A common saying is that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, but is this true in politics as in life? In a new study, Anthony Fowler and Michele Margolis look at the effects of increasing voters’ political knowledge on their support for the Republican and Democratic parties. They find that because those with progressive views are less likely to know where parties stand, providing people with information about parties’ positions will increase support for the Democratic Party by as much as 15 percent.

A common saying is that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, but is this true in politics as in life? In a new study, Anthony Fowler and Michele Margolis look at the effects of increasing voters’ political knowledge on their support for the Republican and Democratic parties. They find that because those with progressive views are less likely to know where parties stand, providing people with information about parties’ positions will increase support for the Democratic Party by as much as 15 percent.

Scholars and pundits frequently bemoan American voters’ lack of political knowledge, perhaps for good reason. If voters do not know where the major parties stand on important issues, how can they translate their policy preferences into vote choices? How can they influence policy or hold their elected officials accountable? In recent research we ask what would happen if the electorate were better informed. How would public opinion, election results, or policy change? Would one party benefit from a more informed electorate? We find that when individuals acquire more political knowledge, their attitudes shift towards the Democratic Party.

Some have argued that the lack of information has no systematic effects, because uninformed voters can rely upon what political scientists call “informational shortcuts.” These shortcuts, such as party labels and endorsements, help voters to quickly identify the candidate they would likely vote for if they were better informed. Even when these shortcuts fail, scholars have claimed that neither party routinely benefits because mistakes on both sides cancel out. Meanwhile, building on the well-established finding that high-information voters tend to be more conservative, others have claimed that a better-informed electorate would therefore offer greater support to conservative candidates. Our study contends that these views are incorrect. We expect a better-informed electorate to benefit the Democratic Party in the U.S., because those with liberal views who would likely align with the Democrats if they were informed are also the least likely to know the parties’ ideological positions. Therefore, voting “mistakes” probably do not cancel out. Rather, they should systematically hurt Democratic candidates.

To illustrate, consider public opinion and knowledge about the capital gains tax. According to our surveys, 45 percent of Americans do not know which major party is more supportive of raising capital gains tax, despite most holding an opinion on the issue. Of those who know the parties’ positions, 58 percent believe that capital gains should be taxed at the same rate as regular income—or higher. Of those who do not know the positions of the parties, 77 percent hold this view. In other words, those with progressive views are less likely to know where the parties stand and less able to accurately translate their opinions on tax policy into a vote choice. One possibility is that in acquiring information about the parties’ stances, citizens become more conservative. However, more plausibly, well-informed citizens differ from their less informed counterparts on a number of dimensions, including political attitudes.

To provide evidence for our claim, we randomly provided citizens with political information and tested whether this information affected partisan attitudes. In particular, we informed individuals about the positions of the major political parties on important issues and tested whether they subsequently changed their attitudes toward the parties. We conducted two experiments that differed significantly in many ways, including the samples, issues discussed, and how the information was provided. Nonetheless, both experiments yielded nearly identical results.

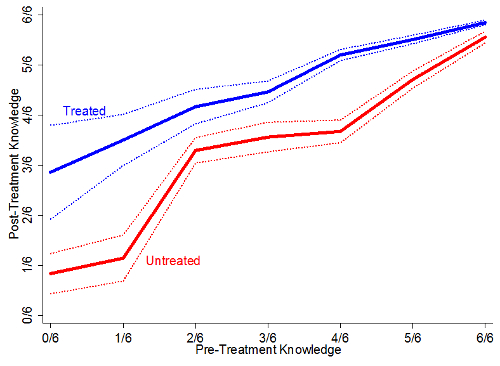

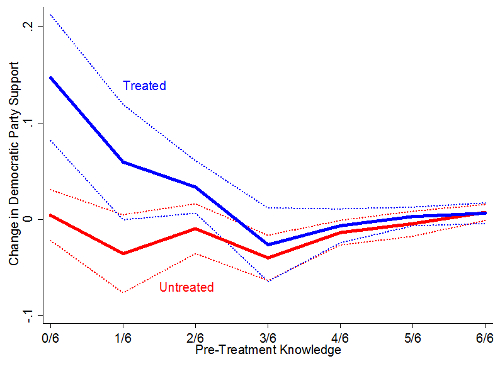

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate our results from one of the experiments, in which we informed respondents about six policy issues: abortion, gay marriage, gays in the military, the minimum wage, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and unemployment insurance. We found that survey respondents retained the information given to them, as evident in Figure 1. Treated respondents—that is, those who received political information, who are depicted by the blue line—had higher levels of political knowledge than those who did not receive any information, depicted in red. More importantly, as Figure 2 shows, informing voters about the parties’ positions significantly shifted public opinion in favor of the Democratic Party and away from the Republican Party. These effects were strongest for those who started with the lowest levels of information, those least likely to be able to connect their policy preferences to the correct party. Differences do not appear for those who were already fully informed, who were presumably already able to translate their policy preferences into a party preference.

Figure 1 – Effect of Treatment on Political Knowledge

Figure 2 – Effect of Treatment on Partisan Attitudes

In many respects, our findings are unsurprising. Many lower-income citizens align with the Democratic Party on questions of economic policy; however, because they also tend to pay little attention to politics and do not know the parties’ positions, casting an informed ballot is difficult. When these individuals acquire more political knowledge, their partisan attitudes systematically shift as they are better able to identify which party better represents their policy preferences. The size of this effect is striking. The effect of providing information to the previously uninformed—shown on the left side of Figure 2—produced an attitude shift toward the Democratic Party representing 15 percent of the scale measuring partisan attitudes. A shift of this magnitude is comparable to the average difference between Republicans’ and Independents’ party evaluations or between those of Democrats and Independents.

Our results suggest that a more informed electorate could significantly shape politics by changing public opinion, and by extension, influencing election results and ultimately public policy. Further, previously under-represented citizens, newly armed with political knowledge, could encourage government to act on their preferences and achieve policy outcomes more consistent with the views of the electorate as a whole.

Featured image credit: DonkeyHotey (Creative Commons BY)

This article is based on the paper, ‘The political consequences of uninformed voters’, in Electoral Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1nr6W3N

_________________________________________

Anthony Fowler – University of Chicago

Anthony Fowler – University of Chicago

Anthony Fowler is an Assistant Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy Studies at the University of Chicago. He studies political representation, with particular interests in elections and participation. His work has recently appeared in the American Journal of Political Science, Journal of Politics, and Quarterly Journal of Political Science.

Michele Margolis – Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Michele Margolis – Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Michele Margolis is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Later this year, she will join the Political Science Department at the University of Pennsylvania as an Assistant Professor. She studies public opinion, political psychology, and religion and politics. Her research has appeared in the American Journal of Political Science and Electoral Studies, and her current book project is titled Religion and Politics: A Two-Way Street.