One of the widely accepted hurdles facing female candidates is navigating the fine line between seeming tough enough to hold office and appearing unfeminine and overly aggressive. Yanna Krupnikov and Nichole Bauer examine whether voters actually punish female candidates for being “too tough.” They find that voters’ opinions of candidates from their own party were unaffected by aggressive behavior, but that they judged female opposition candidates more harshly than their male counterparts for such conduct.

One of the widely accepted hurdles facing female candidates is navigating the fine line between seeming tough enough to hold office and appearing unfeminine and overly aggressive. Yanna Krupnikov and Nichole Bauer examine whether voters actually punish female candidates for being “too tough.” They find that voters’ opinions of candidates from their own party were unaffected by aggressive behavior, but that they judged female opposition candidates more harshly than their male counterparts for such conduct.

Every election cycle, more and more women run for political office and, post-election, a familiar narrative emerges about the campaigns that fail. The story usually goes like this: Voters don’t like weak politicians, so female candidates must show they are tough enough to hold office. But some of the losing female candidates “acted tough.” These women are labeled as overly aggressive, and voters don’t like aggressive female candidates. Female candidates end up balancing on a thin tightrope—be tough, but not too tough. Be feminine, but don’t be weak.

Take Linda McMahon’s 2010 Senate race in Connecticut; when McMahon lost, the Wall Street Journal speculated that it was her “tough” image—which emerged through a series of negative ads—that cost her the race. In a post-mortem of Meg Whitman’s failed gubernatorial campaign, the Washington Post concluded she got “tripped up by a Hillary-esque emphasis on being ‘tough enough.’” And, of course, there is Hillary Clinton, the quintessential example of the “tough enough” double standard.

This is a compelling narrative, but does this hold up to closer scrutiny? Put another way, do voters systematically punish female candidates for being “too tough”? We considered this question using a national study. Our study presented people with possibly the most extreme case of a candidate “acting tough”—attacking his or her opponent. What we found suggests that female candidates certainly could be punished for displaying too much aggression during a campaign, but only in very specific, limited cases.

There is certainly reason to believe that the “tough enough” double standard could limit female candidates. Psychology research shows that gender stereotypes suggest women should be more nurturing, gentle, and sympathetic compared to men. When people encounter women who don’t conform to this stereotype, they react negatively. Acting tough by attacking your opponent, being vocally critical, or even discussing national defense breaks with traditional stereotypes about women. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to suspect that people might not like female candidates who behave in this way.

But, psychology also tells us this story might be more complicated. People need to be motivated before they will use stereotypes to make a negative judgment. This motivation often comes if people already dislike the person in question. Conversely, people are unlikely to use stereotypes to judge a person they like. So, if a voter actually likes a female candidate to begin with, it won’t matter if she acts tough and breaks with gender stereotypes because the voter is not motivated to hold these breaks in gender stereotype against her.

We recruited 800 American adults to participate in a study that considers whether individuals actually punish tough and aggressive female candidates. We presented each participant with two candidates competing for a Senate seat. While in our full study we also consider same-gender races, here we focus on different-gender pairings. One set of participants were assigned to a simple control group where they merely learned the gender and party of the candidates, but were not told anything about the types of ads these candidates sponsored.

Another set of participants learned that both of the candidates aired negative ads, but one candidate was the instigator, meaning this candidate had “cast the first stone” and had gone negative first. The other candidate was the responder—meaning they merely responded to the initial attack. We randomly varied the gender of the instigator, sometimes a female candidate instigated, sometimes it was the male, and the party of the aggressor, sometimes it was a candidate of the participant’s own party who instigated, sometimes it was the other party’s candidate who went negative first.

This study lets us test the traditional media narrative that individuals do not like tough female candidates, or the alternative story we suggest. If the traditional media narrative is correct, the female candidate should suffer every time she goes negative regardless of her party or if she instigated the negativity. But, if the story is more complicated, then participants should only punish the female candidate if they do not like her. And, people should especially dislike an instigator of the opposing party.

We consider whether participants “punish” female candidates in based on their willingness to vote for her. One way to view punishment is to compare our participants’ thoughts about the candidate when he or she is the instigator of negativity versus when that same candidate is the responder.

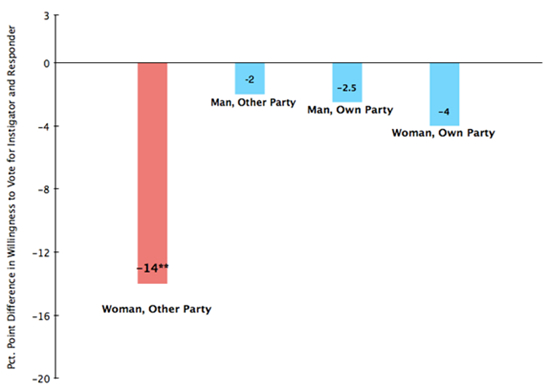

We use vote choice to show the level of punishment in Figure 1—the lower the bar, the fewer participants willing to vote for the instigator. We see some clear patterns. When the candidates are of the participants’ own party, it doesn’t matter whether they instigated or responded to negativity. Sure, people prefer it when the candidates don’t start the mudslinging, but when the candidate is of your own party the punishment is small and not statistically significant. What’s more, the candidate’s gender doesn’t matter: people treat both female and male candidates of their own party in the same way.

Figure 1: Level of Punishment for Instigating by Candidate Gender

It is only when the participant is evaluating a candidate of the opposite party that gender becomes pivotal. Participants dole out the harshest punishment to a female candidate of the opposing party. As the Figure 1 shows, the punishment for female instigators of the opposing party is the single largest effect in our results. What’s more, the participant’s party didn’t matter: Democrat participants harshly punished the Republican female candidate for instigating negativity and Republican participants harshly punished the Democrat female candidate for the same behavior.

Importantly, the participants are much more lenient toward the male candidate of the opposing party. Sure, they punish him when he instigates, but significantly less harshly than they punish the female candidate.

Are female candidates being punished because they broke with gender stereotypes? When we measure stereotype use, our results suggest that gender stereotypes do play a role, but only when participants didn’t like the way the female candidate behaved. In short, people were much more likely to focus on the fact that a female candidate broke gender stereotypes when that candidate was an instigator from the opposing party.

Put another way, our results suggest that voters are unlikely to punish a female candidate of their own party for, essentially, doing her job and trying to win an election for them. Although they may be may be more than happy to punish female instigators of the opposing party, people don’t have any motivation to worry that their own candidate is breaking with gender stereotypes and acting “too tough” even when she’s an instigator.

Negativity, of course, is only one example of “acting tough.” Nonetheless, our study—the results of which have been replicated with an additional experiment—suggests that there is a limitation to the media story of acting tough. Sure, some people might judge female candidates for “acting tough” but its unlikely they will punish their own beloved candidate for this type of campaigning. Returning to the McMahon 2010 campaign, perhaps it wasn’t that people disliked McMahon because of her negative ads, but that they judged her negative ads because they already didn’t like her. After all, McMahon took a “softer approach” in 2012 and she still lost.

This article is based on the paper ‘The Relationship Between Campaign Negativity, Gender and Campaign Context’ in Political Behavior.

Featured image credit: Aaron Webb (Creative Commons BY NC SA)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1g3nE8V

_________________________________

Yanna Krupnikov – Northwestern University

Yanna Krupnikov – Northwestern University

Yanna Krupnikov is currently an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Northwestern University. Her research focuses on political communication, campaign effects and political psychology. Her work has been published in the American Journal of Political Science, the Journal of Politics, Political Communication, Political Behavior as well as other peer reviewed journals. As of summer 2014, Krupnikov will be on faculty at Stony Brook University.

Nichole Bauer – Indiana University

Nichole Bauer – Indiana University

Nichole Bauer is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Indiana University. Her research examines gender stereotypes, campaigns, and voting behavior. Her work has been published in journals such as Political Behavior and Political Psychology.

Just a heads up, that is not a photo of Linda McMahon.

Thanks for letting us know – we’ve now corrected the image.

-USAPP Editor