While many hoped that this would be the year Congress would pass much needed immigration reform, John Boehner recently announced that he does not see a way forward on the issue. With federal government gridlocked, some states and counties have taken immigration enforcement upon themselves. Genti Kostandini and Elton Mykerezi examine the effects of local action on the agricultural industry, concluding that there is reduced immigrant presence in counties that have enforced immigration laws, leading to a decline in hired labor share, increased expenses per worker, a lower number of workers, and an overall drop in earnings for the affected farms.

While many hoped that this would be the year Congress would pass much needed immigration reform, John Boehner recently announced that he does not see a way forward on the issue. With federal government gridlocked, some states and counties have taken immigration enforcement upon themselves. Genti Kostandini and Elton Mykerezi examine the effects of local action on the agricultural industry, concluding that there is reduced immigrant presence in counties that have enforced immigration laws, leading to a decline in hired labor share, increased expenses per worker, a lower number of workers, and an overall drop in earnings for the affected farms.

Immigration legislation in the U.S. has been subject to considerable debate; while most believe that an overhaul is necessary, there is little change happening at the federal level. This is likely due to varied preferences on the content of such reform. These diverse opinions have been displayed in an unprecedented surge of legislation at the state and even the county level.

The last major piece of legislation at the federal level was the passage of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986, which legalized 3 million illegal workers and put new regulations in place to prevent the hiring of undocumented workers. Immigration policy is a federal matter, but lack of major reform since 1986, created a political vacuum that states and counties responded to by taking charge on this issue. Legally, section 287(g) of the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IRRA) opened the door to local enforcement. This section allows state and county law enforcement agencies to enter into agreements with Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE) to train their officers and expand their authority to perform certain immigration enforcement duties.

Section 287(g) lay dormant from 1996 until 2001. During the period 2002-2011, 10 states and 49 counties adopted 287(g) programs and more than 180,000 illegal immigrants were detained for removal by local police under authority afforded by section 287(g). These apprehensions have been followed by demonstrations and protests in multiple jurisdictions.

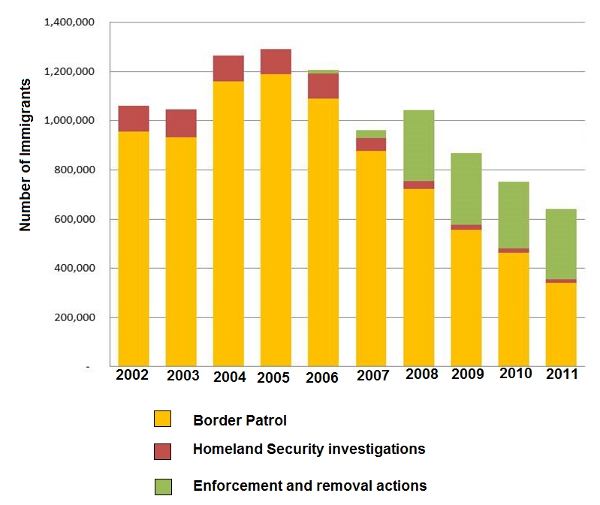

Figure 1 illustrates the apprehension of undocumented individuals in the U.S. by federal border patrols, homeland security investigations or enforcement and removal actions at the state or county level for the period 2002-2011. The share of enforcements and removal actions from states and counties has been intensified, especially in the recent years.

Figure 1: Apprehension of Undocumented Individuals

Source: Office of Immigration Statistics, 2012.

The immigration reforms and the intensified enforcement efforts have attracted the attention of researchers, especially during the last few years. However, studies have focused either on isolated states or counties, on the propensity of noncitizens and foreign-born citizens to move out of these jurisdictions, and on their impacts on certain sectors. Interestingly, implications of these reforms in the agriculture sector may have been overlooked. Given that more than 50 percent of the U.S. agriculture workforce is comprised of illegal immigrants and that agriculture is a major industry in the U.S., it is essential to analyze the effects of these laws and their implications for the farming sector.

When 287(g) programs are implemented new immigrants may not move to the adopting counties and current immigrants may move to non-program counties due to their fear of being caught and deported. Using nationally representative data on millions of persons from the American Community Survey, we find that the share of non-citizens and foreign-born individuals in counties that are three years into the 287(g) program is 13 percent lower than that of citizens and foreign-born individuals during the pre-program period while adjacent counties and other non-program counties did not experience such a decline.

After establishing, that there are disproportionate changes in the composition of the labor force, we turn our attention into the county level farm outcomes that may be affected by potential labor shortages as a result of 287(g) programs. We find evidence that farms in adopting counties have experienced a decline in hired labor share, an increase in expenses per hired worker, and lower numbers of workers per acre compared to those during the pre-adoption period and compared to those in similar non-program counties. Additionally, we find that farms in counties with 287(g) programs have also experienced a relative decrease in their earnings. These quantitative findings provide support for numerous reports on specific U.S. areas from newspapers and magazines on farmers losing millions of dollars due to unharvested products on the fields because of potential ‘labor shortages.’

Recently, U.S. immigration policy has seen stricter immigration laws in some states and also efforts to legalize more than 11 million illegal immigrants that currently reside in the U.S. In addition, there are indications that undocumented workers will be scarcer in the U.S. during the coming years. These changes may have significant impacts not only on the agricultural sector but also on other low-skilled and labor intensive sectors. Future immigration policy makers can gain valuable insights from the effects of enacted legislation in order to minimize or forego the negative impacts of immigration on this important sector of the economy.

This article is based on the paper “The Impact of Immigration Enforcement on the U.S. Farming Sector,” which was published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics 96(1): 172-192.

Featured image credit: Alex E. Proimos (Creative Commons: BY-NC 2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1cpCyAg

_________________________________

Genti Kostandini- University of Georgia

Genti Kostandini- University of Georgia

Genti Kostandini is an Assistant Professor of Agricultural and Applied Economics in the College of Agriculture and Environmental Science at the University of Georgia. His research interests include regional economic development, risk and uncertainty in agricultural production, industrial organization, and agribusiness production and marketing.

Elton Mykerezi- University of Minnesota

Elton Mykerezi- University of Minnesota

Elton Mykerezi is an Associate Professor in the Department of Applied Economics at the University of Minnesota. His research interests include the study of human capital, causes of poverty, food insecurity and poor nutrition, the role of public assistance in enhancing household wellbeing, and rural business and labor market development.