News of Dalit students being discriminated against, or committing suicide, in Higher Education Institutions across India appear regularly in the media. Deepshikha Sharma and Rama Devi elaborate on how despite long-standing affirmative action policies of the government to help India’s oppressed castes, entrenched social and societal attitudes continue to deny basic democratic rights to them.

In recurrent news headlines, only the names change while reporting the alarming statistics of suicide committed by Dalit students on Indian campuses of higher education institutions (HEIs). Rohith C. Vemula becomes Payal Tadvi who becomes Darshan Solanki; correspondingly, the University of Hyderabad becomes Topivala National Medical College (TNMC) and then the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay.

Repeat and permute a couple of times and in a span of seven years (2014–21) we have a list of 122 student suicides on acclaimed campuses of IITs, National Institute of Technology (NIT) and Indian Institute of Management (IIM), of which 68 students are from India’s (caste)-‘reserved’ categories. These statistics are not empty numbers; rather, they warrant a hard look at the tertiary education system in India and the social milieu in which they function. The fleeting urgency with which the caste question comes to the forefront when a Dalit student commits suicide underlines the collective social–institutional indifference to everyday actions that alienates them from the campuses and the larger polity.

Caste on Campus

The number of HEIs in India has increased from a few hundred (725) at the time of independence in 1947 to 56,205 (including universities, colleges, and standalone institutions (AISHE 2020-21)). Despite this meteoric surge in numbers of institutions, literacy level among Dalits is pegged at 66.1 per cent, far below the national average of 73 per cent (Census of India 2011).

The institutionalisation of affirmative policy through proportional representation guarantees access to and inclusion of Dalits in HEIs funded and administered by the state. The transition to higher education, however, is not effortless; Dalits often lack the economic, social and cultural capital to enter or negotiate these educational spaces (Devi and Ray 2022). Even those who gain entry by proving their ‘merit’ in various stages of ruthless entrance examinations experience insurmountable challenges, hostility and discrimination from their upper-caste peers, faculty and administration who hegemonise these putatively secular spaces to rehearse caste practices. The ‘casteless’ savarnas deploy cunningly innovative strategies to identify the caste of the ‘other’, and curate the information to replicate caste relations in modern democratic premises. In reputed engineering institutions such as IITs where surnames (usually a caste denominator in India) may fail to indicate the caste location of an individual, the JEE rank or the selected branch specialisation becomes a proxy for caste identity. Dalit students pursuing postgraduation and doctoral studies from the central universities say that the administration — staffed by the upper castes — tends to identify the caste location based on the scholarships (like the Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship (RGNF; now titled ‘National Fellowship for Higher Education for ST Students’) for Scheduled Castes (SC)/Scheduled Tribes (ST)) that are awarded to them.

The difficulty to communicate and write in correct English aggravates the already arduous struggles of new beginnings on campuses. Instead of easing the disadvantage arising from the lack of linguistic capital, teachers leave them to understand lectures delivered in English, and grapple with writing their dissertations/examinations in English. This singular focus on the use of English language inevitably results in the production of inarticulate arguments & writing which becomes the basis for repeated rejections by teachers/supervisors, leading to delayed submissions or abandoning the research altogether. There have been reports that faculty members in public universities are prejudiced against Dalits, and adopt a patronising attitude, devaluing the abilities of Dalit students by labelling them as ‘category/quota walas’, referring to their admission through places reserved for them (hence ‘category’,’quota’) as part of the government’s Reservation Policy, thus implying their achievements are undeserved and inferior. Some are outright discriminatory, asking for segregation in seating arrangements. Through derogatory references like ‘sarkari damads’ (government sons-in-law), ‘sarkari Brahmins’ (government Brahmins — the Hindu upper caste) or ‘quota students’, Dalits are repeatedly reminded and humiliated for their caste. The disparaging remarks and humiliation meted out to students adversely and often irreversibly impact the formation of their self-image, resulting in self-doubt and low self-esteem. Educational achievements are undermined and attributed to external factors like affirmative policies, and failures are internalised. Where the support of Dalit professors is available, they too are fighting their own battles, harassed with the threat of revoking their PhDs or being denied promotions.

Further, private HEIs claim to be founded on the principles of ‘merit’ and ‘efficiency’, and are not bound by the commitment of affirmative policy. Disregarding the role in creating educational disparities based on class–caste status, they firmly hold that social identities are impertinent, and educational premises are casteless. A middle-class Dalit student studying in a famed private university in Delhi NCR said that while nobody enquires about caste, in candid moments, in banter and in conflict situations, caste-based slurs are hurled with ease; sometimes, residential location (in the city) can become a means to uncover caste status. The humiliation hurled through caste slurs or probing residential location are a constant reminder for Dalit students of who they are, where they belong and how should they behave. Once identity is ascertained, Dalit students are met with apathy, condescension and inexplicable administrative delays in receiving scholarships, the allocation of a dissertation supervisor, to disparaging remarks under the garb of casual ‘jokes’.

Such implacable environments make it difficult for Dalit students to inhabit and share common spaces with those who are dismissive of their intellect and academic triumphs. The differing forms of humiliation and hostility drive them away from participating and engaging with the socio-cultural diversity of campus life resulting in self-segregation by ‘choosing’ to live among themselves. Often relying on the archaic notion of inherent (caste-based) merit, Dalits students are driven to take the extreme step of suicide by such not so (in)visible systemic forces operating routinely, which is dismissed by the authorities as a consequence of the student’s incapability of handling academic pressures. Repeated aggravations lead students to internalise such devaluations which sometimes erupt as drop-outs or suicides.

Institutional accountability has improved when compared to the Thorat Commission dismissal of 2006 with the establishment SC/ST cells, equality cells, and language labs that help give remedial English lessons to those who feel like they need it. But there are covert ways in which caste discrimination continues to operate on HEI campuses, till overt attempts result in losing an important voice from the crowd.

Democracy Denied

In 1942, at the All-India Depressed Classes conference, the intellectual and chief architect of India’s Constitution, LSE alumnus Dr B. R. Ambedkar gave one of the most revolutionary slogans: ‘Educate, Organise, Agitate’. He conceived education as an emancipatory tool for Dalit Bahujans to challenge and annihilate the oppressive caste structure that institutionalises violence and inflicts indignities on them. The significance assigned to education is in tandem with his vision of realising a just and equal society based on democratic principles recasting people into rights-based citizens.

Educational institutions are hailed as sites crucial to instil democratic conscience through passionate engagement and debate with diverse ideas, and promoting critical thinking. However, despite affirmative policies, and committees to ensure respectful representation of Dalit students, the Indian university system seems to be malfunctioning voluntarily in this matter. Voices are dismissed and silenced, coercing Dalit students into self-exile. Their retreat into oblivion robs the polity of diverse viewpoints that layer and complicate conversations about rights, equality and justice interlaced with a meaningful democracy.

*

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the views of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please click here for our Comments Policy.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

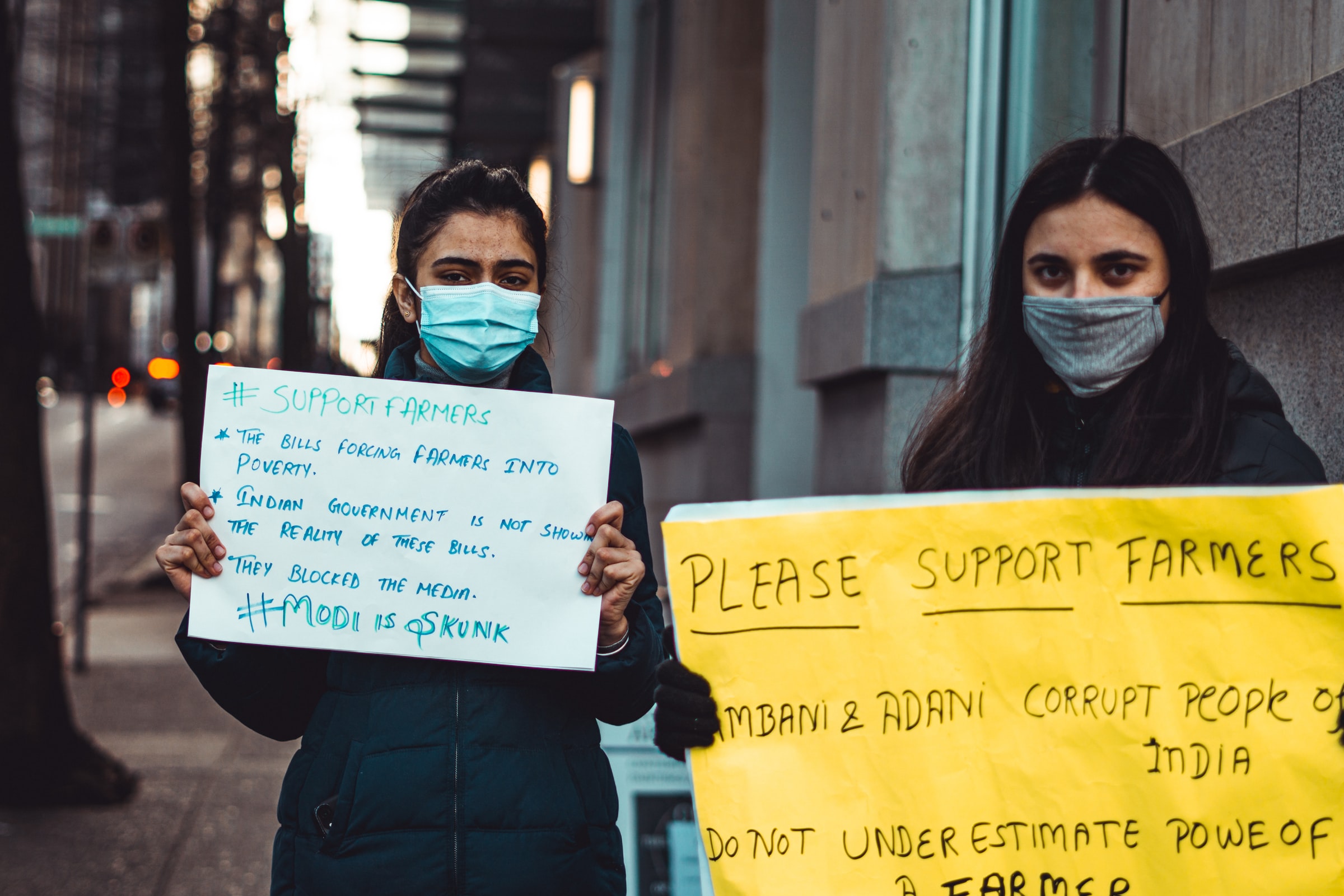

Banner image © Rashtravardhan Kataria, New Delhi, 2021, Unsplash.

*

1 Comments