While debt has been an acceptable component of economic life for many decades, the bubble of the early 2000s and the subsequent financial crash took debt burdens to entirely new levels. Johnna Montgomerie argues that the contemporary model that social protection will come from asset-based welfare and easy credit has led to massive financial insecurity, especially for the young and old, who have found rising debts to have far outpaced their incomes. Already high debt levels for young people and senior citizens mean that any falls in income through unemployment or rising healthcare costs will leave them to face debt repayments of 25 to 49 percent of their income.

While debt has been an acceptable component of economic life for many decades, the bubble of the early 2000s and the subsequent financial crash took debt burdens to entirely new levels. Johnna Montgomerie argues that the contemporary model that social protection will come from asset-based welfare and easy credit has led to massive financial insecurity, especially for the young and old, who have found rising debts to have far outpaced their incomes. Already high debt levels for young people and senior citizens mean that any falls in income through unemployment or rising healthcare costs will leave them to face debt repayments of 25 to 49 percent of their income.

Last December, in a speech which many consider to be a spiritual successor to Lyndon Johnson’s ‘War on Poverty’ fifty years earlier, President Obama took on the current debate over inequality. In his address, he also turned to Americans’ rising debts:

“We took on more debt financed by a juiced-up housing market. But when the music stopped, and the crisis hit, millions of families were stripped of whatever cushion they had left…When families have less to spend, that means businesses have fewer customers, and households rack up greater mortgage and credit card debt”

But what led to the rise of America’s ‘debt-safety net’ in the lead up to the financial crisis? This surge in debt is the basis for my alternative account of the US liberal welfare regime during the 2001-2007 boom years, which put debt-led consumption at its core. By investigating the financial insecurity of young adults and senior citizens, I find that in the wake of the crash, there has been a failure of asset-based welfare and an inability of households to move beyond their historical dependence on earned income making indebtedness essential to household social participation and protection.

Young adults and senior citizens are important because they have a unique relationship to the liberal welfare regime – they are among the last remaining social groups that are usually deemed politically worthy of state support. Their links to specific forms of state support such as pensions, healthcare and education provide a basis for considering the outcomes of changes in the liberal welfare regime. Through direct income transfers to the retired or unemployed and the funding of higher education and skills training, liberal welfare capitalism serves as a vital buttress to economic growth and stability.

Borrowing is now way of life for the young

High debt levels in the early stages of working life are often accepted uncritically as a necessity to begin building assets and long-term wealth holdings. Growth in overall debt levels since 2001, especially compared to income levels, suggests that indebtedness is threatening – not aiding – long-term financial security. Part of the problem is contextualizing young people’s borrowing over their lifetime, where debt is seen as necessary and temporary for expected wealth gain later in life. Many see indebtedness as a necessary ‘risk’, but the sheer volume of debt now required for social participation surely undermines this common assumption.

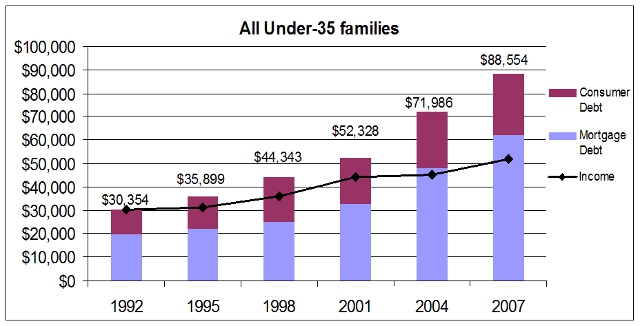

Figure 1 below illustrates the average total debt and income levels of all under-35 households, showing the deleterious impact of the 2001–2007 bubble on financial stability. Throughout the 1990s, total debt closely tracked income at 100.1 percent of income in 1992 and 122 percent in 1998. Over the decade, total outstanding debt increased by approximately $14,000 and income by $5,800; by contrast, in the 2000s debts increased just over $44,000 compared to a $7,500 increase in annual pre-tax income reaching 171 percent of income in 2007. Young adults already face unique financial insecurity because they comprise the bulk of temporary or contract workers, making them vulnerable to job loss. Rising indebtedness compounds these problems, because under-35s are less able to cope with relatively minor drops in income. A 10 percent drop in 2007 pre-tax income levels, for example resulting from a pay cut or reduction in non-wage benefits, increases the debt repayment burden from 20 to 22 percent of household income. A more substantial 25 percent drop, approximating a job loss or temporary lay-off for less than three months, would increase the repayment burden to 26 percent of income.

Figure 1 – Young adults’ average outstanding debts and income

Source: Survey of Consumer Finances, All families with head under 35, n=4010(1992); 4429 (1995), 4149 (1998), 4030 (2001), 3769 (2004), 3510 (2007).

Senior citizens: house rich and cash poor

Individuals who retire from the workforce are expected to deplete their savings and wealth holdings; however, approximately 84 percent of over-65 households receive social security benefits and 40 percent claim social security as their largest income source—suggesting direct income transfer are substantially more important to senior citizens than their stock asset holdings. Importantly social security is one of the largest expenditures in the US federal budget, faced with an aging population and a declining birth rate, successive US administrations attempt to ‘plug the fiscal gap’ by targeting this entitlement program for cuts or privatization. Therefore, rising indebtedness amongst the elderly population links directly to welfare reform.

The over-65 households are a diverse group: some are very wealthy but most survive on meagre incomes; some retire before 65 and others continue working and earning from choice or necessity. Most over-65s are ‘house rich and cash poor’, greater access to equity withdrawal is seen as an efficient way of smoothing life-cycle consumption and allocating scarce household resources. Indeed, this is a key tenet of asset-based welfare initiatives.

Rather than follow convention and create subpopulations of households that receive social security or a social security income supplement (SSI) versus those with private pensions and/or property and investment income, I compared all over-65 families to those with mortgage holdings and to the numerical majority of over-65 households earning below $40,000 a year (in the Survey of Consumer Finances a third of over-65s earn below $20,000 and a further 25–30 percent (depending on the year) earn between $20,000–39,999). This highlights the key failing of asset-based welfare: inadequate social protection because rising indebtedness creates financial insecurity.

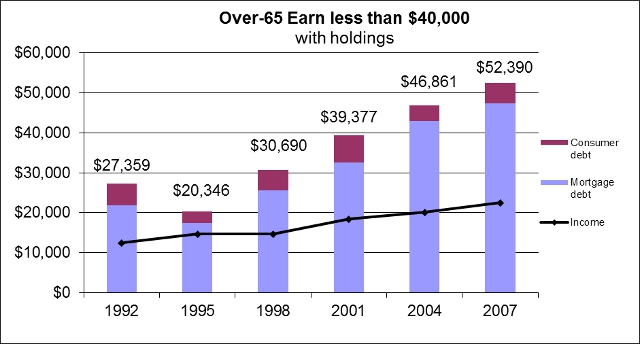

Figure 2: Senior Citizens’ average income and outstanding debts for households that own home and earning less than $40,000

Source: Survey of Consumer Finances, selected households with head over-65, with mortgage holdings and earning less than $40,000 (Bulletin Categories 1 and 2), n=171 (1992), 194 (1995), 213 (1998), 236 (2001), 316 (2004), 333 (2007)

Throughout the 1990s, average debt increased by $3,300 and income by $2,200; by comparison, over the following decade debt increased $13,000 against a meagre $4,000 growth in average income, reaching 232 percent of income in 2007. Like other groups, lower-income seniors experienced a steady reduction in debt repayment obligation as a proportion of income, from 56 percent in 1992 to 36 percent in 2007, largely because of lower interest rates. Nevertheless, the cost of servicing a much larger debt still created additional claims against largely fixed incomes, with a 10 percent or 25 percent drop in income raising repayments to 40.5 or 49 percent of average annual pre-tax income, respectively. Senior citizens living on modest incomes borrow heavily for daily living because incomes have not kept pace with the rising living costs unique to over-65s: rising healthcare costs and gaps in Medicare coverage, cuts to ‘legacy costs’ mean reduction in former employer’s benefits pay-outs combined with low-interest rates that erode savings pots.

Debt as Panacea

America’s debt safety-net is the product of decades of sustained reforms to the liberal welfare regime. Combined with the 2001–2007 credit and asset bubble, it has created a household sector now plagued by financial insecurity. Many households borrowed heavily to acquire assets but also to cope with the multiple demands of daily life: buying a home, purchasing an automobile, getting a university degree and buying ‘big-ticket’ as well as for everyday expenses. An uncomfortable reality is emerging in the United States in which the cost of social participation is beyond the income of most households.

The contemporary welfare paradigm (wrongly) assumed that adequate social protection would naturally result from asset-based welfare and using easy credit, rather than rising wages and salaries, to maintain living standards. After 2001 many over-65 households were still reliant on social security, but were also borrowing against existing equity in their home, or more problematically, against the inflated value of their home. Young adults became indebted by borrowing for social participation: to buy homes, get an education, supplement lacking employer-sponsored benefits such as medical costs and create a stopgap during unemployment. The evidence indicates that the recent credit bubble has made young adults and senior citizens more financially insecure.

These findings help to provide a picture of why economic recovery is failing. The 2007 financial crisis exposed the politics of abandonment that has shaped the liberal welfare regime over the past two decades: the old and the young are left to cope with the long period of economic restructuring as well as protracted asset and credit bubble through unsustainable borrowing. Yet, how households are meant to cope with a financial crisis, prolonged recession and faltering recovery without going further into debt is by no means clear.

This article is based on the paper “America’s Debt Safety Net” in the December 2013 issue of Public Administration.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1gFaDPU

_________________________

Johnna Montgomerie – Goldsmiths, University of London

Johnna Montgomerie – Goldsmiths, University of London

Johnna Montgomerie is a Lecturer in Economics at the Department of Politics at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research interests are in all forms of household debt (mortgage, student loans, consumer credit, payday lending) and its relationship to Anglo-American financialisation, especially in the context of never-ending crisis and the new Age of Austerity. She is also interested in exploring innovative methods for exploring the political economy of everyday life.