More than two weeks into the U.S. government’s shutdown, many commentators are blaming the U.S. Constitution, with its separation of powers, for the political gridlock over the government’s budget and the debt ceiling. Elvin Lim argues that the Tea Party’s factionalism is really at fault – a factionalism that was opposed by the Constitution’s framers. He writes that errant members of Congress need to be reminded that they are part of a chamber of the United States, where the national majority is more important than one single faction.

More than two weeks into the U.S. government’s shutdown, many commentators are blaming the U.S. Constitution, with its separation of powers, for the political gridlock over the government’s budget and the debt ceiling. Elvin Lim argues that the Tea Party’s factionalism is really at fault – a factionalism that was opposed by the Constitution’s framers. He writes that errant members of Congress need to be reminded that they are part of a chamber of the United States, where the national majority is more important than one single faction.

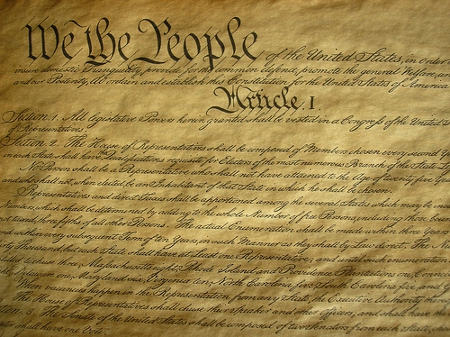

It has become a routine recourse, when examining American politics, for modern commentators to blame the Constitution for the failures of government. We are told that the separation of powers encourages gridlock, and parties pull together what the Constitution pulls asunder. When considering the mess we are in today that is the government shutdown, the truth is closer to the other way round. Parties are the problem, not the solution.

Let’s get down to the nitty gritty, and see if it really is the Constitution that is at fault. Why did Speaker John Boehner refuse for so long to bring a vote to the floor of the House to re-open the federal government? We are told, it is the Hastert Rule, named after Dennis Hastert, which instruct Speakers not to bring a bill to the floor unless it commands the approval of a majority of the majority party in the House.

Well and good, until we consider this indisputable fact: nowhere in the Constitution do we have anything remotely close to codifying the Hastert Rule. The Hastert rule is a creature of modern partisanship; it is named after one man, indeed, it has been denounced by the same man whose name identifies the eponymous rule. Even if the idea that the Speaker should defer to the “majority of the majority” makes sense, it is not to be found in the Constitution.

More importantly, the Tea Party caucus is not a majority of the majority. It is a faction, the vilest enemy to republicanism according to the framers of the Constitution. Or, put another way, the Constitution was expressly created to control faction (by creating a republic so large that no one faction would be able to, at least before the invention of the political party, dominate). Madison could not have been clearer in his opprobrium of faction:

“Among the numerous advantages promised by a well constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction … By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” (Federalist 10)

So when President Barack Obama proclaimed that “one faction of one party in one house of Congress in one branch of government doesn’t get to shut down the entire government just to refight the results of an election,” he was on very firm constitutional ground, and pointedly — I think also consciously — using “faction” exactly as the framers intended it in the eighteenth-century sense. Today’s self-proclaimed “originalists” are picking and choosing what part of history to affirm. “Faction” and “partisanship” were foul words to the framers, for precisely the reasons we are experiencing today. President Obama has no obligation, under the original meaning and intent of the Constitution, to negotiate with a faction; indeed he in on good ground to try to rein it in.

Looking ahead, as Washington veers toward another self-inflicted crisis, raising the debt ceiling, it is useful again, to return to original principles. We are told that the framers of the Constitution created a limited government, and perhaps Senator Ted Cruz et al are right to use Congress’s power of the purse to limit the excesses of government spending. Wrong again. The Constitution was written to provide a more muscular government to pay off the revolutionary war debt. In fact, paying back what the nation owed was at the heart of Alexander Hamilton’s case for the Constitution:

“I believe it may be regarded as a position warranted by the history of mankind, that, in the usual progress of things, the necessities of a nation, in every stage of its existence, will be found at least equal to its resources … A country so little opulent as ours must feel this necessity in a much stronger degree. But who would lend to a government that prefaced its overtures for borrowing by an act which demonstrated that no reliance could be placed on the steadiness of its measures for paying?” (Federalist 30)

There is no way that one can read these words and conclude that the Founders would have been ok with a US government default or any tactic that suggested it as a possibility.

So it is not the Constitution that is at fault. It is faction, injected like a toxin into the Constitution, which has caused the separation of powers to go awry. And if so, the short-term solution for shutdown politics is to call faction what it is. Errant and arrogant members of Congress need to be reminded or educated that while they represent their constituents, some of whom no doubt want a stay on Obamacare, each member of Congress also belongs to a chamber of the United States and it is always the national majority (across the nation) that counts more than a factional majority (in a district). The long-term solution is as simple as it is admittedly inconceivable: if we want to kill faction, we must kill its grandfather and father — the political party and the system of primaries that sprung up in the middle of the twentieth century that has created two generations of extreme ideologues and the era of gridlock. To do that requires neither a dismissal nor a cynical revision of original meaning, but an affirmation of its deepest philosophy — the hope of “a more perfect Union,” sans faction, sans party.

This article originally appeared at the OUPblog, and at the author’s blog, Out on a Lim.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/19PRDw8

_________________________________

Elvin Lim – Wesleyan University

Elvin Lim – Wesleyan University

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com.

It seems that “killing the political party” misses the point a bit and violates some basic rights. Perhaps that is why you label it as “inconceivable”.

I think the only legitimate way to alter or change political parties is for people to get active and involved. That also seems to be but a distant possibility. Certainly changing our election process so that, instead of focusing all our attention on two major parties; allowing their primaries to focus on and define the issues and individuals that are presented to us as important or otherwise; we could demand that the public not fund party elections at all and find ways to open up the field of candidates for our public elections that express more varied positions and encourage more participation. But that would require the current Two-Party dominated process to relinquish its control of the election process itself and that won’t happen easily.

Now changing the rules by which our Constitutionally described Institutions function, rules which are created by the members of those Institutions for their functioning, would go a long way towards what appears to be your goal.

The only way the Rules in those Constitutional Institutions change is when the elected members vote “no” to the continued use of those rules as they are; and adopt others that more accurately reflect the ideals and principles which are supposed to be embodied by these Institutions in the first place.

I’m not holding my breath for that to happen. The rules that have evolved in these Institutions seem to be more attuned to the consolidating and holding on to power than to the real purpose for which the Institutions were created. Your reference to the Hastert Rule is a perfect example.

What I see most prominently in all of this is that the quality and natural traits of men appear to be more base than those traits it was envisioned they would possess by the creators of our Constitution (and they had serious reservations on that mater as it was). The design of our Institutions and the length of terms for our supposedly sagacious and wise elects appear to have failed to override man’s pettiness and narrow self-interests. Statesmanship is in short supply. This would seem to give cause to question many of the bold assertions made by Hamilton, Jay, and Madison as to why this Federal Legislative System, as well as the powers that were delegated to it were wise or even necessary, at least in the form in which we have fashioned them.