differences across groups between disadvantaged and advantaged communities, the disadvantaged communities revealed an interesting pattern. In younger communities, among different intersectional groups of younger women, those who were higher educated or nonpoor did not have any advantage over their lower educated or poor counterparts (Figure 2, see 1st and 2nd columns). In poor communities, having a higher level of education did not offer younger women better chances against IPV but having better access to material resources (being nonpoor) did.

What do these findings mean?

These findings confirm our common-sense expectation that women occupying social locations at the intersections of some marginalised categories have higher probabilities of experiencing IPV.

However, not finding any difference between disadvantaged and advantaged communities was unexpected. Further, the presence of differences within each community type reinforces the need to reach out to intersectional groups of younger, lower educated, or poor women in all communities.

The promise of education for younger women fell flat in all disadvantaged communities and did not protect these women against IPV in either younger or poor communities. In younger communities, where patriarchal norms are stronger, younger women’s access to material resources did not give protection against IPV either, but it did protect them to some extent in poor communities.

The lack of a protective role for education in mitigating IPV points up the fact that the current education system and gender equality initiatives both have to interact with the ageist, patriarchal, and classist economic structures of Bangladesh; to be successful, they must work together as suggested by Schuler and colleagues’ anthropological study.

Bangladesh has come a long way in enrolling girls in schools and reducing gender gaps, ranking first in South Asia. However, access to education alone is not enough. As IPV persists, the country must now focus on enhancing the quality of education that can meaningfully reduce poverty and challenge harmful gender norms without any male backlash. Thus, addressing interacting axes of power might help the country to achieve the sustainable development goals (SDGs), especially SDG 1 for no poverty, SDG 4 for quality education, and SDG 5 for gender equality.

It must also be pointed out that all groups of women including older women in all community types had high probabilities of experiencing IPV. Therefore, intervention programmes must reach out to all women, albeit strategically meeting the challenges and needs of women at specific intersections.

Last, it is important to note that the majority of women at each intersection did not experience IPV. This points to women’s agency in moving along a continuum of resistance leading to prevention and cessation of IPV. Those who experience IPV also make patriarchal bargains through active and passive resistance and negotiating with the systems of oppression. Bangladeshi IPV programmes must therefore put them in driving seats towards building a gender-equitable and violence-free society. Future research should examine intersections of other factors and power structures that impact this crucial issue.

Banner Image: Photo by David Monje on Unsplash .

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.