Last year, the U.S. government shut down, and its debt ceiling was very nearly reached because of budget gridlock in Congress. When a budget agreement came, it was in the form of an ‘omnibus’ spending bill, which covered what would have otherwise been a number of appropriations bills. In new research, Peter Hanson finds that over the past 40 years, the Senate majority party has been able to exercise its power and shift towards this type of omnibus legislation in order to limit its exposure to difficult votes and ease the passage of the budget.

Last year, the U.S. government shut down, and its debt ceiling was very nearly reached because of budget gridlock in Congress. When a budget agreement came, it was in the form of an ‘omnibus’ spending bill, which covered what would have otherwise been a number of appropriations bills. In new research, Peter Hanson finds that over the past 40 years, the Senate majority party has been able to exercise its power and shift towards this type of omnibus legislation in order to limit its exposure to difficult votes and ease the passage of the budget.

The federal budget process in the United States is slowly collapsing, and the efforts of the Senate majority party to tame the unruly Senate floor are at least partially to blame. It is now routine for Congress to adopt the annual federal budget through massive “omnibus” spending bills that are thousands of pages long and worth hundreds of billions of dollars. These bills are widely disparaged because they are written behind closed doors in a way that minimizes transparency and accountability.

In recent research, I found that the shift toward omnibus legislation is partly due to the efforts of the Senate majority party to protect the reelection interests of its members. More broadly, I reach two conclusions about the nature of majority party power in the Senate. First, the Senate majority party has a greater ability to shape legislative outcomes than is typically recognized. Second, the majority party is likely to exercise this power when it is weak and has difficulty controlling the Senate floor.

There is a vigorous debate among scholars about the strength of parties in Congress. American congressional parties are weak compared to their counterparts in parliamentary systems. Party leaders have few tools to pressure members to vote with their party, and members’ voting decisions are more likely to reflect their own judgments about how best to win reelection than the preferences of their leaders. Most scholars have concluded that the majority party is especially weak in the United States Senate. The rules of the Senate permit unlimited debate on any issue and allow members to offer amendments on any topic. The combined effect of these rules is that decisions are made through negotiation and a process of debate and amendment on the Senate floor rather than dictated by the majority party.

I looked at the majority party’s management of the annual appropriations process over nearly four decades. The findings show how the majority party manipulates this process and creates omnibus bills to shield it from politically damaging votes and to ease the passage of a budget.

The Senate’s traditional way to fund the government is to adopt a dozen appropriations bills covering different topics like agriculture or defense in the “regular order.” The regular order is a set of routine procedures in which spending bills are written in committee, brought to the floor individually for debate and amendment, and adopted. Policymakers I interviewed for the study say that members prefer the regular order because it gives them the opportunity to amend bills, claim credit for accomplishments, and take public positions on issues.

The regular order has a downside. The minority can take advantage of the Senate’s open rules to force votes on amendments that may cause political harm to members of the majority. Bills can also become trapped in gridlock if they are too controversial, threatening the majority party’s reputation if it cannot pass a budget. These problems are particularly likely when the majority party is weak because it has a small margin of control, is ideologically divided or ideologically distant from the minority.

The majority party’s solution is to take two steps that limit its exposure to difficult votes and ensure the passage of the budget. First, it abandons the regular order by opting not to bring individual bills to the floor for debate and a vote. In the words of one long-time congressional staff member, “there are 70 senators who are basically disenfranchised” when the majority party takes this step for the obvious reason that senators cannot debate legislation that is never brought to the floor. The Senate failed to give an individual vote to 26 percent of all appropriations bills between 1975 and 2012.

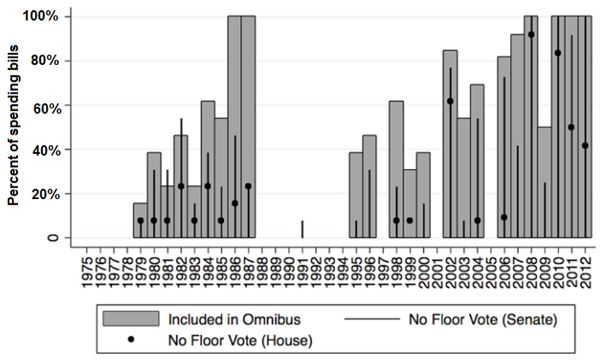

Second, it combines some or all of the dozen annual spending bills into a massive “omnibus” package. Omnibus bills overcome gridlock because they create a broad coalition of support for the budget by combining spending on controversial matters like social programs with more popular spending on matters like defense. In the years I studied, 39 percent of all appropriations bills were included in an omnibus package, including virtually all bills in recent years, as Figure 1 illustrates.

Figure 1 – Consideration of annual appropriations bills: U.S. Congress, 1975–2012

An additional consequence of omnibus bills is that they offer fewer opportunities to debate and amend legislation than would otherwise occur in the regular order – a feature useful to a majority party seeking to escape difficult votes. Former Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle states that omnibus bills “limit your access to correcting amendments, and so [they] are viewed by most senators as a sort of double-edged sword.” Policymakers say this is because omnibus packages are large, unwieldy, and often brought to the floor late in the year when funding for the government is about to expire. My analysis shows that debating an omnibus package instead of debating all bills in the regular order reduces the number of roll call votes on amendments to just 29 percent of the usual level.

These findings show that the decision to adopt bills in the regular order versus in an omnibus package is not one of legislative style over substance. It is a way of wielding power. Senate leaders cannily manipulate the way in which legislation is brought to the floor to build a coalition to pass the budget and to limit the opportunity for members to offer amendments.

Standard tools of statistical analysis show the majority party is more likely to abandon the regular order when it is weak and has difficulty controlling the floor. The benefit of adopting omnibus bills is that they allow the Senate to muddle through difficult times, pass a budget, and avoid a government shutdown. The downside is that these tactics have eroded the once admired process for adopting the federal budget and led to the creation of an ad-hoc system that is not transparent and is disparaged by Democrats and Republicans alike.

Featured image credit: chbrenchley (Creative Commons BY NC SA)

This article is based on the paper, ‘Abandoning the Regular Order: Majority Party Influence on Appropriations in the U.S. Senate’ in Political Research Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1lkqnur

_________________________________________

Peter Hanson – University of Denver

Peter Hanson – University of Denver

Peter Hanson is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Denver. His fields of interest include the U.S. Congress and how it functions when parties become polarized. He also helped to design and carry out the University of Denver’s first Colorado Voter Poll in the 2012 presidential election. He worked as a legislative assistant in the office of Senate Democratic leader Tom Daschle from 1996-2002, and in the office of U.S. Rep. Stephanie Herseth-Sandlin in 2004.