The rising prevalence of social media such as Twitter and Facebook has been hailed by many for their potential to democratize political participation. Jennifer Oser, Marc Hooghe and Sofie Marien investigate whether social media actually enables previously excluded groups to have a greater voice in politics. They find that in terms of online participation, women are as likely to be involved as men, and that young people are also highly engaged in opportunities for political participation. They also find, however, that while there is a distinct group of online political activists, the education and income stratification of that group is just as strong as for any other form of participation.

The rising prevalence of social media such as Twitter and Facebook has been hailed by many for their potential to democratize political participation. Jennifer Oser, Marc Hooghe and Sofie Marien investigate whether social media actually enables previously excluded groups to have a greater voice in politics. They find that in terms of online participation, women are as likely to be involved as men, and that young people are also highly engaged in opportunities for political participation. They also find, however, that while there is a distinct group of online political activists, the education and income stratification of that group is just as strong as for any other form of participation.

From Facebook environmental campaigns in the U.S. to “twitter revolutions” in the Middle East, we hear daily news about the democratizing potential of online opportunities for political participation. Among scholars in this field of study, some have expressed hope for increased equality in the kinds of people who will be mobilized to participate online. This “mobilization” argument proposes that new opportunities for online political engagement may recruit new people, or more diverse kinds of people, to be involved in democratic engagement.

An opposing “reinforcement” argument has also been proposed, however, which states that online participation opportunities mainly offer additional ways for active people to voice their opinions, thereby reinforcing inequalities that have been found again and again in research on this topic – namely that the socio-demographic profile of a person who is most likely to participate in politics is an older man who is highly educated and has a high income. While some have high hopes for the democratic potential of Facebook and other new media, other authors assume it will not change anything fundamental about political stratification and inequality.

We tested these “mobilization” versus “reinforcement” arguments by analyzing whether types of political participants could be identified who specialize more in one type of participation (e.g. online) than another (e.g. offline). To do so, we used a novel statistical technique for this field of study (latent class analysis) to examine whether online or offline “participant types” can be identified in data from the U.S. in 2008.

Two main questions must be asked to determine whether the mobilization or reinforcement argument wins the day. First, is there a distinctive type of “online political participants”, meaning a group of people who are highly engaged in online political acts but less involved in other activities? Second, we ask if the background characteristics of online activists differ in important ways from other types of participants.

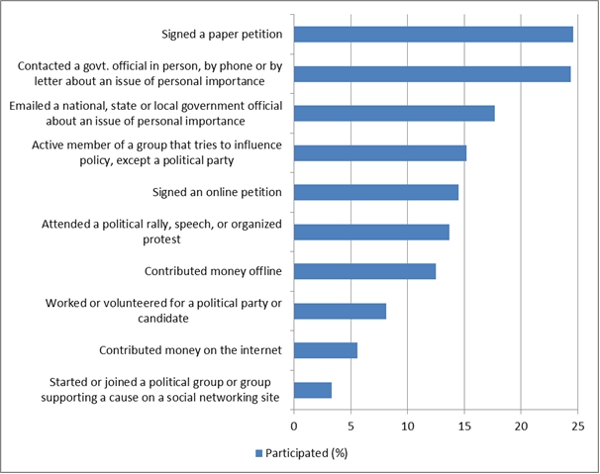

Before turning to the results of the latent class analysis, Figure 1 shows the frequency of various online and offline participation acts in the U.S. in 2008, beginning with the most common acts at the top. This figure shows that even though online political activities are less common than offline activities overall, online acts have become common enough that they must be taken into account in the study of political participation.

Figure 1 – Online and Offline Participation Acts in the U.S. in 2008

Source: Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2008. N=2,551. Respondents answered “yes” or “no” as to whether they performed each act during the previous twelve months.

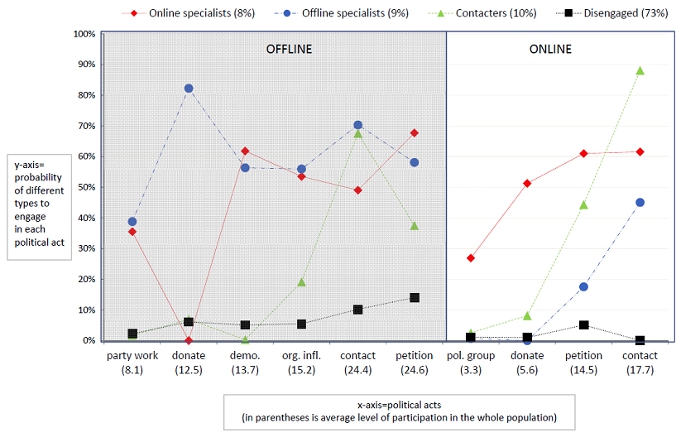

The results of the latent class analysis allow us to differentiate four distinct groups of political participants (Figure 2). A group of “online specialists” (in red) who are particularly engaged in online opportunities of participation make up about 8 percent of the U.S. population in 2008. So there is indeed a group of citizens that is highly active online – but it has to be noted that this group is not as large as is sometimes assumed. We identified two additional groups of engaged citizens: an “offline specialist” group (in blue), that includes about 9 percent of the population and is particularly engaged in offline activities, and a “contact specialist” group (in green) that makes up 10 percent of the population and is active in contacting activities both online and offline.

Figure 2- Four Groups of Participators

The rest of the population belongs to the “disengaged group” (in black), which is unlikely to be involved in any political activity, regardless of whether it takes place online or offline. As scholars argue about the nuances of whether online participation is recruiting new people or new kinds of people, it is sobering to recognize that 73 percent of the U.S. population in 2008 belonged to this disengaged group. Figure 2 also shows that the group of people that specializes in online activities is not totally disengaged from traditional offline politics. We did not identify a group of citizens who are completely disengaged from traditional offline politics but are compensating for this by being active online. Rather, we found that a group of people (“online specialists”) was highly active in online activities but also engaged in some offline activities.

In comparison to previous studies, for those who care about participatory equality these findings give some reason for optimism: instead of the traditional findings that older men are most likely to be politically active, in an era of online participatory opportunities we found women to be as active as men, and that younger people are highly engaged in online opportunities for participation. Yet, an important reason for concern remains regarding participatory inequality: online political opportunities do nothing to change the fact that those with higher education and higher income are much more likely to be politically active than those who are less socio-economically advantaged.

Since we know that those who are socio-economically advantaged have a strong influence in a variety of policy outcomes, the reinforcement of education and income inequalities for online political participants certainly limits the democratizing potential of online participation for changing entrenched inequalities in American democracy.

This blog post is based on article, Oser, Jennifer, Marc Hooghe, and Sofie Marien. 2013. “Is Online Participation Distinct from Offline Participation? A Latent Class Analysis of Participation Types and Their Stratification” Political Research Quarterly 66 (1): 91-101.

Click here to access a publicly available extended summary of the article.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/16mfGOQ

_________________________________

Jennifer Oser – University of Pennsylvania

Jennifer Oser – University of Pennsylvania

Jennifer Oser is a visiting scholar at the University of Pennsylvania and is a postdoctoral researcher on a European Research Council project on Democratic Linkages between Citizens and the State. Her co-edited book, The Political Environment of Policymaking in Israel, was published in 2012 (with I. Galnoor and A. Gadot-Perez, Magnes Press).

_

Marc Hooghe – University of Leuven

Marc Hooghe – University of Leuven

Marc Hooghe is a professor of political science at the University of Leuven (Belgium), and he has published mainly on participation, political attitudes and the democratic linkage between citizens and the state.

_

Sofie Marien – University of Leuven

Sofie Marien – University of Leuven

Sofie Marien is a postdoctoral researcher of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) at the University of Leuven (Belgium). Previously, her work on political trust and participation has been published in among others European Journal of Political Research, European Sociological Review and Political Studies.