A number of U.S. states currently impose some form of legislative term limits in order to ensure competition and accountability among elected officials. However, some argue that term limits actually make legislators less responsible to their constituents, causing them to abstain from more votes and shirk their duties. Jennifer Hayes Clark and R. Lucas Williams argue that the willingness to shirk depends more on future career goals and the type of vote rather than term limits alone.

A number of U.S. states currently impose some form of legislative term limits in order to ensure competition and accountability among elected officials. However, some argue that term limits actually make legislators less responsible to their constituents, causing them to abstain from more votes and shirk their duties. Jennifer Hayes Clark and R. Lucas Williams argue that the willingness to shirk depends more on future career goals and the type of vote rather than term limits alone.

In 1990, citizen initiatives established term limits on legislative service in California, Colorado, and Oklahoma. Since this initial adoption, eighteen other states subsequently have adopted some form of legislative term limits; however, the state supreme courts overturned these initiatives in four states and the legislatures repealed them in another two states. That leaves fifteen states that currently limit the service of their legislators in some form. Proponents of legislative term limits in the U.S. argue that these reforms are necessary to ensuring competition in elections, limiting the “incumbency advantage,” and ensuring accountability among elected officials. Opponents argue that term limits threaten the connection between legislators and voters, leading legislators to shirk their responsibilities to constituents.

Academic research focuses on two different types of shirking that may occur when legislators are no longer accountable to voters: ideological shirking in which a member’s voting record noticeably shifts once the member is no longer constrained by voters and participatory shirking in which a member is more likely to abstain from floor votes once he or she is unconstrained by voters. These previous studies have produced mixed results concerning whether legislators shirk once they are unconstrained by voters. While some studies find significant levels of ideological and participatory shirking among retiring U.S. House members during their last term in office, other research examining the effects of term limits on shirking has shown remarkable consistency in legislative behavior despite severing the electoral connection between legislators and constituents.

Our current research investigates the effect of term limits on ideological and participatory shirking among state legislators. We argue that legislators’ willingness to shirk depends primarily on their future career goals rather than whether the member is currently affected by term limits. Members who face term limits yet have ambitions to pursue another public office (local, state or federal) have incentives to avoid shirking their duties while in office. We predict that there will be less ideological change in their voting behavior, and they will also be less likely to abstain from floor votes.

We also argue that ideological and participatory shirking will vary according to the type of vote under consideration. Since party leaders hold resources that legislators want (party leadership powers vary, but key committee appointments and agenda setting abilities are two examples of institutional powers), members are beholden to party leaders in their chamber. Parties tend to exert their influence on procedural votes—which include motions to end debate, recommit, table, and instruct conferees— more so than on final passage votes, where party leaders may excuse defections from members if the vote could make the member vulnerable in the next election (see Cox and McCubbins). Under these conditions, legislators who are constrained by term limits but seeking another political office have incentives to avoid shirking, especially on procedural votes which are vital to party leaders maintaining control over the floor.

Using data consisting of individual member careerism decisions (whether members ran for another office or retired from politics), candidate-specific variables (including party affiliation, race, gender, and leadership status), and district-related variables (including constituency ideology and competitiveness), our analysis shows that legislative shirking is dependent upon members’ career goals and the type of vote. Legislators face far fewer constrains on final passage votes, and therefore there is no significant ideological shift in the voting patterns of legislators pursuing another office and those leaving public office. However, on procedural votes, members who were affected by term limits yet pursuing another public office showed a remarkable level of ideological consistency. We believe that their consistency on procedural votes is due to pressure exerted by party leaders over procedural matters.

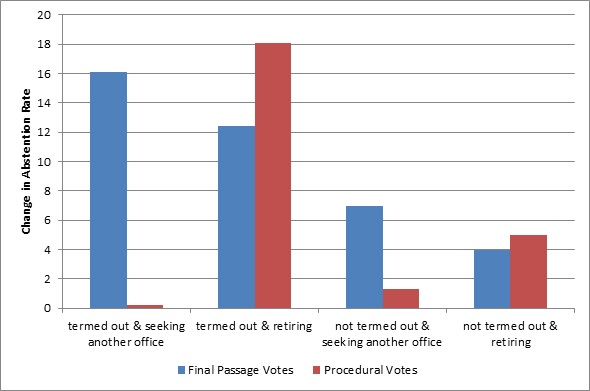

In analyzing changes in members’ participation rates on final passage votes, members who are termed-out and not seeking another public office experienced significantly higher rates of abstention. The changes in abstention rates by electoral circumstance and type of floor votes are presented in Figure 1. Members who are termed out and not pursuing another public office saw about a 12% increase in their abstention rates on final passage votes, while those members who have voluntarily left the chamber only experienced about a 4% increase in their abstention rates. Members who are termed out yet pursuing another office had an increase of about 16%, and an abstention rate increase of about 7% for those not termed out but seeking another office.

Figure 1: Participatory Shirking by State Legislators

Procedural votes showed a different pattern. Members facing term limits yet pursuing another public office did not increase their abstention rates. However, those who were retiring did show a substantial increase in their abstention rates on procedural votes (about 18% for termed-out legislators and 5% for those not termed-out). Legislators who were not constrained by term limits but were pursuing another office experienced about a 1% increase in their abstention rates on procedural votes.

Procedural votes showed a different pattern. Members facing term limits yet pursuing another public office did not increase their abstention rates. However, those who were retiring did show a substantial increase in their abstention rates on procedural votes (about 18% for termed-out legislators and 5% for those not termed-out). Legislators who were not constrained by term limits but were pursuing another office experienced about a 1% increase in their abstention rates on procedural votes.

Our research has broader implications for those interested in representation and the role of parties in legislative politics. Our analyses suggest that constituents select legislators who are ideologically similar to themselves and thus representatives do not shirk ideologically across all types of votes, even when the electoral connection is eliminated. Also, the presence of term limits reduces the rate of legislative participation in voting, but this varies by the nature of the vote under consideration (with final passage votes influenced much more). This raises other potential questions concerning popular control of democratic institutions. If the act of severing legislators connection from voters produces shirking at one of the more visible stages of the legislative process (voting on policy matters), then are representatives also similarly disengaging at other stages of the policymaking process?

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: bit.ly/1hifAyD

_________________________________

Jennifer Hayes Clark – University of Houston

Jennifer Hayes Clark – University of Houston

Jennifer Hayes Clark is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and a Research Associate at the Center for Public Policy at the University of Houston. Her primary areas of research interest include American political institutions, public policy, and quantitative research methodology.

_

R. Lucas Williams – University of Houston

R. Lucas Williams – University of Houston

Lucas Williams is a graduate student at the University of Houston. His interests include both institutional and behavioral approaches to the study of Congress and the state legislatures.