What role and value do archives of local and community histories have in the study of transnational and global events, especially in the pre-internet era? In this unique post, Michele Benazzo discusses some such documents relating to the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, and how it enlightens us about the engagement of the diaspora Bangladeshi population in the United Kingdom at the time. This post is part of our continuing series of blogposts highlighting LSE Library’s archives relating to South Asia.

The East End in London is now home to the largest Bangladeshi community in the United Kingdom. But the history of Bangladeshi settlement in Britain, particularly in the East End, is troubled. Bangladeshis had to fight hard, sometimes even violently, to secure their safe presence in the area. The last decade has seen a significant increase in scholarly research on the struggles of Asian minorities in Britain, with Bangladeshis being included. The London East End is the primary setting for these stories, making the history of British Bangladeshi political activism integral to local history. And for good reason too: as the Bangladeshi community relocated in Britain, so did the analytical approach of historical researches.

Yet, focusing on the ‘local’ does not fully exhaust the complexities of Bangladeshi resettlement patterns, in particular to analyse trajectories of political activism. ‘Foreign’ variables, like Bengali politics or the influence of the religious dynamics of Asia, played a role in determining local activism; these factors were acknowledged, but mostly as background detail. In part, this depended on the very nature of research materials available to us. Community and local archives are goldmines for any inquiry on such topics, but they mostly store documents on more recent, rather than long gone, events. Can we then have a global/transnational history of British Bangladeshi political activism using archives designed to mainly hold local documents? Peter Shore’s personal collection in the LSE Library might be a good example.

*

Labour Member of Parliament (Stepney (1964–74), Stepney & Poplar (1974–83), Secretary of State for Trade (1974-1976) and the Environment (1976-1979), Peter Shore (Photo 1) had long been an important political figure in the East End. Interestingly, though, his private letters, drafts of public speeches and newspaper clippings have the fascinating potential to chart hidden transnational trajectories of political activism for an independent Bangladesh in Britain.

Photo 1: The Rt Hon. Peter David Shore, Baron Shore of Stepney (1921–2001) addressing the Bangladesh Student’s Action Committee, London (probably Hyde Park), 1971 © LSE Library SHORE 23/12; please see below for further details.

The war between Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) and (then West) Pakistan in 1971 is enlightening in this respect. In our current hyper-connected world, the ability of conflicts to trespass national borders and mobilise far-distant communities is not surprising. Yet, in the pre-internet/social media era, the struggle of Bengalis in East Pakistan/Bangladesh influenced the resettlement trajectories of fellow Bangladeshis in Britain. A pamphlet (Photo 2) distributed within the Bengali communities of Lancashire and Yorkshire in 1973 to commemorate the Liberation in 1971 proudly says:

During the second week of March 1971, a gathering of some young, like-minded Bengalees took place […] an Association for the Bengalees was formed, mainly to promote the sociocultural interest […] the aims and objectives of the Association seemed [soon] inappropriate, in view of the dramatic events that had taken place […] in Bangladesh. [LSE/SHORE/21/13-British Bangladesh Society]

Photo 2: Cover of Souvenir Brochure 1973 Independence Celebration, Bangladesh and Bangalee Community in Lancashire and Yorkshire © LSE Library; please see below for further details.

The establishment of the Bangladesh Association was initially meant to support East Pakistanis/Bangladeshis living in Britain and yet, an event in faraway South Asia drastically impacted the founding spirit of the Association — from service-provision mainly to lobbying, campaigning and raising awareness of the cause of a Bengali nation. President Abu Sayeed Chowdhury himself remembered how ‘in those days of helpless uncertainty for Bangladesh, the overseas Bengalees too fought as highly effective rearguards in the war of liberation.’

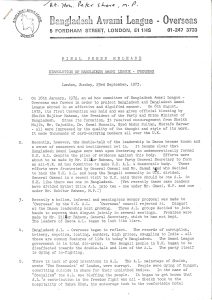

Transnational links vary in time, though. For instance, in a private letter, the leaders of the Awami League-Overseas (UK branch) informed Peter Shore about the dissolution of their organisation in the UK. After having led the Liberation War in 1971, the Awami League became the ruling party in Bangladesh until 1975 when its leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated. Events in Bangladesh flowed into the politics of the British Bangladeshi diaspora once again, this time the other way round: ‘On 16th January 1973’, recalled the leadership of the Awami League in the UK, ‘an ad hoc committee of Bangladesh Awami League-Overseas was formed to project Bangladesh and Bangladesh Awami League abroad effectively.’ But some local supporters grew disenchanted because of the Awami League’s political behaviour in Bangladesh: ‘The party itself is dying of in-fighting [and] it is not fit to run a country.’ The disillusionment peaked on 23 September: ‘The Executive members felt it was disgraceful that they should be associated with that shameful name “Awami League”. The organisation is therefore dissolved.’ [LSE/SHORE/21/13, 23 September 1973; Photo 3]. This shows how local and global scales of action have long coexisted in a perpetual pattern but also how certain transnational channels get saliency at the expense of others and vice versa.

Photo 3: Page 1 of the Final Press Release, Bangladesh Awami League – Overseas, 23 September 1973, announcing the dissolution of the Organisation © LSE Library; please see below for further details.

Besides temporalities, the geography of these scales is another interesting variable accessible through community archives. The spillover of the Bangladesh Liberation War in Britain should not be surprising. No immigrant community ever cuts ties with their homeland or country of origin. But transnationalism does not have predetermined patterns. As seen above, the political energy of the War of Liberation deeply influenced first-generation migrants who read it through the logic of nationalism and Bangladeshi pride. But second-generation activists re-coded such a politicisation in the language of Black Power. A pamphlet of the Bangladesh Youth Movement (BYM) circulated in 1978 reveals this transition:

[…] through participation in the Liberation Movement of 1971, a new awareness came amongst the Bangladeshis […] traditional organisations were no longer able to reflect these developments […] the balance of forces […] had irrevocably moved towards the young generation […] the Black Movement in Britain play[ed] a supporting role in this transformation. [Bangladesh Youth Movement, Pamphlet 1978, pp 1-2, Race Relations Archive 01/04/04/01/04/02/2]

Black Power radical ideology originated in the US through the 1960s but soon established a trans-Atlantic connection, especially among British Afro-Caribbeans communities. The study of the transnational links of the Black Power Movement between the US and Britain has gathered momentum in the last decade but, interestingly, has kept the case of British Asians separate from itself. Although in need of further conceptualisation, the possibility of such political siding seems straightforward: the experience of settlement violence the Bangladeshi community faced in the UK was similar to the racist attacks and threats faced by Afro-Caribbeans in Britain and Black Americans in the US. As suggested by Anandi Ramamurthy, over the 1970s the Black Movement could ideologically underpin the actual needs of anti-racist struggles better than national pride and ‘Bangladesh-ness’. ‘People got together and started protesting about the massacre [in Bangladesh]’, recalled Ruhul Amin, a member of the Progressive Youth Organisation (PYO), ‘at the same time [as] all those racial attacks on the street. We felt it was important to defend ourselves.’ [Tower Hamlets Local History & Archives, Recorded Interview, O/BEE/4]. The adoption of Black Power-informed political militancy is revealing of how second generation British Bangladeshi activism remoulded their transnationalism in time. They distanced themselves slightly from the Indian subcontinent and Bangladeshi national identity to enter (at least temporarily) a transnational community of black people, encompassing the African and the American continent too.

*

To conclude, while a local perspective on British Bangladeshi activism is a promising and fertile ground for rediscovering an important past, it also risks blinding us to an in-depth perspective on non-local variables. In this post, I have used the East End as a microcosm for the global. The conceptualisation of global history has long involved using micro-focus to trace macro trends. Yet, despite its ever-growing scholarship, the debate on global history has curiously abstained from dealing with actual archival practices in a systematic way until recently; and when it does do so, global history seems more preoccupied with the limits of existing archives and how to overcome them by tapping into less-conventional historical repositories: monuments, botanical gardens or gravestones, for instance. The contribution of local/community archives to global history is still under-appreciated and in need of further appreciation and scrutiny. The Peter Shore Collection in the LSE Library and the Tower Hamlets Local History Archives provide a useful added value in this endeavour: local archives’ close look at the surroundings might show how and why some elements of local politics become transnational/global or not, and in which directions.

*

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the views of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please click here for our Comments Policy.

For further details about the private papers of The Rt Hon. Peter Shore in LSE Library, see Daniel Payne, ‘Peter Shore & Bangladesh in the LSE Library Archives‘, 20 December 2021.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

Banner image © Cristina Gottardi, 2018, Unsplash.

*