Outsourcing public services is not a new concept for the U.S. and state government, but the recent trend towards the privatization of prison services, and the contracts that this entails has caused great concern among some commentators. Shar Habibi looks at the rise of “lockup quotas” in private prisons; quotas where states guarantee that prisons will be filled at rates of 90 percent or even higher. She argues that these quotas mean that even if communities realize their objective of lower crime rates, taxpayers will see no benefit, as they have to pay for prisons as if they were filled to capacity.

Outsourcing public services is not a new concept for the U.S. and state government, but the recent trend towards the privatization of prison services, and the contracts that this entails has caused great concern among some commentators. Shar Habibi looks at the rise of “lockup quotas” in private prisons; quotas where states guarantee that prisons will be filled at rates of 90 percent or even higher. She argues that these quotas mean that even if communities realize their objective of lower crime rates, taxpayers will see no benefit, as they have to pay for prisons as if they were filled to capacity.

In 2012, Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the largest for-profit prison company in the United States,sent a letter to 48 state governors offering to buy their public prisons. CCA offered to operate state prisons in exchange for a 20-year contract that included a guarantee from the governors that the prisons would be at least 90 percent filled for the entire term. In other words, taxpayers had to agree to a 90 percent “lockup quota” or else have to pay for empty prison beds.

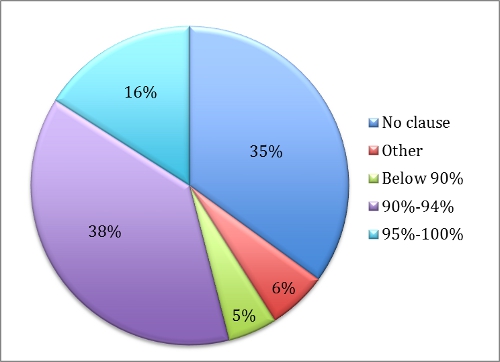

Thankfully, no governor took CCA up on this particular offer. But unfortunately for U.S. taxpayers, and for the very idea of justice, “lockup quotas” are already a very common occurrence in contracts between state and local governments and private prison companies. According to a new study from In the Public Interest (ITPI), a comprehensive resource center on the outsourcing of public services to for-profit corporations, 65 percent of private prison contracts that we studied contain these quotas, illustrated in Figure 1, below.

Figure 1 – Occupancy guarantee provisions in private prison contracts

Outsourcing public services to for-profit corporations is nothing new in American government. Over the past several decades, cash-hungry cities, counties and states have handed over control of countless roads, sanitation departments, water treatment facilities and other services to businesses that promise to run these operations “better, faster and cheaper” than the government.

Sometimes, when done responsibly and with taxpayers’ best interests in mind, outsourcing can work. But too often, deals are struck between corporations and public officials that lack transparency and accountability, and, in the case of private prisons, write a guarantee of corporate profits right into the contract. Perhaps the most egregious recent example of outsourcing gone awry is the 2009 deal to privatize 36,000 Chicago parking meters. Not only did Chicago sell off its parking meters to a Wall Street bank-backed consortium for at least $1 billion too little, but the city is now locked into a 75 year contract that requires taxpayers to reimburse investors whenever the city needs to temporarily close its streets, even for community parades and street festivals.

Such “heads-I-win, tails-you-lose” contracting schemes are bad enough. But they are especially odious when people’s very freedom is at stake. While we do not know whether any American has been placed behind bars to satisfy a contract quota, the existence of such contract language merits asking whether it incentivizes criminal punishment. And they certainly impact other public policy decisions and outcomes.

For example, the state of Colorado originally intended its private prisons for overflow purposes, and the contract with CCA explicitly states that “the state does not guarantee any minimum number of offenders will be assigned to the contractors’ facility.” However, as the state’s crime rate dipped by one-third starting in 2009 and its prisons faced the threat of closure, CCA negotiated the insertion of a quota in the 2013 state budget for all three of its facilities. Instead of using empty bed space at state-run facilities, the Colorado Department of Corrections housed inmates in CCA’s facilities to ensure they met the occupancy requirement. Thanks to the quota, the private prisons were the first priority for placement, rather than the last.

Other states see the effects, too. According to our study, the most frequent quota in private state and local prisons was 90 percent, and three for-profit prison contracts in the state of Arizona operate under contracts that guarantee an astounding 100% occupancy. In effect, if communities realize their objective of a lower crime rate, taxpayers will see no benefit. They will still be on the hook to pay the private prisons as if they remained filled to capacity.

A recent article reported by the Tennessean that followed up on the ITPI study found that taxpayers shelled out nearly $500,000 for empty prison beds in a local women’s prison that had a 90% quota. A spokesperson for CCA, the company that runs the facility, defended the use of quotas to pay for “fixed costs…no matter how many inmates are housed” and that they “enabled us to cover those fixed costs and ensure the State has access to needed capacity, which can fluctuate.” Which sounds reasonable, if you buy into CCA’s premise that incarceration exists to help private prison companies get a return on their investment, rather than to punish and rehabilitate lawbreakers.

The private prison industry also claims that outsourcing ultimately saves taxpayers money. However, numerous studies and audits have shown these claims to be an illusion. For example, a. 2010 report by Arizona’s Office of the Auditor General found that privately-operated prisons housing minimum-security state prisoners actually cost $0.33 per day more than state prisons ($46.81 per diem in state prisons vs. $47.14 in private prisons), while private prisons that house medium-security state prisoners cost $7.76 per day more than state facilities.

The ITPI study encourages lawmakers to review private prison contract quotas and reject them. This recommendation is included in ITPI’s Taxpayer Empowerment Agenda, a comprehensive set of policy proposals to help state and local officials ensure that taxpayers ultimately remain in control of their services.

As former Oklahoma Department of Corrections Director Justin Jones so aptly said, “Just because it’s legal doesn’t make it right for shareholders to make a profit off of the incarceration of our fellow citizens. Humanity deserves better than this.”

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1dpYwVO

_________________________________

Shar Habibi – In the Public Interest

Shar Habibi – In the Public Interest

Shar Habibi is the Research and Policy Director of In the Public Interest (ITPI), a national resource center on privatization and responsible contracting. She previously worked on issues related to state government contracting at a policy and research organization in Texas, where she focused on the privatization of social services.

1 Comments