In December, a federal judge ruled that the city of Detroit’s bankruptcy proceedings could continue, and it is now likely to take years for the city to settle its creditors’ claims. Gary Sands, Laura A. Reese, and Mark Skidmore look at Detroit’s recent history which has been characterized by deindustrialization and depopulation, and public mismanagement and corruption. They argue that even after the city’s bankruptcy is concluded, Detroit’s underlying fundamental structural weaknesses mean that its problems are unlikely to go away.

In December, a federal judge ruled that the city of Detroit’s bankruptcy proceedings could continue, and it is now likely to take years for the city to settle its creditors’ claims. Gary Sands, Laura A. Reese, and Mark Skidmore look at Detroit’s recent history which has been characterized by deindustrialization and depopulation, and public mismanagement and corruption. They argue that even after the city’s bankruptcy is concluded, Detroit’s underlying fundamental structural weaknesses mean that its problems are unlikely to go away.

The City of Detroit’s financial problems are widely recognized, especially after its bankruptcy was declared legal by a federal judge last December. But Detroit is not the only city facing a shrinking tax base, extravagantly underfunded pension liabilities and deteriorating public services. Other American cities have similar problems, but to a lesser degree. What sets Detroit apart, however, is the combination of extreme financial distress with a profound racial divide and poor public leadership.

Since 1950, the economic structure of Detroit has undergone extreme changes. The number of jobs in the city has fallen by 60 percent; manufacturing jobs by 93 percent. Despite the widely publicized relocation of some high tech and financial services jobs to downtown Detroit, employment in the city core has fallen by about 30 percent between 2000 and 2011. The aggregate value of real estate in Detroit declined by almost $6 billion (48 percent) since it peaked in 2006.

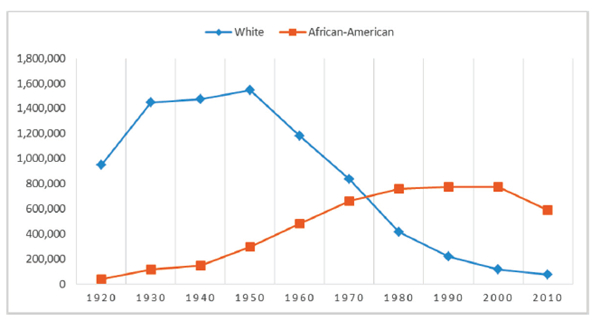

The number of Detroit residents has fallen by more than 60 percent since 1950; the non-Hispanic white population of the city declined from 1.5 million to 56,000, as Figure 1 illustrates. Detroit’s African-American population rose rapidly until 1990, when it too began to decline. Since the turn of the century, Detroit has lost four times as many black as white residents.

Figure 1 – City of Detroit racial trends, 1920–2010 (Population by Race).

Source: US Bureau of the Census.

During this same period, the suburban communities around Detroit remained predominantly white. Detroit has been at or near the top of lists of the most racially segregated US metropolitan areas for decades. The results of the most recent Census indicate that nearly three-quarters of African-Americans would have to leave the city to achieve racial balance across the metro area.

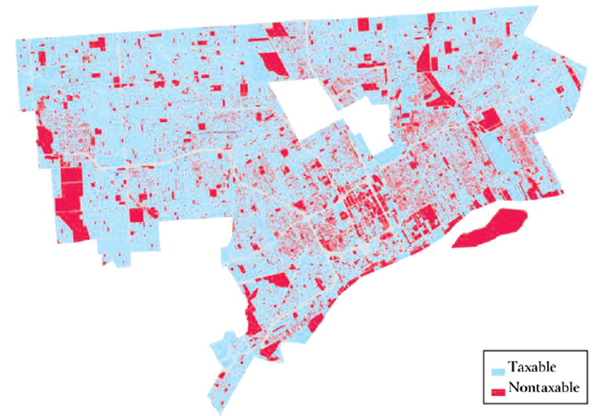

Declines in employment and population have left the city with expansive areas of vacant land and buildings, as Figure 2 shows. It has also meant that income and property tax collections have declined. Detroit residents and businesses face one of the highest tax burdens in Michigan, which has provided incentives for leaving the city. Despite Draconian cuts in public services, the City has incurred budget deficits in nine of the last eleven years.

Figure 2 – Taxable and non-taxable properties in Detroit

For the past for decades, Detroit has been forced to deal with these changes without a stable governing regime, an effective alliance of public and private sectors working for a common goal. For much of this period, Detroit has had a “vendor regime” in which government provides subsidies to private sector investments. The City’s redevelopment efforts – urban renewal, tax abatements and other subsidies – have benefitted private investors more than the public interest. When development occurs only with public subsidies, very little will happen when the City can no longer afford to provide incentives. This has, on occasion, contributed to instances of mismanagement and public corruption.

The bankruptcy proceedings promise to restore Detroit to financial viability, and bring recovery. The latter seems unlikely. Municipal bankruptcy is, first and foremost, about determining who will be repaid and how much they will receive. With total obligations in the neighbourhood of $20 billion and tens of thousands of creditors and pensioners, it is impossible to predict the final outcome with certainty. Some of the City’s debts will be restructured (repaid over a longer term at a lower interest rate), some (perhaps retiree health care costs) will be shifted to others and some will simply be defaulted.

The Detroit Future City report provides a framework for revitalizing neighborhoods and rationalizing public services. Yet, even if both of these efforts are successful, the 700,000 people who live in Detroit will still be overwhelmingly poor (59 percent of children and 42 percent of all Detroiters live in poverty), outside of the labor force (just 38 percent of the population over 16 is employed) and poorly educated (only 13 percent of Detroiters have a college degree; none of the schools within the city limits, either public or private, receive the top rating from Excellent Schools Detroit.

In time, bankruptcy may help to create some measure of investor confidence in the City. It will not, however, address the fundamental realities faced by a city that has few jobs and a work force that is often lacking in basic skills, let alone the ones necessary to succeed in the new economy. Even if new firms can be attracted to the city by cheap land and other incentives, they may provide limited direct benefits to Detroit residents. Bringing new jobs to Detroit is not the same as bringing new jobs to Detroiters.

Too little attention is currently being given to finding solutions to this constellation of problems. While the problems arising from concentrated poverty are perhaps the most intractable of all, they must nevertheless be dealt with. And there is a very long way to go.

It is expected that it will be at least 2 years, perhaps longer, before Detroit emerges from bankruptcy. It is virtually impossible to predict what the city will be going forward. There are a number of possible scenarios, none likely to be appealing, either to Detroiters or other Michigan residents:

- Municipal operations could be reduced to the barest essentials, including only the services that could be supported by a realistic budget that ensures the City is able to maintain fiscal balance.

- Many, even all, public sector functions of the residual Detroit could be taken over by other governmental entities, including newly-created local or regional authorities or by the county or state.

- Detroit could be dissolved as a municipal corporation with the more viable areas incorporating as smaller municipalities (The State of Michigan has recently used this approach to dissolve two small, insolvent public school districts). In some instances, the more viable areas might be annexed by adjacent suburban municipalities. The balance of the Detroit territory would revert to Wayne county control.

- The city becomes a de facto colony, with its resources exploited primarily for the benefit of others. This scenario has considerable currency among Detroiters, but it may be the least likely of the potential outcomes. In reality, for most suburbanites, Detroit offers little of value.

Will Detroit, as it goes forward, find a benign path to recovery, one that offers lessons for other aging Rust Belt cities? Or will the prevailing culture of racism, mistrust, and antipathy that exists in Southeast Michigan trump the efforts to address the financial and political issues? However Detroit’s future plays out over the next decade, there is no assurance that the city that emerges will be better off than today. But it will most certainly be different.

This article is based on the paper, Memo from Motown: is austerity here to stay? in the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1irjGc8

_________________________________

Gary Sands – Wayne State University

Gary Sands – Wayne State University

Gary Sands is an Emeritus Associate Professor of Urban Planning at Wayne State University. He has worked extensively with community-based organizations, local governments and private developers on various development issues.

_

Laura A. Reese – Michigan State University

Laura A. Reese – Michigan State University

Laura A. Reese is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Global Urban Studies Program at Michigan State University. Her main research and teaching areas are urban politics and public policy, economic development, and local governance and management in both Canada and the US.

Mark Skidmore – Michigan State University

Mark Skidmore – Michigan State University

Mark Skidmore is professor of economics at Michigan State University, where he holds the Morris Chair in State and Local Government Finance and Policy, with joint appointments in the department of agricultural, food and resource economics and the department of economics. His research has focused on public economics and urban/regional economics. His current research interests include state and local government tax policy, intergovernmental relations, the interrelationship between public sector decisions and economic activity, and the economics of natural disasters.