The implementation of forest rights in India has been a complex, and occasionally successful, enterprise. In this post, Tejendra Pratap Gautam examines details of one such successful exercise where community enterprise meets state policy to make it work for communal good, underlining the importance of a ‘political economy’ intervention in development at the grassroots level.

Formal and informal institutions play a pivotal role in controlling, managing and conserving forests and forest resources in India. Whether traditional or state, institutions have actively shaped forest governance by controlling access to forests since colonial times. Even after independence in 1947 and 75 years of development planning, tribals and Adivasis (Indigenous People) continue facing deprivation, with deteriorating living conditions.

Focusing on Gadchiroli district in Maharashtra, this post discusses the consequences of the implementation of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (hereafter FRA), especially on two Blocks (Dhanora and Korchi) in the district. The Act was enacted to undo the historical injustices faced by forest dwellers’ communities. Within the analytical framework of political economy, I look at the interaction of formal and informal institutions in shaping the social and economic choices of people in society.

Since the 1990s, the state has attempted to increase peoples’ participation and decentralise the management of forest governance either by consultation in development planning (such as Watershed Development Programmes) or decentralised natural resource management (through Joint Forest Management Committees under the Joint Forest Management program).

The Story of Dhanora

In Dhanora Block, Mendha-lekha is seen as a model village (of implementation of FRA) since it was the first to receive the Community Forest Resource (CFR) recognition over 1,800 ha of forests in 2009. It recently declared the land (including community-owned and privately-owned) as village ‘commons’ under the Gramdan Act of Maharashtra (1964). It is inhabited by 400 people without much class or caste conflict; all 400 belong to the Gond tribe which has ruled the surrounding forests since times immemorial.

Mendha-lekha was the first village in the country to exercise its community rights to cultivate bamboo under the FRA. Drawing motivation from Mendha-Lekha, around 1,500 villages in the Vidarbha region decided to opt out of traditional governance structures for marketing of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) controlled by the Maharashtra Forest Department (FD), Government of Maharashtra. The district administration is accordingly trying to widen the implementation of FRA by adopting the Mendha-lekha model.

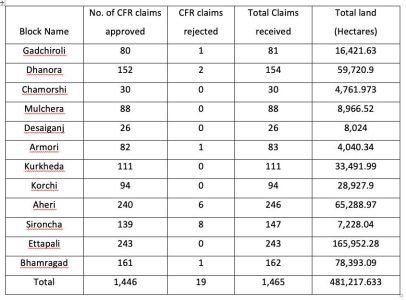

A year ago, in the harsh cold of February 2023, tribals, farmers and other marginalised communities marched from Nashik to Mumbai to demand implementation of FRA across Maharashtra (twenty-one districts of Maharashtra are still untouched by the FRA). In Dhanora, 152 CFR claims have been recognised over 59,720.9 ha of forests. The district administration of Gadchiroli received 1,465 CFR claims; of them, 1,446 CFR claims were approved over 4,81,217.633 ha of forests (see Table 1 for more details).

Table 1: The Distribution of CFRs Claims in Gadchiroli

Source: District Office, Gadchiroli.

While implementation of FRA in Gadchiroli might appear striking per the data quoted above, a very different picture appears across the district. Dhanora, Korachi and Kurkheda Blocks are performing well after receiving CFR; Gram Sabhas have formed Community Forest Rights Management Committees (CFRMC) to manage and harvest NTFP here. As per a 2018 report of the Centre for Science and Environment, 170 villages in the Dhanora, Korchi and Gadchiroli Blocks of Gadchiroli district formed a federation and auctioned tendu (Diospyros melanoxylon) leaves under its banner in 2017, generating INR 17.1 crores in the first year. At the other end, Bhamragad and Etapalli Blocks need help with the post-FRA implementation process which requires forming CFRMC to prepare management plans for CFR-received Gram Sabhas under the FRA. The absence of civil society in Bhamragad block is main reason why even after receiving the CFR, there has been no progress, according to the Tehsildar of Bhamragad (in an interview in December 2019).

Genesis of Maha Gram Sabha: A Democratic Governing Institution

Gadchiroli has a long history of community mobilisation and demand for constitutional rights. This history goes back to the early 1970s when the struggle for rights to guarantee employment, land reforms and protection of customary and traditional forest resources began.

Maha Gram Sabha (MGS) has grown from a long struggle of forest dweller communities against colonial and post-colonial state subjugation. It became a reality through a deliberative process among civil society organisations, social activists, local leaders, forest dwellers, tribals, and Adivasis. According to Izam Shah (a social worker), 87 Gram Sabhas who received CFRs under section 3(1)(i) of FRA came together in 2016, and formed MGS in 2017.

MGS is a democratic governing institution. It has its own formal rules to govern itself democratically. For instance, traditionally, Korchi Block has been divided into ilakas (territories); from MGS’s perspective, Korchi is comprised of seven clusters. Each cluster consists of 10 to 14 Gram Sabhas. To be a member of MGS, each Gram Sabha has to pass a resolution, and deliberate on it in the village. Two men and two women are then selected to be General Body members of MGS. Gram Sabha members have to pay INR 5,000 (US$61 approx.) as annual membership fee to contribute towards covering the operating cost of MGS.

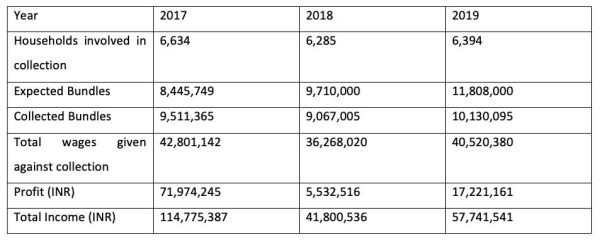

The MGS Executive Committee comprises 15 members, with one man and one woman from each of the seven clusters, including one differently-abled member. Since 2017, MGS has been responsible for harvesting and managing tendu leaves on a large scale without interference from the FD (although there have been instances when the Department did not provide a transport permit or showed hesitancy).

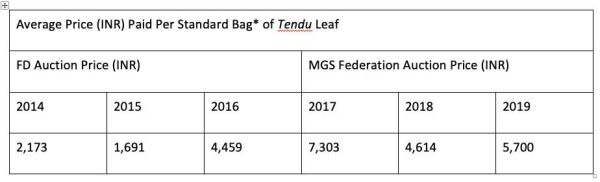

Table 2 shows significant monetary successes of MGS. Table 3 shows the disparity between the prices of tendu leaves per standard bag given to tribals after the FD–MGS federation auction; it is explicit clear that tribals receive better prices (since 2017) in these auctions.

Table 2: Annual Data of Tendu Leaf Collection, Expenditure and Profit

Source: MGS Federation Office, Korchi Block, Gadchiroli; (1 bundle = 70 leaves).

Table 3: Price of Tendu Leaf in Auctions by FD–MGS Federation

*Each standard bag of tendu leaf consists of 1,000 bundles (1 bundle = 70 leaves).

MGS influences the social and economic aspects of tribals’ lives. It gives a space to Gram Sabhas to sell their tendu leaves directly to the highest bidder in the auction. They received the correct price for their tendu leaves, which has increased the average income of household manifold since it was formed.

A recently published article argues that the emergence of MGS in Korachi Block is an example of direct democracy, rendering a counter-narrative of hegemonic and top-down governance systems. MGS has democratised and legitimised the large-scale production and management of tendu leaves after negotiation with the FD and district administration; however, FD has often shown reluctance in transferring power. Such collective institutions emerge from the decolonisation process of the state’s coercive decentralised governance mechanism; it also opens a door for future power negotiations with the state.

The emergence of MGS as an informal institution has provided a shared and collective orientation to the efforts of tribals, Adivasis, and other traditional forest dwellers to decolonise forest governance. It provides a strong economic boost to the marginalised communities, historically subjugated by the colonial state and post-colonial government.

*

This post argues that the political economy of CFRs in Gadchiroli has initiated a new socio-economic churning after the emergence of new bodies like the MGS federation.

*

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the views of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please click here for our Comments Policy.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

Banner image © Tejendra Pratap Gautam, Mahagram Sabha Federation Meeting, Gadchiroli, Maharashtra, March 2022. This photograph may not be used without written permission of the author.

*