The U.S. government has been in a state of shutdown since last Tuesday, and there seems little likelihood of Republicans and Democrats coming to an agreement on funding the government in the next few days. While the government has made it through the previous 17 shutdowns that have occurred since 1977, Andy Langenkamp argues that the threat of the U.S. reaching its debt ceiling in less than two weeks’ time should be of even greater concern. The 2011 debt ceiling fight cost the country billions, and previous technical defaults have also been responsible for recessions and higher borrowing costs. While the markets are still relatively calm for now, if Congress does not come to an agreement on the debt ceiling soon, the country’s economic recovery will be severely at risk.

The U.S. government has been in a state of shutdown since last Tuesday, and there seems little likelihood of Republicans and Democrats coming to an agreement on funding the government in the next few days. While the government has made it through the previous 17 shutdowns that have occurred since 1977, Andy Langenkamp argues that the threat of the U.S. reaching its debt ceiling in less than two weeks’ time should be of even greater concern. The 2011 debt ceiling fight cost the country billions, and previous technical defaults have also been responsible for recessions and higher borrowing costs. While the markets are still relatively calm for now, if Congress does not come to an agreement on the debt ceiling soon, the country’s economic recovery will be severely at risk.

The current US government shutdown – which is more of a government slowdown – isn’t unique: including this one we have seen eighteen shutdowns since fiscal year 1977. Especially between 1977 and 1980, shutdowns were not uncommon: the US had to deal with six of them ranging from eight to seventeen days. From 1981 onwards, the frequency and duration of shutdowns decreased substantially, because the then Attorney General published two legal opinions that more strictly interpreted the law and rules concerning a shutdown which would make sure its implications would be more severe. Between 1981 and 1996, there were nine shutdowns with a duration of up to three days.

Under President Clinton, shutdown time came back in full swing. In 1995/1996 federal employees had to deal with two shutdowns within less than two months, one for a period for five days and the other for 21 days. The shutdowns resulted in the furlough of 800,000 federal workers and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) estimated the costs of the two closures at $1.4billion.

After the federal government closure ended in January 1996, political stability didn’t return immediately: in the first four months of the year, government was dependent on eight continuing resolutions (CRs) to keep agencies going. A CR is what Congress passes when they can’t pass appropriation bills. They started to become common during the 2000s; in 2001 Congress passed more than 20 CRs.

Back to the present poisoned climate

Even if the Senate and House had come to an agreement this time around, the federal government would have been running on a CR that would have expired at December 15 at the latest and possibly even as soon as November 15. Some even spoke of the possibility of a two-day funding extension. But Speaker Boehner felt cornered by the Tea Party wing of his party and chose to not make a deal.

Since the rise of the Tea Party it’s safe to speak of GOP vs. GOP warfare. The right wing, ideologically driven, conservative base of the party has given Tea Party politicians the courage and stamina to confront the moderate GOP leadership and not back down from fights with both their own party and the Democrats that endanger the US economy and global reputation. The current de facto leader of the Tea Party movement, Senator Ted Cruz, spoke for over 21 hours on the senate floor the week before the shutdown in an effort to prevent the Senate from funding Obamacare and keeping the government operational. The Economist described Cruz’ course as part of a series of ever-more-extreme-political-purity tests in the context of conservative purity politics. This kind of behavior obviously is at home with and fuels a political environment that rewards extremism. Cruz wants to show to the Republican base that his fellow Republicans aren’t up to the job of being real conservatives, so that when the time comes for the Republican presidential nomination contest in 2015/2016, he will be able to make the case that he is the one and only true Republican.

Moderate Republican leaders clearly feel threatened by the Tea Party. The leader of the GOP in the Senate, Mitch McConnell, faces a difficult reelection next year in his home state of Kentucky, where he is in danger of losing his seat to a Tea Party candidate. That’s probably the reason he feels forced to regularly take a more radical standpoint than he would like to take, if his seat wasn’t up for grabs soon.

Doomsday deadline still to come

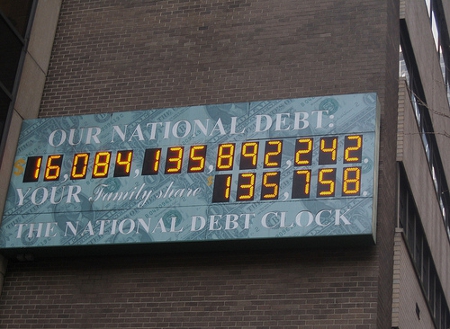

The recent days the fine line between negotiating and extorting have become very blurred and it remains to be seen for how long the public will accept this. The shutdown discussion merely set the stage for an even more nerve-racking deadline on October 17 when the US will cross their debt ceiling. At most the government could get by for another couple of weeks with $30billion cash on hand, but if the White House and Congress won’t reach a deal on raising the debt ceiling, the US will in effect be in default.

Also during the negotiations on the debt ceiling, Republicans will tie raising the ceiling to delaying, defunding, and scaling back Obamacare (important parts of which have started being implemented this month). They will load a debt limit bill to raise the ceiling with $1.1trillion through December 31, 2014 with dozens of conservative priorities which will essentially look like a Republican Christmas list.

Another look at history

What could be the consequences of a bloody debt ceiling fight? In 2011 – the last time there was a dangerous game of chicken being played over the US’ ability to incur government debt – consumer confidence took a serious hit, stock markets cratered, the US credit rating was downgraded, and hiring slowed. The Bipartisan Policy Center has estimated that the 2011 fight cost America $18billion in increased interest payments.

If we go a couple of decades further back, we find that the US did in fact default in 1979. It was a technical default due to some mistakes made at the Treasury department and it only concerned $122million, but that translated into a loss of $12billion. According to some experts the 1979 default has permanently raised the costs of US government borrowing. In 1957, the Air Force stopped paying its bills due to the US hitting the debt ceiling. This amounted to $8billion less spent, the equivalent of 1.7% of GDP. Researchers claim this default was one of the main reasons for the recession of 1957/1958.

Currently, the markets seem calm, and there are a couple of credible reasons for this. They have become used to Congressional brinkmanship, the fiscal position of the US is improving rapidly, and the US housing market is in an upswing. But this – in the words of Democratic Representative Steve Israel – the ‘Congress of Chaos’ has taken the budget battle to the brink for the fourth time in three years and passed that brink this time. What is to say that they will not be so crazy as to let the US default after threatening this a couple of times before?

Global panic?

If politicians can’t reach a deal on time, the US can only spend as much as incoming revenues. That means a 20-40 percent reduction in government spending. It would be surprising if that wouldn’t tip America into recession even before accounting for the resulting financial chaos including potentially quickly rising interest rates. Every week the Treasury rolls over about $100billion in debt. If investors decide they just want their money back, this would result in interest rates rises that could nip the still vulnerable economic recovery in the bud.

We still think that even the Tea Party is adverse to being blamed for making the US a defaulter and according to some legal and economic scholars the law offers President Obama a way out by just plainly ignoring the debt ceiling if Congress doesn’t come to an agreement.

So, a US default isn’t inevitable, but the current unpredictable behavior of politicians will probably cause the markets to show signs of nervousness in the coming weeks. James MacKintosh recently wrote for the Financial Times: “Investors usually hope for the best from Washington until the last minute. Then they panic.” Politico spoke of a “touch-the-stove moment” when writing about the GOP’s handling of the shutdown. The stove will be even hotter within two weeks and it remains to be seen if politicians are prepared to burn their hands even further. If Congress refuses to come to an agreement and Obama refuses to ignore the ceiling, financial markets worldwide will go into cardiac arrest, because financial markets are not set up to trade or finance defaulted Treasuries. The Atlantic calls “not raising the debt ceiling a crisis, if we’re lucky, a historic calamity if we’re not.” Let’s hope Washington will get to its senses and reach a deal before a calamity starts.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/GHh5ti

_________________________________________

Andy Langenkamp – ECR Research

Andy Langenkamp – ECR Research

Andy Langenkamp is political analyst at ECR Research and Interest & Currency Consultants.