The Great Recession, coupled with concerns over the growing budget deficit, resulted in a renewed debate about the social safety net. While support for welfare benefits usually splits along partisan lines, Yotam Margalit examines how personal experiences of hardship during the financial crisis affected attitudes towards social spending. While he finds that first-hand experience of a job loss does lead to a convergence in the welfare preferences of left and right-leaning voters, the data suggest that the changes in the welfare attitudes of the job losers are fairly short-lived, dissipating soon after they find new employment. Overall, the first four years of the Great Recession are found to have brought about a drop in the public’s support for welfare spending.

The Great Recession, coupled with concerns over the growing budget deficit, resulted in a renewed debate about the social safety net. While support for welfare benefits usually splits along partisan lines, Yotam Margalit examines how personal experiences of hardship during the financial crisis affected attitudes towards social spending. While he finds that first-hand experience of a job loss does lead to a convergence in the welfare preferences of left and right-leaning voters, the data suggest that the changes in the welfare attitudes of the job losers are fairly short-lived, dissipating soon after they find new employment. Overall, the first four years of the Great Recession are found to have brought about a drop in the public’s support for welfare spending.

The financial crisis of 2008 has had a harrowing impact on the well-being of citizens worldwide. Job dislocations, long spells of unemployment, drops in income, and deep economic uncertainty are only some of the hardships that afflicted millions of families since the beginning of the Great Recession. While governments struggle with growing claims on social protection programs as well as ever-widening budget deficits, the debate about the proper role of government and the desired level of welfare spending has been brought to the fore. What is the overall impact of the financial crisis on the electorate’s attitudes toward social spending? Did the personal experience of hardships affect voters’ support for increased welfare assistance and, if so, how did right-wing voters reconcile their pre-crisis attitudes of opposition to welfare spending with their changing circumstances?

To put this last point in starker terms, consider a hypothetical case of two otherwise similar individuals, one positioned ideologically on the left and the other on the right, who lose their jobs at the same time. Would the same personal predicament lead to a convergence in their policy preferences, whereby the right-leaning individual would become significantly more supportive of welfare assistance, or would their different ideological dispositions yield two distinct responses, in line with their previously held views?

An impressive array of research explored related questions, yet clear-cut answers have been scant for two main reasons: first, the findings themselves are ambiguous. Whereas some analyses find strong correlations between voters’ views on social policy and their economic standing, other studies that examine different survey data find no clear evidence linking people’s personal economic circumstances to their views on the specific policies from which they benefit . Second, previous analyses relied almost exclusively on single-shot cross-sectional data, a limitation that keeps the causal link between economic standing and policy preferences unclear. While a person’s employment situation could shape her attitudes toward welfare policy, unobservable characteristics such as parental influence or the upbringing environment could plausibly account both for her preferences on welfare provision and her position in the labor market.

In a recent study, I set out to explore the questions posed above and address some empirical limitations of previous work on the topic. Using an original panel study that I helped administer, which consisted of four waves of surveys tracking the same national sample of American respondents (between July 2007 and March 2011), I investigate the relationship between changing economic circumstances and individuals’ preferences on welfare policy. I focus on three types of economic shocks: a substantial drop in household income, a subjective decrease in perceived employment security, and the actual loss of a job. The study takes advantage of the fact that in these repeat interviews detailed information was collected not only on respondents’ changing labor market circumstances but also on their political attitudes.

The study provides several notable findings: The data show very clearly that, among voters of all partisan persuasions, the first four years of the Great Recession have brought about a drop in overall support for expanded welfare spending among the general population. As Figure 1 shows, support for government assistance to the needy and the unemployed fell among Democrats, Independents, and, in relative terms, most sharply among Republicans. This pattern is consistent with the notion that the public was more concerned about growing budget deficits and expectations of higher future taxes than about building a tighter safety net for those in need.

Figure 1: Support for Government Assistance from July 2007 to March 2011

Yet the shift in the general public does not mean that economic hardships brought about by the crisis had had no impact on citizens’ preferences; on the contrary. I find strong evidence of bifurcated citizenry: those personally affected by the shocks, primarily by the loss of a job, became significantly more supportive of expanded welfare spending, while those relatively unaffected by the hardships became, on average, less supportive of such spending. The magnitude of the effects was substantial: holding all else constant, the loss of a job was associated with an increase in the average probability of support for greater welfare spending by 22-25 percentage points (the effect of a drop in income was substantially smaller). These results are robust to a broad range of empirical specifications and placebo tests (for example, attitudes of those personally affected by job loss changed substantially with respect to welfare policy but not with respect to largely unrelated policy domains such as global warming or cultural values).

Yet the shift in the general public does not mean that economic hardships brought about by the crisis had had no impact on citizens’ preferences; on the contrary. I find strong evidence of bifurcated citizenry: those personally affected by the shocks, primarily by the loss of a job, became significantly more supportive of expanded welfare spending, while those relatively unaffected by the hardships became, on average, less supportive of such spending. The magnitude of the effects was substantial: holding all else constant, the loss of a job was associated with an increase in the average probability of support for greater welfare spending by 22-25 percentage points (the effect of a drop in income was substantially smaller). These results are robust to a broad range of empirical specifications and placebo tests (for example, attitudes of those personally affected by job loss changed substantially with respect to welfare policy but not with respect to largely unrelated policy domains such as global warming or cultural values).

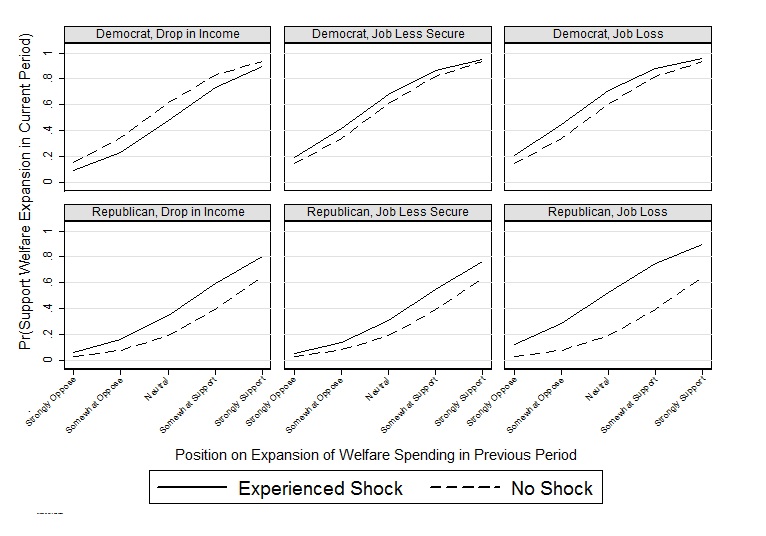

As for the hypothetical case of the two laid-off individuals, I find that the personal experience of a job loss did indeed lead to a convergence in the welfare preferences of left and right-leaning voters. In particular, I find that laid-off Republicans and Independents grew significantly more supportive of welfare assistance, while among Democrats the effect was much smaller. Figure 2 highlights this difference, presenting the probability of a pro-welfare shift as a function of respondents’ initial partisan affiliation and whether they experienced the shock.

Figure 2: Positions on expansion of welfare

(Note: The graphs report the probability of support for welfare expansion (on the Y-axis) as a function of the individual’s level of support for the policy in the previous period (measured on the X-axis along a five-point scale). Each graph corresponds to a different type of economic shock. Results are reported separately for Democrats and Republicans.)

The main pattern that the graph illustrates is that the welfare preferences of Republicans harmed by the shocks, particularly the loss of a job, diverged sharply from the preferences of their unaffected Republican counterparts; among Democrats, those who experienced a shock continued to hold similar preferences to those who did not. The analysis indicates that this finding is not fully accounted for by a “ceiling effect” (i.e. all Democrats already supporting welfare expansion), but the data cannot definitively tell us what explains the remaining variation. My best speculation is that partisans who are willing to explicitly depart from a widely shared party stance on a central issue are likely to: (i) hold stronger-than-average views about that issue, and (ii) support the party due to its position on some other important dimension or due to a longstanding emotional connection with the party. Thus, Democrats that were initially opposed to welfare expansion may represent a hard “core” whose views on this issue are less malleable. This may account for the small observed shift in their views on welfare policy following a worsening in their personal circumstances.

Finally, I find that with the passing of time, as job losers regain employment, their support for the expansion of welfare spending decreases significantly. This shift in attitudes among the re-employed is more frequent among voters on the right. Taken together, the findings suggest that while economic shocks can have a sizable effect on welfare preferences of individuals, this effect is probably not a reflection of a profound conversion in their political worldview. Rather, it seems that the attitudinal change reflects a more provisional response to an immediate and sometimes temporary need. Such changes in preferences for welfare spending can therefore be fairly short-lived.

To what extent do these findings generalize to other countries? Brian Burgoon (University of Amsterdam) and I are now exploring this question, using all suitable panel data produced in any advanced economy. Whether we find, for example, that the attitudes of citizens in corporatist economies respond differently to sudden hardships than workers in an American-like liberal economy is an open question. One recent working paper by Linna Marten suggests that that might not be the case. Examining panel data from the Swedish National Election Study, she reports very similar findings: loss of a job is associated with a sizable increase in support for social insurance, the newly re-employed exhibit similar attitudes to those who never lost a job, and income drop has only a marginal impact on citizens’ preferences. It may be the case, then, that national welfare regimes have less of a mediating impact than the conjecture above suggests. New research will hopefully provide further insight into this question

This article is based on the paper, “Explaining social policy preferences: Evidence from the Great Recession” which appeared in the February 2013 edition of the American Political Science Review. A version of this post has also appeared in the Comparative Politics Newsletter, Fall 2013.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: bit.ly/J6E6XZ

_________________________________

Yotam Margalit – Columbia University

Yotam Margalit – Columbia University

Yotam Margalit is an assistant professor at Columbia University specializing in the fields of international and comparative political economy. Much of his current work deals with the political consequences of globalization, examining how its effects influence electoral politics and shape mass preferences on issues such as welfare spending, trade, and immigration.