Climate disasters are increasingly common in South Asia, and Bangladesh is impacted by them. In this post, Tohura Moriom Misti and Shuva Das study one district regularly affected by climate activities, and argue that extreme weather conditions create socio-economic situations where women become more independent of patriarchal shackles, especially in seasons when male members of the household have migrated to urban centres for work.

Political participation, activism, education, skill development, and ownership of assets are key contributors to women empowerment but there also are other, more nuanced, factors in different socio-economic and geographical contexts. This post examines how climate change and natural disasters can be a catalyst for women empowerment, emphasising two criteria: the income-generating capacity and decision-making power of women within the household.

*

Bangladesh, a Muslim-majority country of around 170 million people and an area of 148,460 sq kms, has been struggling to reduce gender gap and discrimination against women. Women considered independent and empowered often exhibit subconscious mental obedience to or dependence on their male partners/guardians when making crucial decisions in their lives. According to a study of the World Economic Forum (WEF), Bangladesh ranked 71st (in 146 countries) overall with a score of 0.714 in the Global Gender Gap Index 2022; however, in political empowerment, it held the 9th place. It lagged significantly in the ranking of other sub-indices such as economic participation and opportunity (141st), educational achievement (123rd), and health and survival (129th) — Bangladeshi women encounter more discrimination than men in these three categories.

Regardless, one district (Kurigram, an administrative district-level unit in north Bangladesh) is an unusual example of gender roles in the country. The development, be it infrastructural or economic, of the district is proportional to its numerous remote island-like parts and of successive natural disasters. It has 20 rivers but poor infrastructure impacts its transport and commutation system; it also has the highest rate of poverty in Bangladesh, with 70.87% of its population living below the poverty line according to the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES)-2016 of the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). The current average literacy rate of Kurigram is 64.99% (68.19% male and 61.93% female), which is roughly 9.67% lower than the national average of Bangladesh, and this declines further in more rural areas. People in Kurigram, particularly those living in remote areas, are very vulnerable to natural disasters like floods, river erosion and limited/nature-restricted livelihood options which collectively slow down its overall progress.

Considering these details, we conducted our study in six disaster-prone unions (local administrative units) of Nageshwari upazila (sub-unit of district) in Kurigram: Bamondanga, Bollverkhash, Kachakata, Kaligonj, Narayanpur and Nunkhawa. In total, the six unions have 49,006 females (according to Bangladesh’s 2011 population census). Assuming a prevalence rate of 50% and using a 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error, the estimated sample size was 390 (aged 16–55) after rounding off, and was proportionally distributed in each union. As part of field data collection, 6 Focus Group Discussions (1 FGD per union) with male and female local residents and 14 Key Informant Interviews with relevant experts and authorities were conducted.

Climate Change, Natural Disasters and the Empowerment of Women in Kurigram

Neither the impact of natural disasters nor the preparedness towards them is fully determined by nature; socio-economic and cultural factors of a society are also important. Juran and Trivedi argue that despite gender mainstreaming not being adequately existent in the disaster preparedness spheres of Bangladesh, women perform pre-disaster tasks that contribute to the resilience of a vulnerable community. For example, before the two previous cyclones (Sidr and Aila), women adopted several coping strategies: putting plastic covers on wells to keep off saline infusion, stockpiling firewood and dry food, securing personal ornaments and essential documents, and saving money — demonstrating that women could break traditional patriarchal barriers during crises like natural disasters.

Kurigram shows women’s empowerment in natural disasters (worsened by climate change) that greatly impacts the socio-economic condition of the district which, in turn, forces the men of the household to seek jobs in urban areas to earn sustenance for their families.

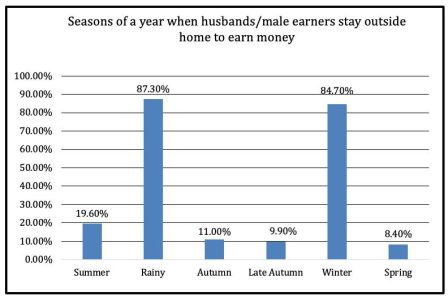

As Figure 1 shows, since the rainy and winter seasons acutely limit livelihood options in Kurigram, a significant majority of husbands of the respondents/male breadwinners of households opt for temporary migration to urban areas for work (87.3% and 84.7% in the rainy and winter seasons respectively). To make matters worse, floods and massive riverbank erosion during the rainy season wash away houses each year. Consequently, many families have to temporarily stay in makeshift houses, without their male breadwinners who move to urban areas to seek employment. Further, the summer season impacts roughly 20% while the rest of seasons (autumn, late autumn, and spring) harm one-tenth of able male earners.

Figure 1: Seasons of the Year when Husband/Male Breadwinners Leave Home for Work © Authors.

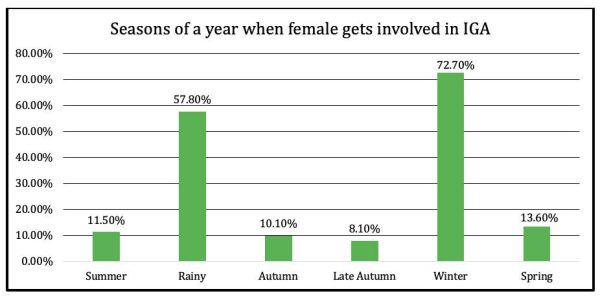

This overall data closely corroborates with those in Figure 2 which shows that around 58% respondents get involved in income-generating activities in the rainy season while approximately 73% in the winter, declining dramatically to 15% in other seasons.

Figure 2: Seasons of the Year when Women are Involved in Income-Generating Activities © Authors.

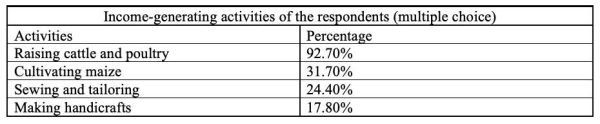

Importantly, the respondents engage in income-generating activities that encompass both masculine and feminine roles, particularly in the absence of male breadwinners in the household. As shown in Table 1, 92.7% of females are engaged in cattle-rearing and poultry, while around a third cultivate maize. Sewing and tailoring have been adopted by 24.5%, and around 18% make handicrafts. These diverse tasks create a more balanced distribution of responsibilities and economic empowerment among both men and women in the region. According to a brief report of the World Bank, bargaining power of women in society augments if they earn.

Table 1: Income-Generating Activities of Respondents © Authors.

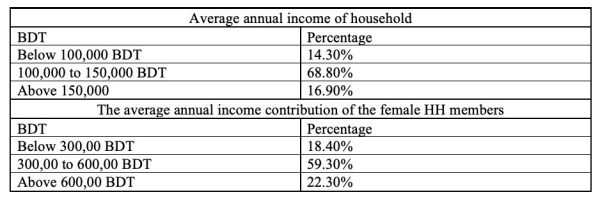

The income-generating efforts or inclinations of women are helpful if their overall household income is compared with their own contributions on an annual basis. As shown in Table 2, most households (68.8%) have a yearly income of 100,000 to 150,000 BDT (US$910–1,365 approx.) whereas those that earn the highest (150,000 BDT+/US$1,365+) make up around 17% of the total. The least proportion (14.3%) earn below 100,000 BDT/US$910. The highest proportion of women (59.3%) annually contribute 30,000 BDT/US$275 to their households whereas 22.3% contribute above 60,000 BDT/US$545. Only 18.4% earn below 30,000 BDT/US$275 for their households.

Table 2: Average Annual Income of Households © Authors.

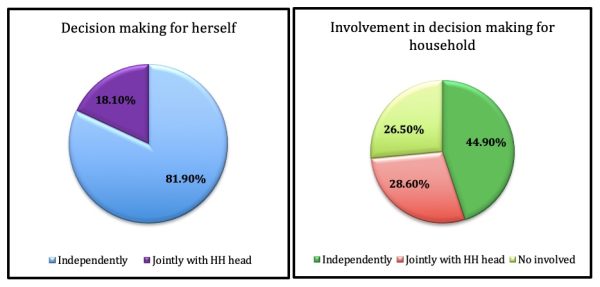

Apart from income by women, our study also considered decision-making powers as a vital criterion for empowerment. Nearly 82% of the respondents said they could independently take any decisions for themselves while around 18% argued that they do so jointly with the head of the household (Figure 3). Regarding decision-making for the household, around 44.9% respondents have independence while 28.6% jointly make decisions with the head of the household (Figure 4); 26.5% are not involved in decision making for the household.

Figures 3 and 4: Decision-Making Powers of Women for Themselves and Households © Authors.

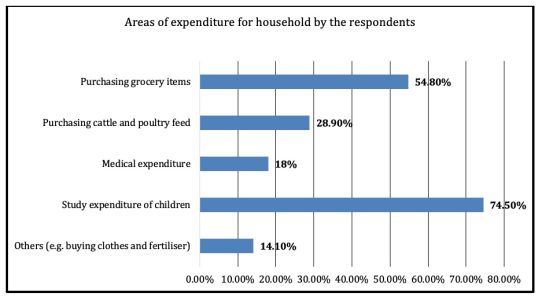

To understand the decision-making capability of respondents more accurately, their freedom of expenditure was also explored. The findings (Figure 5) demonstrate that most respondents (74.5%) can spend the required money on their children’s education. This was followed by a little over 50% who can purchase grocery items for the household, which is almost double the proportion who manage purchasing cattle and poultry feed. The lowest proportion (around 14%) can buy other items (clothes, fertilisers, etc) while just 18% can make medical expenditures.

Figure 5: Areas of Expenditure for Household by Respondents © Authors.

A local woman leader from Kurigram said:

In Kurigram, women have more flexibility in decision-making at the household level since their husbands send a large part of their earnings at home and their wives are mainly responsible to manage the HH expenses during rainy and winter seasons.

This indicates that a seasonal shift in household leadership occurs in Kurigram mainly while the husband/guardian/male head of the family leaves home for employment.

Conclusion

In this post, particular emphasis has been given to challenge the commonly-held assumption that patriarchy always limits the roles of women in the household. The people surveyed were at/just above the poverty line (not luxury or high consumers) where cooperation regardless of gender identity benefits a household. Hence, women can engage in income-generating activities and have freedom of decision-making at the individual/personal and household level in most cases.

The seasonal shift in household leadership from male to female during the monsoon and winter seasons is also a result of limited livelihood options. Moreover, natural disasters provide opportunities for women to challenge patriarchal social norms and empower themselves through organic mitigation measures. This balanced gender role is regulated by nature, not any material forces. To be more precise, the cruelty of nature surpasses patriarchal dominance and maintains gender equilibrium between males and females through engaging both the male and female household members into a cooperative arrangement for survival. Change in weather as well as in the climate influences women to urgently partake the leadership role which has otherwise always been hidden by male dominance.

*

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please click here for our Comments Policy.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

Banner image © Kabiur Rahman Riyad, Kurigram, Bangladesh, 2023, Unsplash.

*