Earlier this year, the Military Justice Improvement Act was introduced into Congress with the aim of removing sexual assault cases from the chain of command. While some commentators have expressed their concern at the potential for the Act to reduce the authority of military commanders, and thus their effectiveness, others argue that the best way for the military to operate is with a degree of civilian control. Looking at the long history of congressional and executive interference into the military’s internal affairs, Brian Forester, Rachel Sondheimer, and Rachel Yon write that the current debate raises broader questions about the military’s autonomy versus society’s values.

Earlier this year, the Military Justice Improvement Act was introduced into Congress with the aim of removing sexual assault cases from the chain of command. While some commentators have expressed their concern at the potential for the Act to reduce the authority of military commanders, and thus their effectiveness, others argue that the best way for the military to operate is with a degree of civilian control. Looking at the long history of congressional and executive interference into the military’s internal affairs, Brian Forester, Rachel Sondheimer, and Rachel Yon write that the current debate raises broader questions about the military’s autonomy versus society’s values.

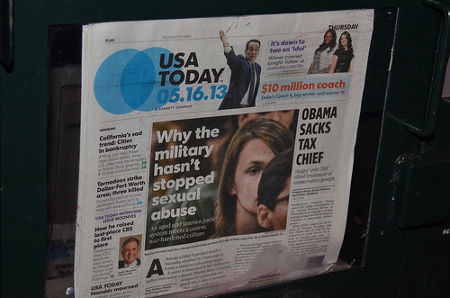

In May, the Department of Defense released an annual report documenting 3,374 reported cases of sexual assault in the previous year (a 6 percent increase from the last report) with just 302 going to trial, and a total of 238 convictions. Another DoD report released in the spring estimated that 26,000 active duty members of the military (more than 6 percent) had “experienced some form of unwanted sexual contact” in the year leading up to the survey. These numbers add to the increasing salience of the problem of sexual assault in the military raised elsewhere by the award-winning documentary The Invisible War and high profile incidents including an Army sergeant, serving as a sexual assault prevention and response coordinator, coming under investigation for abusive sexual contact and assault and a non-commissioned officer at the United States Military Academy filming unsuspecting female cadets in the shower.

The Military Justice Improvement Act (MJIA), offered by Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) as an amendment to the annual military spending bill, is one of a handful of Congressional proposals to alter how the Department of Defense handles claims of sexual assault. Senator Gillibrand’s bill removes sexual assault cases from the chain of command, giving military prosecutors, rather than the accusers’ commanders, the ability to decide whether or not to the try cases. An alternative measure is being offered by Senator Claire McCaskill (D-MO) and is supported by the Department of Defense. This measure would keep court-martial proceedings within the chain of command but would remove commanders’ ability to overturn jury verdicts.

![Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand meets members of the 106th Rescue Wing, Westhampton Beach, NY. By Senior Airman Christopher Muncy [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/files/2013/12/Kirsten-Gillibrand-.jpg)

The UCMJ requires the Commander-in-Chief‘s implementation, which he does via an executive order. He has repeatedly used executive orders to make changes to the UCMJ and the manner in which it is implemented. The UCMJ has also been altered by a number of congressional amendments. The Military Justice Act of 1968 brought the due process rights of members of the armed services closer to those enjoyed by civilians in criminal court. The Military Justice Act of 1983 made procedural changes, including the ability to appeal certain cases from the U.S. Court of Military Appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court. Finally, Congress has recently taken to using the National Defense Authorization Act to amend the UCMJ each fiscal year.

Amendments to the UCMJ have been made in order to increase and improve the due process and procedural rights of defendants in these cases. To date, neither Congress nor the President has fundamentally interfered with the hierarchical structure in which the military deals with these cases or the commanders’ role in the military justice system. As such, while civilians traditionally tinker with the legal process, they rarely, if ever, alter the military’s execution of the system. Given the relative autonomy of military commanders under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the debate over the MJIA highlights broader questions of civilian control of the military. Is congressional intervention in this traditionally militarily autonomous sphere warranted? Should Congress intervene and significantly alter the long-held UCMJ authority of military commanders?

Opponents of the MJIA ground their argument in the assumption that removing military commanders’ authority will harm military effectiveness. The idea that safeguarding the military’s professional autonomy is the best way to both maximize its effectiveness and ensure civilian control is typified in the writings of political scientist Samuel Huntington, whose model of “objective control” provides distinct military and civilian spheres of operation. By Huntington’s account, increased civilian meddling in the military sphere erodes military professionalism, thus reducing its functional effectiveness as an organization. This sentiment is prominently reflected in the views of opponents to the Military Justice Improvement Act, such as former congressman Allen West, who argues that such congressional interference will “break down the good order and discipline of the United States military.” Additionally, MJIA critic Mackubin Thomas Owens links the proposed legislation to a broader “feminist assault” on the culture of the U.S. military, which would diminish its effectiveness. Owens’ argument implies that military culture is necessarily more masculine than mainstream American society, and that its alteration would undermine military effectiveness.

While Huntington’s ideal conception of civil-military relations encourages the separation of the military from the civilian sphere, the opposing construct – articulated by sociologist Morris Janowitz – argues that civilian penetration of military culture is the best way to maintain control. Believing that the sexual assault problem is due to pernicious aspects of a masculine military culture, MJIA advocates reject the notion that military commanders alone can effectively address problems of sexual assault, suggesting that military commanders’ autonomy actually breeds a conflict of interest. The Center for American Progress reports that “since military commanders are evaluated on their command climate and are rated poorly if sexual assault takes place within their unit, it is not in a commander’s best interest to even investigate allegations.” Therefore, according to MJIA advocates, civilian leaders in Congress have a responsibility to intervene and alter the procedures administering such cases.

Huntington and Janowitz’ approaches offer significant theoretical leverage toward understanding the debate over the MJIA and other similar efforts. Moreover, the MJIA is one among several other contemporary issues with similar civil-military implications, such as the repeal of “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” and the integration of women into combat roles. Further analysis of these issues through the civil-military framework provides fresh insight as the U.S. considers how to balance military effectiveness with the need for its military to represent the values of the society it serves.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics, the United States Military Academy, the United States Army, or the Department of Defense

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/18bkJYN

_________________________________

Rachel Sondheimer – United States Military Academy

Rachel Sondheimer – United States Military Academy

Rachel Sondheimer is an associate professor and the director of the American Politics, Policy and Strategy program in the Department of Social Sciences at the United States Military Academy. She holds a BA in Government from Dartmouth and PhD in Political Science from Yale. Her current research focuses on civil-military relations and military and overseas voting regulations.

Brian Forester – United States Military Academy

Brian Forester – United States Military Academy

Brian Forester is an Army Major and instructor in the Department of Social Sciences at the U.S. Military Academy (USMA). He is a graduate of USMA and holds an M.A. in Political Science from Duke University. He has multiple overseas deployments, and his research interests include civil-military relations, public opinion, and quantitative methodology.

Rachel Yon – University of Florida

Rachel Yon – University of Florida

Rachel Yon is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Florida in the Department of Political Science. Her concentrations are Public Policy, American Government, and Methodology with a focus on public policymaking and the juvenile justice system. Her most recent appointment is as an Instructor in the Department of Social Sciences and Executive Officer of the Combating Terrorism Center at USMA.