As we enter the second day of the U.S. government’s shutdown, many federal employees have been sent home from work without pay, and government contractors and grantees will also start to lose income. Roy Meyers looks at how the U.S government has reached this point, arguing that the Republican Party has not learned the lessons from the previous shutdowns of the 1990s. He writes that further reforms to the budget process are needed and that Congressional legislators need to reject their current short-termism and needless confrontations in favor of making reasonable compromises between opposing ideologies.

As we enter the second day of the U.S. government’s shutdown, many federal employees have been sent home from work without pay, and government contractors and grantees will also start to lose income. Roy Meyers looks at how the U.S government has reached this point, arguing that the Republican Party has not learned the lessons from the previous shutdowns of the 1990s. He writes that further reforms to the budget process are needed and that Congressional legislators need to reject their current short-termism and needless confrontations in favor of making reasonable compromises between opposing ideologies.

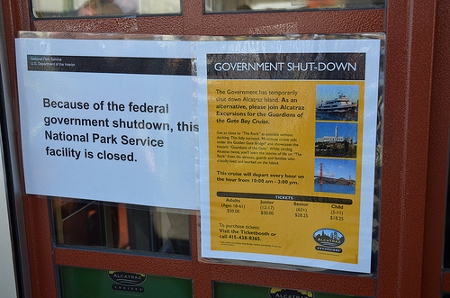

Many federal government employees are now forbidden to work–they may not even answer their government-issued cell phones or reply to work emails. The Congress and President have failed to pass appropriations bills by the beginning of the fiscal year (October 1); the U.S. Constitution requires agencies to receive such funding before they can spend money to conduct basic administrative operations. Some employees have been excepted from this shutdown because of their critical job functions, but they will not be paid until funding is approved.

The economic costs of the shutdown will be large. Unemployment is still high and economic growth is already hobbled by restrictive fiscal policy. Not only will government employees suffer a loss of income, but the agencies they manage will be unable to pay many contractors and grantees, upon whom the federal government relies heavily. It could be worse–entitlement benefits such as Social Security for current enrollees will continue to be paid, and programs financed by user fees rather than general revenues will continue to operate. On the other hand, most agencies have been distracted by planning for the shutdown, and during the shutdown agencies cannot create value for the American people by addressing their core missions. These lost benefits are hard to calculate exactly, but are substantial.

If the shutdown continues for more than several days, this conflict will merge with a more dangerous impasse between the parties–whether to raise the legal ceiling on the federal debt. Absent that increase, by mid to late October, the Treasury will be unable to finance all required payments with current revenues and the borrowing permitted under the current ceiling. The once-inconceivable is now possible–the U.S. would have to default on some of its obligations. The macroeconomic and political effects would be awful.

In 1997, I wrote a short article on the two major shutdowns of 1995-6, which in total lasted three weeks. Frankly, I expected this article to be for the history books, because legislators of the time learned a lesson from that conflict. The Republicans took control of the Congress in 1995, and sought major cuts to spending by refusing to fund agencies at all until President Clinton accepted their demands. Clinton convinced the public that Republicans wanted to eviscerate spending on “education and the environment, Medicare and Medicaid,” and the Republicans were blamed for triggering the shutdown. Though Republicans retained control of Congress in the 1996 election, Clinton won reelection as well, and in 1997 Republicans negotiated over the budget.

It is ironic that Republicans, whose party symbol is an elephant, have a collectively poor memory of what happened during the nineties. House Republicans have forced the current shutdown by insisting that the continuing resolution (CR)–a temporary appropriation bill to fund government when regular appropriation bills have not been enacted–include provisions that are anathema to Senate Democrats and President Obama. The Republicans proposed stripping funds for implementation of the 2010 health reform law and terminating the law’s mandate that individuals purchase health insurance.

While the majority of the public dislikes the law when it is described abstractly, the public also supports most of the law’s provisions. Once the uninsured are able to buy subsidized coverage, public approval is likely to increase. For some Republicans, the shutdown is a last stand in hopes of preventing implementation of a law that should bolster the Democrats’ reputation. Among the ironies here is that before Obama’s election, many of the law’s provisions were suggested or supported by Republicans. Now many Republicans are describing those provisions with wildly inaccurate characterizations.

Much political science research has documented a long trend in asymmetric polarization of the parties, with Republicans having moved farther to the right than Democrats have moved to the left. As the government responded to the Great Recession and following Obama’s election, “Tea Party” forces mobilized. These intense anti-state conservatives helped elect a large group of Republicans in 2010 and 2012 who have effectively ended the possibility that Republicans will regularly compromise with Democrats. The Tea Party members, about a third of the Republican conference, have taken advantage of the House Republican leadership’s support of the “Hastert rule”–the only bills allowed to reach the floor are those that will be supported by a sufficient number of Republicans to pass the House.

There is thus a simple remedy for the shutdown. Speaker Boehner could instead have the Rules Committee send to the floor a “clean” CR–one with no policy amendments from the Tea Party. The majority in favor of passage will comprise most Democrats and the many non-Tea Party Republicans who understand that their party’s strategy is politically foolish. The shutdown will last as long as it takes for those Republicans to insist that their party’s leadership be wiser.

But it would be wrong to consider only the Tea Party at fault for the current mess. Many members of both parties have preferred to blame the opposite party rather than seek realistic compromises. In this hyperpartisan environment, no one in Washington or the country believes the budget process works well. Budget resolutions and appropriations are frequently passed late if at all, the rules of the process are horribly complicated, and the process is not designed to enable intelligent priority-setting and the enactment of far-sighted policies.

Out of understandable frustration, advocates for adopting more sensible policies have in recent years sought alternatives to this “regular disorder.” The 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA), adopted to resolve a previous impasse over raising the debt ceiling, included two special procedures that were intended to be “action-forcing.” It first empowered a “supercommittee” to recommend procedurally-advantaged policy changes. When that committee could not agree, the second BCA provision scheduled large budget cuts, called “sequestration,” that were scheduled for a year later. Inaction over that intervening period let to the imposition of these cuts over a ten-year period, which are widely viewed as being politically unrealistic. Both the House-proposed and Senate-proposed budgets violate legal sequestration ceilings, but Republicans have refused to go to conference in order to negotiate compromise modifications.

There are sensible reforms to the process that could improve it. However, they will not be considered seriously until the vast majority of legislators decide to reject short-term deadlines and needless confrontations–that is, to reattach themselves to traditional norms. These include the idea that effective financial management requires timely passage of appropriations bills. They should also eliminate the counter-productive debt ceiling.

The other neglected norm is that the legislature should be a venue for deliberation. It is now common to hear legislators justify their actions by saying they have listened to their constituents. What legislators also need to do is to listen to each other. By that I don’t mean “listen to your political enemy’s rhetoric so it can be effectively countered.” Rather, I mean “listen to your political opponent’s arguments so opportunities for reasonable compromise can be recognized.” Rather than merely repeat “come now, let us reason together,” they need to mean it.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/18sexIK

_________________________________

About the author

Roy Meyers – University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Roy Meyers – University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Roy Meyers is a Professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. His current research focuses on reform of the federal budgetary process, institutional concepts in budgeting, methods of priority-setting in budgeting and related processes, and attempts to limit earmarks.

2 Comments