While racial attitudes have made enormous progress in the 50 years since the Civil Rights Act became law, racism and inequality are still powerful forces in our society. However, these negative feelings now tend to take shape in hidden, persistent resentment, rather than overt racism. In their recent research, Christopher Weber, Howard Lavine, Leonie Huddy, and Christopher Federico, find a positive relationship between whites living in high-diversity areas and negative racial stereotypes. They also show the difficulty in measuring these effects on those who are skilled at altering their behavior to comply with societal norms.

While racial attitudes have made enormous progress in the 50 years since the Civil Rights Act became law, racism and inequality are still powerful forces in our society. However, these negative feelings now tend to take shape in hidden, persistent resentment, rather than overt racism. In their recent research, Christopher Weber, Howard Lavine, Leonie Huddy, and Christopher Federico, find a positive relationship between whites living in high-diversity areas and negative racial stereotypes. They also show the difficulty in measuring these effects on those who are skilled at altering their behavior to comply with societal norms.

Since the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act, the nature of racism has changed markedly in the United States. In an era marked by greater racial tolerance, old-fashioned racism has declined. When we measure racial attitudes in explicit terms—such as the expressed belief that blacks are biologically inferior to whites—empirical evidence shows that racism has decreased. Yet, on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, a host of objective indicators demonstrate persistent racial inequality. Across economic, educational, criminal sentencing, incarceration rates, health, social, and political dimensions, blacks continue to lag behind whites. Nearly fifty-percent of the U.S. population, according to a 2013 Pew Report, feels that racial equality has not been fully realized. Yet, many white Americans remain opposed to policy designed to reduce inequality—policies like quotas in hiring, promotion, and college admissions.

Scholars remain at odds over the origins of opposition to race targeted policies. On one hand, policy opposition may originate from race-neutral factors, which, in the current climate of greater racial tolerance, overshadow race-motivated opposition. According to this perspective, core values, such as individualism, belief in a limited government, and egalitarianism, shape opposition to policies designed to benefit a subset of society.

On the other hand, a separate line of empirical work has shown that tolerant racial norms have not erased racial negativity, but rather, racial animus has adapted to these norms. Racism is now subtle, or more implicit; it is not driven by explicit beliefs about biological differences between whites and blacks, but rather, it is a function of persistent resentment.

In our recent research, we engage these competing literatures by arguing that particular racial contexts alter the link between racial negativity and policy attitudes among white individuals. In particular, racial diversity should magnify the relationship between prejudice and policy. Specifically, the link between negative racial stereotypes (e.g., endorsing the item “blacks don’t work as hard as whites”) and opposition to race-targeted policy should be greatest in neighborhoods with high racial diversity. In contexts where whites live among fewer blacks, we expected a weaker link between stereotypes and policy opposition.

We also expected this effect to be more difficult to detect among a subset of the public. White respondents who are more responsive to social norms and live in diverse areas characterized by a climate of tolerance should show a weakened relationship between negative racial stereotypes and policy. This occurs, in part, because they are less likely to openly express racial negativity, adding an additional wrinkle to understanding the political consequences of racial diversity: Overall, whites living in a diverse area will increase the political importance of negative racial attitudes, but this effect will be more difficult to detect among those most sensitive to their social context.

To identify these individuals, we rely on a construct developed in psychology, the self-monitoring scale. Self-monitoring is a motivational characteristic referring to the extent by which individuals engage in impression management and alter their behavior according to pervasive norms. In our work, we employed a four-item self-monitoring scale, which included agree/disagree questions such as “In order to get along and be liked, I tend to be what people expect me to be rather than anything else” and “I may deceive people by being friendly when I really dislike them.”

To test our expectations regarding the complex relationship between racial stereotypes and policy preferences, we relied on a survey administered to a representative sample of white New York State residents. Given that we knew the participant’s location, we paired the survey data with U.S. Census data, allowing us to generate an estimate of the percentage of blacks within each respondent’s zip code. Within the survey itself, participants answered a battery of questions about racial policy (e.g., opposition to housing integration, aid to blacks), as well as several questions about the death penalty. We measured negative stereotypes with two items: (1) The extent to which the respondent believes blacks are lazy (versus hardworking), and (2) the belief that blacks are violent (versus not very violent). In our statistical models, we also “controlled” for a host of factors relating to racial policy attitudes.

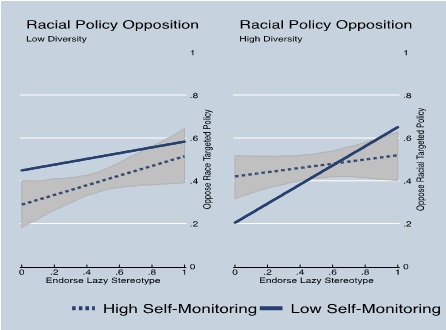

In our analyses, we found consistent support for our key expectations. The relationship between negative stereotype endorsement and opposition to race targeted policies was magnified in high diversity contexts. However, this effect was strongest for low self-monitors. It was more difficult to measure negative racial stereotypes among high self-monitors—those susceptible to tolerant racial norms—and as a consequence it was more difficult to detect the link between racial stereotypes and racial policy views.

Due to the complexity of these relationships, we generated a graphical depiction of these results, shown in Figure 1. The two columns correspond with two scenarios: The panel on the left represents simulated opposition to race-targeted policy in low racial diversity contexts; the panel on the right represents predicated opposition to race-targeted policy in high diversity contexts. In each panel, we generated predictions across levels of stereotype endorsement among low self-monitors (the solid line) and high self-monitors (the dotted line). The gray area represents statistical uncertainty.

Figure 1: The Relationship between Stereotypes and Racial Policy across Self-Monitoring and Racial Diversity (White Respondents)

What is particularly noteworthy is that the slope of the line is relatively flat for high self monitors and the line doesn’t change across levels of diversity. This indicates the consequences of negative stereotype endorsement may be more difficult to detect among high self-monitors.

What is particularly noteworthy is that the slope of the line is relatively flat for high self monitors and the line doesn’t change across levels of diversity. This indicates the consequences of negative stereotype endorsement may be more difficult to detect among high self-monitors.

A different pattern emerges for low-self monitors: The difference in policy opposition between those who reject and those who endorse the stereotype is magnified in situations of greater racial diversity.

We believe these findings have implications for our understanding of racial attitudes. The expression of negative racial attitudes has not disappeared, but rather, racial animus is largely context dependent and conditional on an individual’s susceptibility to tolerant social norms. We encourage scholars and practitioners alike to fully consider this complexity when attempting to understand the deep divisions that continue to define racial policy attitudes in contemporary politics.

This article is based on the paper “Placing Racial Stereotypes in Context: Social Desirability and the Politics of Racial Hostility,” which appeared in the American Journal of Political Science.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1fVdYuI

_________________________________

Christopher Weber – University of Arizona

Christopher Weber – University of Arizona

Chris Weber is an Assistant Professor in the School of Government and Public Policy and the University of Arizona. His research centers on political psychology and political behavior, with a focus on American political campaigns and ideology.

Howard Lavine – University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Howard Lavine – University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Howard Lavine is the Arleen Carlson Professor of Political Science and Psychology at the University of Minnesota. His recent book, The Ambivalent Partisan: How Critical Loyalty Promotes Democracy, has won the Robert E. Lane Book Award and the David O. Sears Book Award.

Leonie Huddy – Stony Brook University

Leonie Huddy – Stony Brook University

Leonie Huddy is a Professor of Political Science and Stony Brook University. Her research interests include political attitudes, groups and politics, socio-political gerontology, women and politics, and survey methodology.

Christopher Federico – University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Christopher Federico – University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Christopher Federico is an Associate Professor of Psychology and Political Science at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. His research interests focus on the organization of whites’ racial attitudes and the informational and motivational antecedents of attitude and belief-system structure.